Samuel B. Watrous was a rancher, farmer, and trader in Mora County, New Mexico, after whom the town of Watrous is named.

Born in Montpelier, Vermont, in 1809 to Erastus Watrous and Nancy Bowman, Samuel was baptized Erastus but later changed his name. Orphaned while still young, he was sent to live with an uncle. At 26, he joined a wagon train and headed for Taos, New Mexico.

Upon his arrival, he began clerking at a store, and within two years, he was the father of a young son named Joseph. The mother was Tomacita Crespin, but rumors abounded that the boy was not Samuel’s and that she was already pregnant when they married. However, Samuel raised the boy as his own, and the couple would have six more children: Mary Antonette, Emeteria, Louisa, Abelina, Samuel, Jr., and María Antonia.

By 1839, he, Tomacita, and their small son were living in the mining camps of the Ortiz Mountains, just south of Santa Fe. Not a miner, Watrous supplied miners with goods he purchased from Taos merchant Charles Bent and traded in deerskins.

Watrous was successful as a mining merchant. In the late 1840s, he purchased a one-seventh interest in the Scolly Mexican land grant and moved his family to La Junta, New Mexico (then still a province of Mexico). Though the area had long been the favorite hunting grounds of several Plains Tribes, including the Comanche, Kiowa, Apache, and Ute, who were none too fond of settlers encroaching upon their lands, Watrous was seemingly unafraid.

Immediately, he began work on a sizeable fort-like adobe home at the junction of the Mora and Sapello Rivers. The hacienda-style home included 20 rooms, all opening onto an enclosed courtyard. At one end was a large store, and in the back, two large storerooms. In addition to rooms for the family, others included a drying room, storage for farm implements, a granary, and a room where various crafts were made. At the back were the servants’ quarters. A wagon from St. Louis, Missouri, brought lumber and luxury goods, including a piano, heavy marble-topped wooden furniture, china dinner sets, gilded clocks and mirrors, and books. More materials were imported from Mexico, including blankets and clay pots.

To provide shade for the home, he transported cottonwood trees from the east side of the Canadian River, exported fruit tree seedlings from Missouri, and even made a trip back east for willow sprouts. He often told family and servants, “Come now, we will plant more trees.” He also developed farmland, including hops, alfalfa, bluegrass, and vegetables. By the time his home was completely built, it was self-contained.

Today, the Watrous Valley Ranch owners, located at 2286 Hwy 161 in Watrous, still use the Samuel B. Watrous Ranch House and Store. The ranch includes the carefully restored Watrous House and thousands of acres of original grazing land.

Employees of the Watrous family included overseers, herdsmen, hunters, housemaids, nursemaids, and cooks. Many women would gather plants from spring until fall to be used as foods, condiments, and medicines. Life in the household was one of New England’s discipline and Spanish ease, where the women and children, family and employees, mingled.

Over the years, Watrous amassed large herds of cattle and ample grazing land just north of the Mora River. He sold and traded what his ranch produced with residents, travelers along the Santa Fe Trail, and, later, to troops at nearby Fort Union. In 1847, Watrous hired the Tipton brothers, William and Enoch, whom he knew during his days in the Ortiz Mountains, to help him claim and settle his portion of the Scolly Grant. The Tiptons settled what would be called Tiptonville on the Mora River, a few miles northwest of La Junta.

In 1849, Samuel’s daughter, Mary, who was only 12, married her father’s partner, William Tipton. At that time, Tipton became a partner in Watrous and Tipton. Together, they owned 20 freight wagons that hauled merchandise for many years on the Santa Fe Trail between Missouri and New Mexico.

By then, New Mexico had become a territory of the United States. More and more settlers came to the area, taking over the traditional hunting grounds of the Moache Ute, Jicarilla Apache, Kiowa, and Comanche. Due to the increased traffic on the Santa Fe Trail, more and more emigrants, and their game being reduced, friction between the Indians and new settlers flared. Troops were soon sent in to protect the citizens of the territory.

When Lieutenant Colonel Edwin V. Sumner came into command in 1851, he found the military encampments in deplorable conditions. He immediately disbanded these temporary posts, relocating the troops to posts closer to the Indians. That year, he also began work on establishing Fort Union, about nine miles northwest of La Junta on the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail.

The new fort became the principal depot for supplies for other forts in the region, utilizing the fertile Mora Valley ranchers and farmers, including Samuel Watrous, as suppliers. Because of the numerous military trails that joined at La Junta, hundreds of ox and mule teams, freighters, muleteers, drivers, escorts, and travelers passed yearly by the Watrous Store, which prospered greatly.

What was left of Fort Bascom in 1907. Over the next century, the old post continued to deteriorate, and today, nothing is left.

Samuel had to rapidly increase his herds to keep up with the demand for beef. He established a second ranch on the Canadian River, about eleven miles from old Fort Bascom, near Tucumcari, New Mexico. After the ranch houses and the corrals were built and stocked, Watrous returned to La Junta to visit his family. Unfortunately, while he was away, a Comanche war party raided the ranch, killed the overseer, and drove off the rest of the men. They then took all the stock, including cattle, mules, oxen, and a year’s provisions. When they obtained all they wanted, they burned the rest of the buildings and belongings, including five freight wagons and farm implements.

