Traveling from Del Rio to Sanderson, Texas, along the Pecos Trail, one encounters a ghost town and ghost ranch experience rich in history. The 120-mile drive is situated in the Chihuahuan Desert, which is broken by numerous small mountain ranges and low-level river valleys formed by the Rio Grande and the Pecos Rivers.

Langtry – The Only Law West of the Pecos

Pumpville – Railroad Ghost Town

From the county seat of Val Verde County—Del Rio to the county seat of Terrell County—Sanderson, the long stretch across an arid terrain provides numerous peeks at lifestyles long past, from 4,000-year-old Native American art sites at Seminole Canyon to the Wild West days of Judge Roy Bean at Langtry, railroad history, and numerous old ghost towns that are crumbling in the desert heat.

When the Galveston, Harrisburg, and San Antonio Railroad made its way through the area, several townsites and stations developed to fuel the steam engines. Soon afterward, numerous large ranches developed in the area, shipping their cattle along the railheads. Later, when a highway was paved through the region, several small areas along the road were designated as rest and service stops.

An oasis in the desert, Amistad National Recreation Area is located on the U.S. side of the International Amistad Reservoir.

Lake Amistad

Just about ten miles northwest of Del Rio, the visitor crosses Lake Amistad. Straddling the United States and Mexico, the lake is renowned for its excellent water-based recreation and camping opportunities. It is surrounded by a landscape rich in prehistoric rock art and a wide variety of plant and animal life. The National Park Service administers the Amistad National Recreation Area.

Though the Comstock, Texas area is still called home to several hundred people,

it looks pretty “ghost towny.” Kathy Alexander.

Just about 29 miles northwest of Del Rio, Comstock, Texas, like many other small towns in the area, got its start when the Galveston, Harrisburg, & San Antonio Railroad came through the area in 1882. When the town was first platted, it was called Sotol (or Soto) City, but was soon renamed Comstock, after a railroad dispatcher named John B. Comstock.

The town was granted a post office in 1888, but its remote location and limited resources kept it from growing quickly. Comstock was at the height of its activity between 1888 and 1910 when the Deaton Stage Line operated between the town’s railroad depot and the city of Ozona, some 60 miles north.

Although it is home to several hundred people today, it is also filled with abandoned buildings. See Full Article HERE.

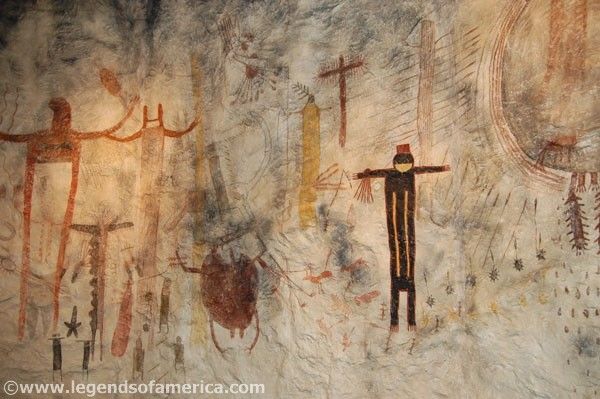

About ten miles northwest of Comstock is Seminole Canyon State Park. The historic site, spanning more than 2,000 acres, features jagged canyons carved through the Chihuahuan Desert, where the Pecos River meets the Rio Grande. The area has been inhabited by humans for approximately 12,000 years, during which time they lived in natural rock shelters carved into the canyon walls. Thousands of years later, another culture, known as the “Archaic people,” inhabited the dry rock shelters, leaving their mark on the environment through approximately 200 rock paintings throughout the area. The park contains some of the most outstanding examples not only in Texas but in the world. Extensive pictographs of the Lower Pecos River Style, attributed to the Middle Archaic period approximately 4,000 years ago, adorn rock shelters throughout the canyons of the Lower Pecos River. See more HERE!

