“Mobeetie was patronized by outlaws, thieves, cut-throats, and buffalo hunters, with a large percentage of prostitutes. Taking it all, I think it was the hardest place I ever saw on the frontier except Cheyenne, Wyoming.”

— Charles Goodnight of the Goodnight/Loving Trail

Long before Mobeetie, Texas, became an “almost ghost town,” the vast plains were home to the Apache Indians. In the 1700s, the Kiowa and Comanche took over the area, running the Apache out. However, the Kiowa and Comanche were defeated in the Red River War of 1874, and the white settlers quickly began to settle the area.

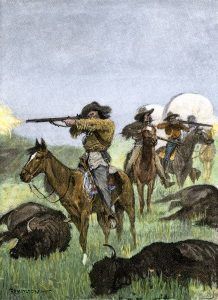

In the spring of 1874, buffalo hunters moved down from Kansas, and a camp was formed near Sweetwater Creek called Hidetown, about two miles southeast of the site where Old Mobeetie stands today.

In 1875, the United States government established Fort Cantonment about 2 miles northeast of Hidetown to keep the Indians on reservations in Indian Territory and establish law and order in the region. On June 5, 1875, Major H.C. Bankhead and the 4th Cavalry arrived with several infantry companies to establish the new fort. The first buildings at the fort were made of sharpened cottonwood posts placed into the ground at close intervals, joined by poles fastened across the top. Larger logs were used as ceiling beams stacked with layers of brush and weeds above the beams. The structure was then covered with adobe and packed into the spaces between the posts. Board buildings would quickly replace most picket buildings, but some were still used until 1890.

Nearby, Hidetown quickly began to develop with the settlement of the Fort and gained the name Sweetwater City. Dominated by three Dodge City, Kansas men by the names of Charles Rath, Bob Wright, and Lee Reynolds, the settlers supplied buffalo hides to the three men, who made provisions available to the settlement. With the fort established, the Dodge City men built a trading post, and Sweetwater quickly grew to a population of about 150 people. The three Dodge City men claimed to have bought over 150,000 buffalo hides while they were in Sweetwater.

William (Billy) L. R. Dixon, the hero of the Second Battle of Adobe Walls in 1874, was wagon master of a bull train in Sweetwater for a time. Running the train for Lee Reynolds of Dodge City, Kansas, Dixon mastered ten 7-oxen teams of three wagons to a team bringing provisions into Sweetwater and taking loads of buffalo hides back to Dodge City.

By the summer of 1875, Sweetwater, catering primarily to the soldiers at the fort, had a Chinese laundry, a restaurant, a dance hall, and several saloons. Like many Old West settlements, the town was primarily home to bullwhackers, outlaws, buffalo hunters, and gamblers.

The restaurant was run by Tom O’Loughlin and his wife, Ellen, who was said to have been the only virtuous woman in the settlement. The other women in the small town were the dance hall and saloon girls. Numbering about 15, the girls worked the many Sweetwater Saloons, which held such names as the Pink Pussy Cat Paradise, the Buffalo Chip Mint, and the White Elephant. One saloon called the Ring Town Saloon, located about 2 ½ miles northwest of Sweetwater, was designated for black men only – primarily those Buffalo Soldiers employed at the fort.

The owner of the main dance hall was Bill Thompson, brother of the noted Ben Thompson, gunman of Austin, Texas, who was killed in San Antonio.

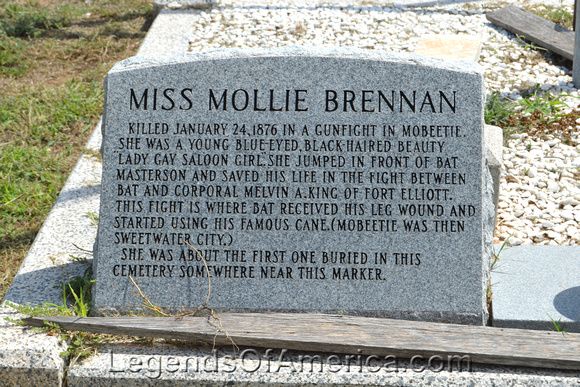

Sometime in 1875, Bat Masterson, who had scouted for Colonel Nelson A. Miles during the Red River War, landed in Sweetwater. Working as a faro dealer in Henry Fleming’s Saloon, Masterson became embroiled in an argument with Sergeant Melvin A. King over a card game and a dance hall beauty named Mollie Brennan. The argument quickly led to gunplay, and King was left dead.

