Off the Path – El Rancho de los Golondrinas

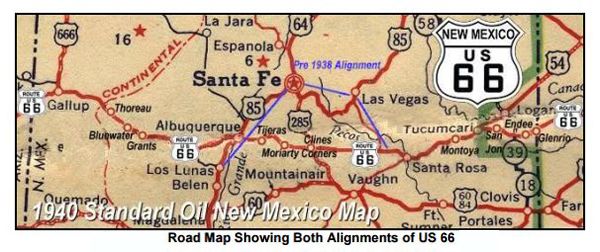

During the early years of the federal highway system, the realignment of highways was commonplace as engineers sought to create safer and more efficient roadways. Many realignments tended to be minor; a few involved a significant highway re-routing. Such was the case with Route 66, which passed through New Mexico. Approximately 507 miles long in 1926, the alignment of Route 66 in the state was reduced to 399 miles by 1937. The longest sections of the initial alignment created a large S curve as the road stretched across the state’s middle. West of Santa Rosa, it turned north, crossing nearly 20 miles of empty rolling plains before crossing the Pecos River near the 19th-century Hispanic communities around Dilia.

Route 66 continued north an additional 25 miles, passing through a series of small ranching settlements before intersecting with I-25 at Romeroville southwest of Las Vegas. Aligning with I-25, Route 66 followed the corridor of the old Santa Fe Trail and its successor, the Santa Fe Railroad, and passed through Pecos River Valley and the villages of Tecolote, Bernal, San Jose, Rowe, and Pecos. The highway then climbed Glorieta Pass and descended the narrow defile at Cañoncito, where it diverged from the railroad alignment to veer toward Santa Fe.

La Fonda Hotel Today.

Route 66 entered the state capital along College Street (now Old Santa Fe Trail), then turned west on Water Street at the rear of the La Fonda Hotel. It exited downtown Santa Fe along Galisteo Street and turned south upon connecting with Cerrillos Street. Climbing the gentle north slope of La Bajada Mesa, the highway descended the mesa’s sharp south escarpment along a series of hairpin turns before arriving at the village of La Bajada.

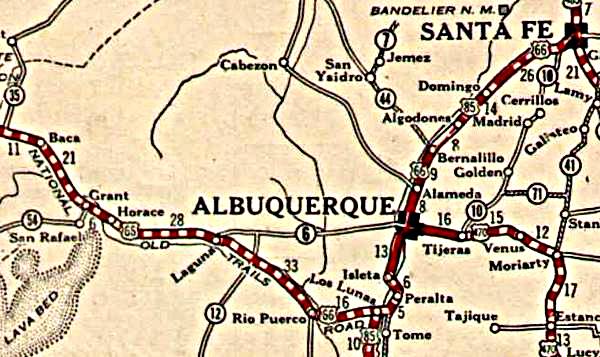

Once again aligning with the railroad just north of Domingo Station, Route 66 roughly paralleled the tracks to the east as it meandered through the Sandia Mountains before arriving at Bernalillo. There, it closely paralleled the railroad and entered Albuquerque along Fourth Street.

From this point, the highway crossed the Rio Grande three times: first at the Barelas Bridge, then at Isleta Pueblo, and ultimately at Los Lunas. Heading west, Route 66 paralleled the railroad as it climbed the western escarpment of the Rio Grande Valley and curved northwest toward Correo and the Laguna Pueblo. There, it resumed its westward course, crossing the Continental Divide and then paralleling the railroad as it descended the valley of the Puerco River toward Gallup, New Mexico, and the Arizona border.

La Bajada Road in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

While the corridor along which this Route 66 alignment passed for 11 years is readily traceable along Interstate 25 and federal and state highways, few sections of the historic roadway remain, especially in rural areas. Given the Bureau of Public RRoad’spolicy of “staged construction,” in which various sections of roads within the federal highway system were gradually upgraded rather than a single highway being completed end to end, some of the pre-1937 sections of Route 66 were never improved beyond receiving an initial gravel surface. For example, the road from west of Santa Rosa to Romeroville and much of the road west to Santa Fe was never a hard-surfaced road during its tenure as Route 66. Nor was the road at La Bajada ever a hard surface road until it was realigned three miles to the east in 1932, approximating the current alignment of Interstate 25.

Although Route 66 south of Albuquerque to Los Lunas was paved by 1926, it was realigned along the west bank of the Rio Grande five years later to remove the two additional river crossings below the Barelas Bridge. Thus, while a review of records for most of these road sections suggests that it is possible to trace many of the approximate pre-1937 alignments of Route 66, most current roads do not represent the historic dirt and gravel highway. The most intact sections with the highest degree of alignment integrity are those that pass through the village of Pecos, which was never hard-surfaced during its tenure as Route 66, the roadway at the La Bajada escarpment, and the section extending from near Algodones south across the Sandia Reservation to North Fourth Street. Short road sections, some now on private lands, may also offer examples of the historic roadway.

1927 Albuquerque Map

In contrast, urban road sections traversed by Route 66, such as College, Water, and Galisteo Streets in Santa Fe and Fourth Street and Isleta Boulevard in Albuquerque, were paved during their service to the highway. Over the more than seven decades since Route 66 was realigned to other roadways, these streets have remained largely unaltered, their current surfaces and curbing indicative of standard improvements characteristic of all urban streets. While their commercial roadsides have developed substantially, some buildings lining these streets and associated with automobile tourism before 1937 remain. In Santa Fe, many building histories indicate that all the remaining buildings associated with automobile tourism have undergone substantial alterations. In Albuquerque, three early tourist courts, two gas stations, and a cafe remain. The gas stations and cafe are listed as contributing resources within the Barelas-South Fourth Street Historic District. The ” mushroom Kiosk” on Isleta Boulevard is also listed in the State Register of Cultural Properties.

