Gardiner was the second coal-mining town after Blossburg. It was established in Dillon Canyon on the vast Vermejo Park Ranch in northeast New Mexico, about three miles southwest of Raton, New Mexico.

Some earlier prospecting and individual selling of coal occurred in the area before the official “initial discovery” in 1881. At that time, Santa Fe Railroad geologist James T. Gardiner found large coal deposits only a few miles west of Raton’s main Santa Fe Railroad line. The town was named for him, and mining operations began in 1882.

The Old Gardiner Mine, or Blossburg #4, as it was called, began production in 1882 under the ownership of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. In 1896, the Raton Coal and Coke Company took over the mine’s operation. During the next few years, the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific Railroad accompanied the Raton Coal and Coke Company in building a battery of coke ovens, and the town of Gardiner started to grow.

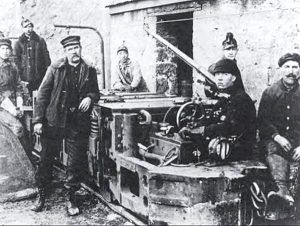

The first mine was originally part of the Blossburg operations, but as Gardiner developed, it became known as the Old Gardiner Mine. The mine was located west of the town, up Gardiner Canyon, with coal seams 6 -7 feet thick and its own tipple. Gardiner tracks of the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific Railway ran south to connect with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway for distribution to buyers.

In 1896, the Raton Coal and Coke Company took over the mine operations. The same year, a battery of 300 coke ovens was built. Coke is a by-product of processing coal and was used for smelting copper ore. All of the coal camps in Dillon Canyon sent their coal to Gardiner for coking and processing. The coke ovens often ran day and night, creating almost a permanent haze around the area.

In 1897, Gardiner gained its post office. By 1898, Gardiner had a washing plant with two Robinson-Wiggs coal washers, cleaning 800 tons of coal daily. The Blossburg Mercantile Company had a large brick building in the town, and part of the structure was used as a dance hall and movie theater. Behind the store were tennis courts. There was a dinky barn for the small locomotives that ran in the mines and to the coke ovens, a machine shop, a mule barn, an assay office, and a bathhouse for the miners.

In July 1899, several African-American families were brought into Gardiner from Alabama to break a strike at the mines. They were put to work at the coke ovens, which was often considered the hardest job in the mining communities and the mines. The 1900 Census lists 300 Blacks at Gardiner. They lived at the south end of town, across the creek, in their own community at the base of a low hill. When someone died in the black community, they were buried in unmarked graves on the hill’s flat top, while other residents of Gardiner were buried in Raton.

The population of Gardiner in 1900 was 985. The company had plans for big expansions by 1901, which came to fruition with the closing of the Blossburg mines and the shifting of operations to Gardiner, which employed 267 men. Cushmer’s Saloon and Barbershop was built in 1902. The saloon had a partition down the middle to separate the Black men from the rest of the population. However, fights often broke out, and the partition was demolished.

In 1905, the Raton Coal & Coke Company was sold to the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain & Pacific Company, who took over the operations. The community had a Catholic and a Methodist Episcopal church, a Ladies Club, a Reading Circle, a band, basketball and baseball teams, and a Sportsmen’s Club. The town also boasted a hotel and an amusement hall.

Gardiner was distinguished from the other camps by having a hospital in a simple wood structure for all miners in the area, including those as far away as Koehler. The hospital was built in 1905 and staffed with two resident doctors and five nurses. It was greatly enlarged in 1916 and eventually had room for 40 patients, an operating room, and a laboratory.

The St. Louis, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific Company opened the New Gardiner Mine in 1910–11 on the east side of Dillon Canyon and spent $50,000 equipping it. A tram line was installed to haul coal to the screening plant across the valley. In 1915, Gardiner produced 172,634 tons of coal.

There were two schoolhouses in Gardiner. The first one, with two rooms, was on the west side of the community. Sunday school was held in this schoolhouse. After 1918, the school was moved to the north end of town, against the hill.

All of the Gardiner houses were built by 1915, and most had four rooms. Most were made of coke cinder blocks, but a few were made of adobe. There was a water pump between every two houses, and there was no refrigeration other than 50-pound blocks of ice.

By 1917, new railroad tracks, an improved washer, a coke-breeze recovery plant, and a large warehouse had been added.

During the early 1920s, Gardiner was at its peak with 1,000 residents. But in 1929, the Great Depression started a downhill slide from which the town would never recover.

In June 1939, the mines’ available coal ran out, and most production was shut down. However, some coke processing continued during World War II to support zinc smelters in the war effort. Once the mines closed, most people moved away, and the post office closed in 1940. The hospital closed the same year, and the front part was sold and moved to Raton to be used as a motel office.

The machine shop operated until 1954 to service the equipment still in operation at some other mines. Afterward, all activity ceased, and Gardiner became a ghost town.

Today, very little remains of the old mining camp except for sidewalks, foundations, and low walls. However, the doctor’s house’s ruins, the lamphouse, and the dinky barn remained in 2010. One of the banks of ruined Coke ovens is the most obvious remnant.

Today, the property is owned by the Vermejo Park Ranch. All access to the town is blocked off except for ranch guests, who pay a hefty price for a night’s lodging.

Gardiner is the only ghost town in Dillon Canyon that visitors can see from public property. Take South Fifth Street out of Raton around the golf course to the locked gate, where the old coke ovens can be viewed.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2025.

Also See:

Coal Mining Towns of the Vermejo Park Ranch

St. Louis, Rocky Mountain & Pacific Company

Sources:

New Mexico Archaeology

New Mexico Geological Society

Sherman, James & Barbara; Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico, University of Oklahoma Press, 1975

Varney, Philip; New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns: A Practical Guide; University of New Mexico Press, 1987