However, in the melee, King’s shot passed through Mollie Brennan’s body, killing her, and then hit Masterson in the pelvis. The injury caused Bat to walk with a limp for the rest of his life. In 1876, Masterson returned to Dodge City, Kansas, where he became a lawman for many years. Other visitors to Sweetwater during this lawless time included Patrick F. Garrett and Poker Alice.

By February 21, 1876, the fort was renamed Fort Elliott by General Order No. 3 of the Division of Missouri. By that time, Fort Elliott had officer’s quarters, sufficient barracks for six companies of enlisted men, a headquarters building, a hospital, laundress’ quarters, storehouses, and cavalry stables, all built of lumber.

Most of the supplies needed for the Fort were brought in from Dodge City, Kansas. Civilians who settled near the post produced food, which they found a ready market for at the post.

On April 12, 1876, Wheeler County was one of 26 counties created out of Clay County Territory and was named for Supreme Court Justice Royal T. Wheeler.

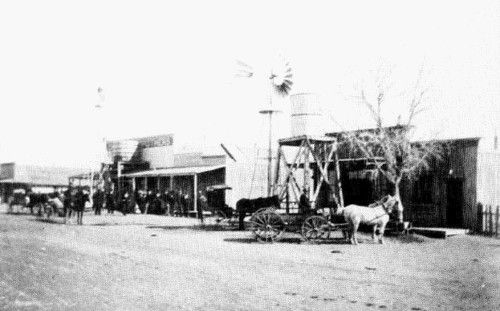

Mobeetie, Texas, in the early 1900s.

In 1878, it was discovered that Sweetwater was located on the Military Reserve, and the town had to relocate. Moving two miles northwest to section 45 proved to be a boost for the settlement, with its location nearer to the fort.

Wheeler County was officially organized in 1879 by a petition signed by 150 qualified voters, and Sweetwater was elected as the county seat. The settlement then applied for its own post office in the town of Sweetwater. However, the name was rejected because Texas already had a town by that name. It occurred to some to ask the local Indians the name of Sweetwater as spoken in their language.

The word was Mobeetie, and it became the name of the town. It wasn’t until many years later that a Comanche related that Mobeetie didn’t actually mean “sweet water” but instead meant “buffalo dung.”

By 1880, Fort Elliott was able to procure hay, some lumber, shoes, saddles, wagon wheels, clothing, and many staple foods from the locals. These early entrepreneurs constituted the first manufacturers in the Texas Panhandle.

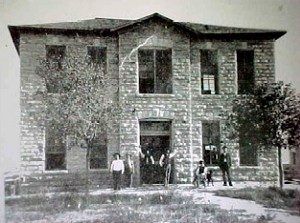

Old Mobeetie Stone Courthouse.

Throughout the 1880s, Mobeetie was the commercial center of much of the Panhandle, connected by a mail route with Tascosa to the west. Rath’s mercantile store catered to area ranches, and Fort Elliott dominated the economy. Mobeetie’s main street expanded to include livery stables, wagon yards, a barbershop, a drugstore, a blacksmith shop, two hotels, numerous boarding houses, and an increased number of the ever-present saloons.

The first courthouse in the Texas Panhandle was built in Mobeetie in 1880 by Irish stonemasons who quarried the stone from the Emanuel Dubbs homestead nine miles east of Mobeetie. Just one year later, Mobeetie became the judicial center of the 35th District, which comprised 15 counties. Several lawyers set up shop, including Temple Houston, son of Sam Houston, who served a term in Mobeetie as district attorney before his election to the state Senate.