The Pecos River & Frontier Folklore

The Pecos River, one of the major tributaries of the Rio Grande, flows through New Mexico and Texas before emptying into the Rio Grande near Del Rio, Texas. Famous for its frontier folklore, the river flows out of the Pecos Wilderness, through rugged granite canyons and waterfalls, and passes small, high-mountain meadows along its 926-mile journey.

Correctly pronounced “pay-cuss,” the headwaters of the Pecos River are located north of Pecos, New Mexico, at an elevation of over 12,000 feet on the western slope of the Sangre de Cristo mountain range in Mora County. The river then flows for 926 miles through the eastern portion of New Mexico and neighboring Texas before it empties into the Rio Grande near Del Rio. The river was named “Pecos” by the Spanish from the Keresan name of the Pecos Pueblo.

The river played a significant role in the Spanish exploration of Texas. In the latter half of the 19th century, “West of the Pecos” referred to the rugged frontiers of the Wild West. See the Full Article HERE.

Vinegarroon & the Pecos River Railroad Bridge

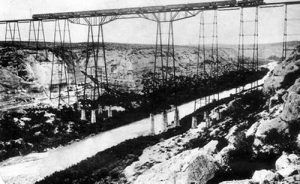

A few miles beyond the Pecos River Highway Bridge is a lookout that designates the old townsite of Vinegarroon. The Pecos River Railroad bridge is visible in the distance.

The Pecos River was once a significant barrier to transportation, particularly across the deep gorge that marked its confluence with the Rio Grande. The Galveston, Harrisburg, and San Antonio Railroad built its tracks through the area in 1882, constructing the first railroad bridge over the Pecos River.

Work began in late 1891 and was completed within three months at a cost exceeding $250,000. An engineering marvel, the bridge, known at the time as the Pecos River Viaduct, spanned 2,180 feet and towered 321 feet above the river.

Later, Vinegarroon was abandoned, and most of its residents moved to nearby Langtry. Today, nothing remains of old Vinegarroon.

There is no access to the bridge or the old town site of Vinegarroon, as the site is on private property. Continue the journey just a few more miles to the northwest, where the old townsite of Shumla once stood. See the Full Article HERE.

Shumla- Another Railroad Casualty

All that’s left of Shumla is an old combination motel, gas station, and store that closed in the 1970s. By Kathy Alexander.

About eight miles northwest of Seminole Canyon State Park is the old townsite of Shumla. Yet another stop along the Galveston, Harrisburg, & San Antonio Railroad, this station, situated on the north side of the tracks, was established at the same time as the other railroad towns of the area – 1882. The year before, hundreds of Chinese and European immigrants worked to connect the eastern and western halves of America’s second and southernmost transcontinental rail line.

When we visited, only a scattering of buildings remained, and a reader had advised us that they were slated for demolition. See the Full Article HERE.

This large rock shelter was the scene of several prehistoric buffalo jumps. More than 11,000 years ago, during the early Paleoindian era at the end of the last Ice Age, the people of the time began stampeding herds of buffalo over the edge of a cliff overlooking the shelter in a narrow box canyon that empties into the Rio Grande. This technique of stampeding buffalo off a cliff is usually associated with the Plains Indians, hundreds of miles to the north. Bonfire Shelter is the southernmost buffalo kill site in North America and is also the oldest known site.

Stone tools, including Paleo-Indian arrowheads and radiocarbon dating of charcoal from small hearths, date to 10,000 years ago, when herds of the giant bison were driven over the cliff above. The most recent evidence shows that about 800 B.C., Late Archaic hunters succeeded, on at least one occasion, in driving as many as 800 buffalo off the same cliff. Killing far more than they could make use of, they left behind a rotting heap of partially butchered carcasses that spontaneously combusted in an intense blaze that reduced most of the bones to ash. This event is where the shelter takes its name. See Full Article HERE.