Later that year, another raid, this time by Apache warriors, was made on his La Junta ranch. After capturing the herders and stealing about 45 horses, they fled. Fort Union troops trailed them but were unsuccessful in capturing or regaining the horse.

Watrous understood there was only one way to end the attacks. He soon visited Washington, D.C., to ask the Indian agency to move the Plains tribes to a more suitable place because there was not enough game left for them to live on. His request was ignored.

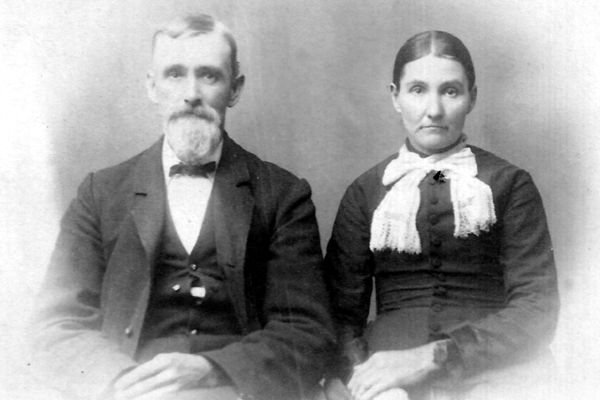

Samuel Watrous and his third wife, Josephine Chapin Watrous.

So, Samuel took another tactic and began to feed any Indians who came to his ranch. All were made to feel welcome, and before long, people came down from the mountain hamlets and were fed and befriended. One day, they came with news that a stranger, they called the “Solitary One,” was living among them. They said he was a holy man who had come to them to preach, heal, and perform miracles from his cave on the rock peak of Rincon de Tecolote. Interested in their tale, Watrous wanted to meet this stranger, and he soon trekked up the mountain.

The “Solitary One” is known in history today as the Hermit of La Cueva. An Italian noble and missionary named Juan Maria Agostiniani had traveled the world for over three decades before joining a caravan in Council Grove, Kansas, and walking with them to Las Vegas, New Mexico. He was a deeply profound, deep thinker and extremely remarkable conversationalist. Watrous enjoyed being with him, hearing his tales, and exchanging ideas. For years, he visited with the old hermit until, one day, the old man was found murdered. His killer was never found.

Samuel’s first wife, Tomasita, died in 1857. He remained single with his children for several years until about 1864, when he married Rosaline D. Chapin. The marriage, however, was brief, as Rosa died in childbirth. Samuel then married Rosa’s sister, Josephine, with whom he had two more children—Rosa and Charles Watrous.

Watrous and Son’s store was among the most important on the Santa Fe Trail. He and his son-in-law, William Tipton, had a contract to supply beef to Fort Union, with about 600 men garrisoned there at the time. Scarcely, a day passed, and travelers did not go by the Watrous house. These travelers differed from the early trappers and freighters, with wagons loaded with household furnishings, chicken crates tied on the back, and a straggling milk cow in the rear. Men rode on horseback beside their cattle-yoked wagons, and from within the wagons, women and children peered out with wary curiosity. In the 1850s, the heaviest travel had gone by way of the Cimarron Cutoff, for the Raton Pass had proved as great a peril to the cumbersome wagons. However, that changed when “Uncle Dick” Wootton built his toll road in 1865.

Watrous grazed over a thousand heads of livestock, cattle, and horses, eventually luring cattle rustlers to La Junta. By the 1860s, the Coe Gang hid in Dog Canyon about eight miles northeast of La Junta. For several years, these men earned their livelihood raiding ranches and military installations from Fort Union, New Mexico, to the south, Taos, New Mexico, to the west, and as far north as Denver, Colorado. They also preyed on freight caravans traveling along the Santa Fe Trail and area ranches. Eventually, William Coe was captured near Shoemaker, New Mexico, escaped, was hunted down again, and hanged in Pueblo, Colorado, in 1868.

In addition to ranching, Samuel and his partners built a woolen mill at Cherry Valley, some eight miles northeast of La Junta. The New Mexico Woolen Enterprises Manufacturing Company, including a three-story stone building, adobe living quarters for the workmen, storerooms, corrals, and stables, was in full operation by 1867. For the next 20 years, the mill would produce blankets, rugs, carpets, and serapes. In the end, however, due to disagreements among his sons and sons-in-law, Samuel ceased operations in 1884.

Numerous small ranches grew up in the valley. Soon, the Indian menace had been subdued, and there was a rumor of disbanding the forts. Watrous could see that would mean a decline, so he turned his attention to planting orchards and farming.

By this time, many of Watrous’s children were married. His sons, Joseph and Samuel, Jr, and his son-in-law, William Tipton, were his business partners. William Kroenig, who had married Maria Louisa Watrous, discovered copper on Baldy Mountain and had a ranch adjoining the Watrous property. Two other Watrous daughters, Belina and Emeteria, married entrepreneurs. Carl Wildenstein, an Austrian designer, and civil engineer, married Belina, and George Gregg, the proprietor of Gregg’s Tavern, a stage stop on the Barlow and Sanderson line, wedded Emeteria. María Antonia married James Johnson, the first Anglo settler at Cherry Valley, later called Shoemaker.

