Battles:

Before the Civil War, residents in the southern part of the New Mexico Territory had long complained that the territorial government in Santa Fe was too far away to address their concerns adequately. Their sense of abandonment was further confirmed at the beginning of the Civil War when regular troops were withdrawn from the area. As a result, a secession convention was held at Mesilla, New Mexico, in March 1861, where citizens voted to join the Confederacy and formed militia companies to defend themselves.

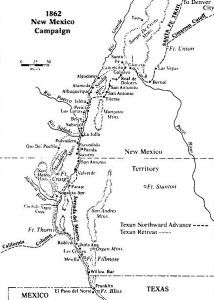

With Union troops gone from the southern part of the New Mexico Territory and Texas, the 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles under Lieutenant Colonel John R. Baylor were sent to occupy the series of forts along the western Texas frontier and advance into New Mexico to attack the Union forts along the Rio Grande.

About six miles southeast of Mesilla sat the tiny post of Fort Fillmore. Established initially to control the local Apache, the post had declined over the years, fallen into serious disrepair, and its troops removed. However, they reinforced the fort when the Union learned that the Texans were entering the territory.

First Battle of Mesilla

On July 24, 1861, 250 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles troops crossed the Rio Grande into Mesilla, arriving to the cheers of the population. A company of Arizona Confederates quickly joined Baylor there. Planning to attack the Union forces at Fort Fillmore the next day, they were thwarted by a Confederate deserter who informed Fort Fillmore’s commander, Major Isaac Lynde.

Taking offense, Lynde left a small force behind to guard the fort and marched on Mesilla on July 25, leading about 380 Union troops; he approached the town and demanded Baylor’s surrender. When the Confederates refused, the Union opened fire with its mountain howitzers, and the infantry was ordered to advance. However, heavy sand and cornfields interfered with this attack. Lynde then ordered his cavalry and three Regiment of Mounted Rifles companies to charge the Confederate forces.

Able to repulse the oncoming Union troops, both sides began skirmishing at long range. After three Union enlisted men died and two officers and four other men were wounded, Lynde ordered a return to the fort. The Battle of Mesilla resulted in a Confederate victory.

At sunset on July 26, Baylor ordered his artillery and more cavalry to reinforce him while the rest of his command moved to attack the fort the next day. That same night, Baylor’s men managed to capture 85 of the fort’s horses, which formed most of the fort’s transportation. Foreseeing the oncoming attack, Lynde destroyed the ammunition and supplies and the fort and retreated northeast towards Fort Stanton, some 150 miles to the northeast.

In pursuit on July 27, the Confederates captured several straggling Union troops and soon overtook Lynde’s command, who had been reduced to only about 100 men as they crossed the dry Organ Mountains. The prisoners were paroled, and Baylor returned to Fort Fillmore.

The Battle of Mesilla officially established a Confederate Arizona Territory, consisting of the southern portion of the New Mexico Territory and Arizona. It paved the way for the Confederate New Mexico Campaign the following year.

In August 1861, Baylor established the Confederate Arizona Territory, installed himself as its military governor, made Mesilla the capitol, and declared martial law.

Second Battle of Mesilla

Less than a year later, in June 1862, Arizona rebels and the New Mexican Militia fought another battle near Mesilla. Known as the Second Battle of Mesilla, the engagement ended with a Union victory, though neither side had any casualties. However, the Confederate forces lost precious supplies and several horses, forcing them to retreat. The rebels officially withdrew from Mesilla a few days later, on JunJune 7t was the last engagement between Union and Confederate forces in the Confederate Arizona Territory.

Sibley’s New Mexico Campaign (February-March 1862)

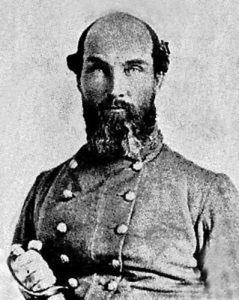

Led by Confederate Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley, southern troops invaded northern New Mexico Territory beginning in February 1862 to gain control of the American Southwest, the goldfields of Colorado, and the ports of California. In one of the most ambitious Confederate campaigns of the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the rebels hoped to establish control of the American West and open an additional theater in the war.

In the Spring of 1861, Sibley, a Louisianan who had just resigned from the U.S. Army, met with Confederate President Jefferson Davis and outlined a strategy to take over the American West. The plan called for an invasion along the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains, seizing Colorado Territory at the height of a gold rush and Fort Laramie, Wyoming, the most important garrison along the Oregon Trail.