Langtry – Home of the Only Law West of the Pecos

Along with several other old towns in the region, Langtry got its start when the Galveston, Harrisburg, & San Antonio Railroad was built through the area in 1881. Beginning as a grading camp for the railroad workers, it was first called Eagle Nest for the nearby creek. When it became known that a Justice of the Peace was wanted for the area, Roy Bean was quick to volunteer, and on August 2, 1882, he became the “legal authority” in the area. He first operated his “justice” out of his tent saloon in Vinegarroon, another railroad camp to the south.

As the vast majority of railroad workers moved to Langtry, so did Judge Roy Bean. There, he quickly set up another tent saloon on railroad land, to the chagrin of Cezario Torres, who owned most of the land beside the railroad right-of-way. See full article HERE!

From Langtry, the Pecos Trail continues through the Chihuahuan Desert on U.S. Highway 90 before coming to a Texas Historic Marker commemorating the town of Pumpville.

Located about 2.5 miles north of the historic marker on FM Road 1865, Pumpville got its start as a water station for the Galveston, Harrisburg, & San Antonio Railroad in 1882. It soon gained a telegraph office and a small crew for the station. It was first called Samuels, but five years later, when the railroad drilled wells at the town to supply water for the trains, the town was renamed Pumpville. The railroad also built a large storage tank and housing for the railroad crews.

Today, it is an entire ghost town, but amazingly, its Baptist Church continues to draw a small congregation from miles around.

Cedar Station

The Pecos Trail continues to snake its way through the arid terrain onwards to Dryden and Sanderson. Along the way, there are several glimpses of old ranches, homes, and one “almost town” that was called Cedar Station. Though it sounds as if it might have been another of the many stops along the railroad, this little place came later to serve the travelers along the highway. Today, nothing more than a few decaying buildings remain, but it once boasted a service station that also sold food and drinks, a small motel, and a home for the Smith family, who once operated the stop.

Another few more miles down the highway brings the traveler to the tiny town of Dryden, once the site of one of the last Texas train robberies.

Dryden – Dying Along the Railroad

Tiny Dryden, Texas, with a population of about 13, is one of just two communities in Terrell County, which spans 2,358 square miles in the Chihuahuan Desert of southwest Texas. Like Dryden, the county, comprised chiefly of large sheep and cattle ranches, is sparsely populated, with only about 1,100 people calling it home.

Once the headquarters for numerous large ranches and several businesses, today, all that remains is about a dozen people and a general store that is as sparsely stocked as the county’s population. However, the area has a rich history, including the last major train robbery in Texas, ancient Native American pictographs, Black Seminole Scouts, and more. See the full article HERE!

Sanderson – The Town Too Mean For Bean

The last stop on this picturesque portion of the Pecos Trail is Sanderson, Texas, the county seat of Terrell County. Known as the Cactus Capital of Texas and the gateway to the Big Bend Wilderness Area, Sanderson is home to most Terrell County residents. Situated on U.S. Highway 90, about midway between San Antonio and El Paso, it has a rich and colorful past that is evident in many of its historic buildings.

One of the first to settle in the area was a man named Charlie Wilson, who established a saloon near the site of the proposed railroad terminal. Calling it the Cottage Bar Saloon, Wilson also bought all of the lands that would later become the Sanderson townsite. In these earliest days, he also had a competitor – none other than Roy Bean, who also hoped to capitalize on the incoming railroad crews. However, when Bean opened another saloon, Wilson spiked his whiskey with “coal oil,” and Bean soon moved eastward to Vinegarroon and Langtry. Wilson’s riddance of his competitor would later earn the name “Town Too Mean for Bean.” See full article HERE!

The Texas Pecos Trail traverses a diverse landscape, featuring sand dunes, underground caverns, spring-fed pools, numerous rivers and creeks, lakes, and more. See much more HERE!

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2025.

Also See:

Texas Ghost Town Photo Gallery

See Sources.