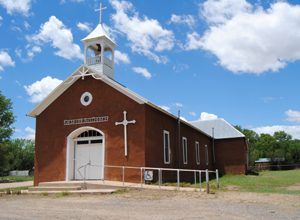

By 1879, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad planned to barrel through La Junta, and Samuel Watrous donated ten acres for the right of way, stations, and yards. When the official townsite was laid out a few years later, the settlement was renamed Watrous. Though the railroad caused the traffic on the Santa Fe Trail and the stage lines to cease, the town of Watrous became a vital shipping point for local products. Fort Union used it to transport supplies and personnel until its abandonment in 1891. The town boasted numerous saloons, businesses, and a school by then.

Samuel Watrous died of two gunshots to the head at the age of 77. Though the official documents stated that he had committed suicide by shooting himself twice in the head, that didn’t make sense to some folks.

The Death of Samuel B. Watrous Remains an Unresolved Mystery, Las Vegas Daily Optic, Marcy 17, 1886:

A special dispatch to the Daily Optic this morning from Watrous gives the startling intelligence that S B Watrous, senior of that town, committed suicide this morning at his residence in the suburbs of that place by shooting himself’ twice through the head with a revolver. The people in Watrous were greatly shocked to learn of the terrible death of the venerable pioneer, and what his motive was for committing the rash act is merely a matter of conjecture… It is understood he leaves a fine estate to his heirs.

On the same date, the Santa Fe Daily New Mexican added a few details:

S: B. Watrous, Sr. Goes To His Death Under Peculiar Circumstances

S. B. Watrous, Sr. committed suicide at Watrous station this morning at 5 o’clock by shooting himself through the head twice with the same weapon used by his son [Samuel Jr.], who killed himself a few months ago, and since which time the father has been greatly troubled.

Later, however, family members related other, more sinister, possibilities. James E. Romero, Jr., a great-great-grandson of Samuel and Tomacita Watrous related that family tradition alleged that Joseph Watrous and Josephine Chapin Watrous (Samuel’s last wife) became jealous of Samuel, Jr. and plotted his death. Further, Romero alleged that Joseph killed the younger Watrous on the road to Shoemaker, New Mexico. He went on to say that the senior Samuel was highly distraught, would not accept that his son had killed himself, and, in time, became suspicious and accused Joseph and Josephine of killing his son. An argument then erupted, which was overheard by the servants, and shots were heard. When the servants entered the living room, Samuel lay dead with two bullet wounds in his head.

In a letter to the editor of the New Mexico Magazine, another descendant — Angeline Guerin Kramer, claimed that her grandmother, Belina Watrous, told her that Samuel, Jr. had been murdered because he was his father’s principal heir and that his stepmother, Josephine Chapin Watrous, had a hand in the murder. However, an accomplice had shot him. She also stated that Samuel Watrous was possibly killed in self-defense by his wife Josephine during a violent domestic fight. In her letter, she also made another critical point — how she asked, could someone shoot himself twice in the head?

After a long and successful life, Samuel B. Watrous was buried next to his wives in unmarked graves in the small cemetery just over the hill East of his home. Leaving no will after his death, there were complications in settling the estate due to questionable titles of the Scolly Land Grant and the complicated division among many heirs. The family was in turmoil, and it was reported that Josephine Chapin Watrous never spoke again to any of Samuel’s children other than Joseph, the allegedly adopted son of Samuel, and her children, Charles and Rose.

The village of Watrous continued to thrive after the death of its namesake for several years.

Today, this small town of just about 135 people is a National Historic Landmark District that includes the routes of the Santa Fe Trail that initially came together in the La Junta area and buildings and structures associated with the community’s active use from 1835 to 1879. Much of La Junta’s original character and integrity remain today, from its rustic built environment to the natural beauty of the rangeland in the valley. Deep trail impressions and wagon wheel ruts throughout the district still dot the landscape.

The Watrous Valley Ranch and House passed through three other families before coming into the hands of the current owners, who have completely restored the house. Located at 2286 Hwy 161, the ranch still has thousands of acres of original grazing land and hundreds of Samuel Watrous‘ original Black Willow and Cottonwood Trees.

Watrous is about 16 miles northeast of Las Vegas, just over the county line in Mora County.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

Also See:

Santa Fe Trail – Highway To the Southwest

Santa Fe Trail Through New Mexico

New Mexico – Land of Enchantment

Watrous – River Junction on the Santa Fe Trail

Sources:

Ancestry.com

Clark, Anna Nolan, Fifty Years of Change, New Mexico Magazine, February 1938

New Mexico Office of the State Historian

Santa Fe Trail Association Quarterly, Volume 12, February 1998

Santa Fe Trail Site Map & Writing Credits

Varney, Philip; New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns: A Practical Guide; University of New Mexico Press, 1987