Precursors to the pre-1937 alignments of Route 66 in New Mexico were the Texas-New Mexico Mountain Highway and an arm of the multi-branched Ozark Trail extending from the Texas border at Glenrio to Santa Rosa and then northwest to Las Vegas. Similarly, the National Old Trails Highway, an alignment included in the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway, followed the Santa Fe Trail into the northwest corner of the state at Raton, extended to Santa Fe, then stretched south to Los Lunas and west to Gallup.

Route 66 Sign in Algodones, New Mexico

During its early years, the pre-1937 alignment of Route 66 offered motorists highway sections that represented some of the best and worst of the New Mexican roads within the federal system. The Automobile Blue Book described the section between Santa Rosa and Romeroville as “travel, sandy dirt, and stone, some of which is poor.” Still, it acknowledged that pavement extended north from Isleta to Algodones and, by 1928, to Santa Fe. Similarly, it described the road from Los Lunas to Gallup as “gravel and dirt.” While very little of New Mexico’s highway mileage was paved in the 1920s, the discrepancies apparent along Route 66 reflect the various priorities of the state highway department and the state’s decisions in utilizing federal monies it received to complete its share of the roads that were included within the federal road system.

Since priorities were often given to more heavily used roads, lesser-used roads, such as those from Santa Rosa to Romeroville, tended to receive less improvement funding. Annual traffic counts conducted by the highway department extending over the 11 years of the pre-1937 alignment show that Route 66 never carried the number of vehicles that traveled on U.S. 85. As a result, the section from Santa Rosa to Romeroville and the section west from Los Lunas to Laguna received relatively few improvements. In contrast, the section from east of Santa Fe to Los Lunas, which carried traffic through the state capital and the Rio Grande Valley, received many of the early paving projects left by the highway department.

Rio Puerco Bridge, New Mexico.

Although the state lacked the funds to improve roads that were not eligible for federal funding, some motorists began using the trace west from Santa Rosa, especially during good weather. Termed “the Santa Rosa cut-off,” the new road siphoned traffic away from the Route 66 alignment, further reducing the number of cars using the highway and, as a result, weakening the priority that had emphasized improvements to the road north from Santa Rosa to Romeroville. A similar development occurred west of Albuquerque when the city’s boosters, led by ex-officio mayor Clyde Tingley, advocated the creation of an improved road running directly west of the city. With the completion of a bridge across the Rio Grande just west of Old Town in 1931 and the funding of a through truss bridge across the Rio Puerco (completed in 1933), this new route, termed “the Laguna cut-off,” also served to reduce traffic along the Route 66 alignment from Los Lunas to the Laguna Reservation.

As a result of these increasingly aggressive lobbying efforts to realign Route 66 directly west across New Mexico, by the early 1930s, even engineers for the Bureau of Public Roads were studying the possibility of realigning Route 66. Usually loathe to approve federal funding for new roadways if they were seen as duplicating previously funded projects, they saw the value of a more direct route across the state. Despite protestations from supporters of the original route, especially boosters in Santa Fe, by 1932, the Bureau of Public Roads had accepted the request of the State Highway Commission to realign Route 66 in the future. Completing the new bridge across the Rio Puerco in 1933 opened the way for realignment. When the last sections of hard surfacing were completed in 1937, the shorter east-west alignment replaced the original alignment. This realignment was accompanied by several other shorter realignments, especially in the western part of the state, as several railroad grade crossings were eliminated by realigning Route 66 south of the Santa Fe line from Grants to Mentmore west of Gallup.

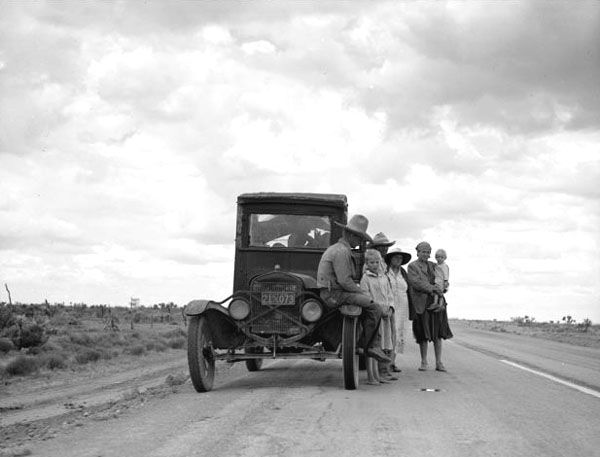

Automobile travelers in New Mexico during the Great Depression.

The inventory of these pre-1937 alignments and their associated roadside properties offers a sense of the comparative rate of development that occurred along Route 66 during the road’s first and second decades. The pioneering era of private automobile travel, which extended into the Great Depression, was marked by a concentration of motorist services in the population centers along the road. While records denoting roadside services during that era are few, most indicate the garages, hotels, cafes, and other services located in larger towns with isolated rural services. In contrast, by the 1940s, several gas stations, cafes, and even tourist courts had begun to appear along rural sections of the realigned highway, giving rise to the perception of Route 66 as a linear community sustaining travelers and residents who drew their livelihood from the road. As a result, those few remaining properties identified with the pre-1937 alignment of Route 66 tended to appear in populated areas such as Bernalillo, Los Lunas, Santa Fe, and Albuquerque.

The primary significance of Route 66’s pre-1937 alignment in New Mexico lies in how it reflects the early federal highway system’s use of existing movement patterns across the land. Historically, New Mexico’s Primary Location had been north and south, with patterns determined by routes that followed the Rio Grande and Pecos Valleys and relied upon infrequent mountain passes for latitudinal movement.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2024.

Also See:

New Mexico Route 66 Photo Gallery

Route 66 in the Pecos River Valley

Source: National Park Service