Sibley then focused on areas farther west to attack mineral-rich Nevada and California. His strategy also included purchasing or invading the northern Mexican states of Chihuahua, Sonora, and Lower California.

The highly ambitious plan was made more manageable by carrying minimal supplies, capturing supplies at Union forts and depots along the Santa Fe Trail, and living off the land. He also planned to recruit new soldiers along the way, confident that there was much Confederate sentiment and cooperation in the sparsely defended deserts.

President Davis agreed to the plan and gave Sibley a brigadier general’s commission.

Leading more than 2,000 troops, Sibley left San Antonio, Texas, in November 1861, stopping in El Paso to recruit more soldiers. They then marched onward to Mesilla, the Confederate Capitol of Arizona Territory. On December 20, 1861, now in command of the Army of New Mexico, issued a proclamation taking possession of New Mexico in the name of the Confederate States. He called on the citizens to abandon their allegiance to the Union and to join the Confederacy, warning that those “who co-operate with the enemy will be treated accordingly, and must be prepared to share their fate.”

In February 1862, Sibley led his men northward up the Rio Grande Valley toward the territorial capital of Santa Fe and the storehouses at Fort Union. Along the way, Sibley’s first objective was to capture Fort Craig, New Mexico.

Battle of Valverde

Making their way across and up the east side of the Rio Grande to the ford at Valverde, north of Fort Craig, the Confederates hoped to cut Federal communications between the fort and military headquarters in Santa Fe. However, on February 20, 1862, some 3,000 men led by Union Colonel Edward Richard Sprigg Canby left Fort Craig to prevent some 2,500 Confederates from crossing the river. When he was opposite them, across the river, Canby opened fire and sent the Union Cavalry over, forcing the Rebels back. The Confederates halted their retirement at the Old Rio Grande riverbed, which was an excellent position. After crossing all his men, Canby decided that a frontal assault would fail and deployed his force to assault and turn the Confederate left flank. Before he could do so, though, the Rebels attacked. The Union forces were able to rebuff a cavalry charge. Still, the main Confederate force made a frontal attack, capturing six artillery pieces, forcing the Union battle line to break, and causing many Federal troops to flee. Canby then ordered a retreat.

In the meantime, more Confederate reinforcements arrived, and Sibley was about to order another attack. After battling for two days, Canby asked for a truce, by a white flag, to remove the bodies of the dead and wounded. Left in possession of the battlefield, the Confederates claimed victory, but they had suffered heavy casualties, an estimated 187. The Union also suffered an estimated 202 casualties.

Although a Confederate victory, Sibley determined he had lost too many men and supplies to take Fort Craig. He headed north around the post to Albuquerque, where the Federals had stored $250,000 worth of goods. Starting from Valverde on February 23, they reached Albuquerque on March 2. However, no battle ensued, as the defenders and supplies were gone.

The Confederate troops advanced slowly through the imposing peaks and buttes of the Jemez and Sangre de Cristo mountains toward Santa Fe. However, their progress was very slow due to the loss of many horses at Valverde, requiring many soldiers to march. They also had lost much of their transportation in the Battle of Valverde, causing them to carry the wounded. Though slow, they continued northwestward, reaching Santa Fe on March 13. Sibley detached 600 men to plunder the city, but once again, they found no federal ammunition or supplies. Sibley’s men then headed to Fort Union, some 90 miles northeast of Santa Fe.

In the meantime, the Confederates’ slow advancement allowed reinforcements from Colorado, under Colonel John Slough’s command, to reach Fort Union. Slough, the senior officer at the fort, took command, reporting to Colonel Edward Canby at Fort Craig. Canby instructed Slough to “harass the enemy by partisan operations, obstruct his movements, and cut off his supplies.” Slough interpreted this as authorization to advance. He soon gathered 1,342 men from Fort Union and began the trek to Santa Fe.

Battle of Glorieta Pass – Led by Confederate Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley, southern troops invaded northern New Mexico Territory beginning in February 1862 to gain control of the Southwest, the gold fields of Colorado, and California’s ports. In one of the most ambitious Confederate campaigns of the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the rebels hoped to establish control of the American West and open an additional theater in the war. See Full Article HERE!

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

Also See:

See Sources.