Mobeetie continued to have its share of gamblers, rustlers, and prostitutes. However, Captain George W. Arrington and his Texas Ranger Company effectively deter the lawless element. Arrington was elected county sheriff in 1882 and, throughout his term, made his home in the two-story stone jail, which still stands today. The Texas Panhandle, the region’s first newspaper, began operation in the same year. By 1886, Mobeetie had a population of about 300.

In 1888, just eight years after its construction, the stone courthouse was condemned because of structural flaws. The Irish stonemasons were unaware that metal pins were required to hold the stone together. A wooden structure across the square from the county jail replaced the courthouse.

In 1889, the Texas Panhandle newspaper became the Wheeler County Texan. In the same year, a rock schoolhouse, which also served as a union church and community center, was built, replacing an earlier wooden structure. On holidays, the community center held dances and horse races in the small town.

By 1890, Fort Elliott was no longer needed to defend the settlers from the Indians, so they abandoned the post. At an inventory taken in August of 1890, the Fort had 13 sets of officers’ quarters, four barracks, two offices, a hospital, chapel, library, guardhouse, seven storehouses, and several other outbuildings.

The army moved out permanently in October 1890. Before the Fort closed down, Mobeetie had a population of 400.

An immediate decline in population occurred when Fort Elliott was abandoned, and the town made several attempts to secure a railroad through the area. However, all attempts failed. In the early 1890s, the area saw a religious revival, and in 1893, a revival meeting resulted in 300 conversions to the faith. Baptist and Methodist churches were constructed soon afterward, and all of the town saloons were closed.

The town’s troubles increased on May 1, 1898, when a tornado took seven lives and destroyed many of the buildings that were never rebuilt. People began to move away.

By 1900, the ranching industry began to give way to farming, resulting in a substantial increase in cultivation. Still, Mobeetie had dwindled to only about 128 people, and the Wheeler County Texan newspaper was discontinued.

In 1902, the Rock Island Railroad was built westward across the Panhandle from Oklahoma to Amarillo, and the towns of Crossroads, Lela, Shamrock, Norrick, and Benonine grew while small Mobeetie struggled.

Another blow occurred in 1907 when a controversial election made the town of Wheeler, 12 miles southeast of Mobeetie, the county seat. In 1908, the wooden courthouse was moved to Wheeler. But Mobeetie hung on with a school, a bank, a lumberyard, and various other businesses. In 1910, Mobeetie’s population had risen a little from the prior decade, having a population of 250.

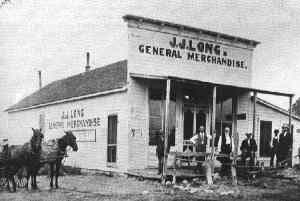

Historical Photograph of Mobeetie General Store.

In 1916, the county initiated the construction of a highway across the southern part of Wheeler County, which would later become US Highway 66. A road also started from Shamrock to Wheeler to Mobeetie.

In 1923, the first gas well was drilled near Shamrock, and just one year later, the first producing oil well was drilled in the county. By the end of the 1920s, the entire southwestern part of the county was dotted with oil and gas wells, tank batteries, and pipelines.

In 1929, the area finally got its long-awaited railroad, but the Panhandle and Santa Fe Railway built its line from Pampa, Texas, to Clinton, Oklahoma, just north of Mobeetie, missing the town by two miles. The post office and most of the businesses moved closer to the railroad, and soon, “New Mobeetie” was born, incorporating “Old Mobeetie” as part of the new city. Most of the remaining residents moved closer to the railroad, but the stone jail and a few other abandoned homes remained in Old Mobeetie.

The railroad and the area’s increased agriculture increased the population to 500 by 1940. However, forty years later, in 1980, the numbers had fallen again to less than 300 due to the improved highways and the proximity to Pampa and other Panhandle towns.

In 1984, Mobeetie had nine businesses, a bank, a post office, three churches, and modern school facilities for 12 grades. Although a few people still reside at the old townsite, most houses are abandoned and falling.

Today, only one bank, the post office, the elementary school—which was formed from three other small towns close to Mobeetie—and a diner along Texas Highway 152 exist in this almost forgotten town. “New Mobeetie is also a near ghost town with only about 100 residents.

The old county jail in “Old Mobeetie” has since become a museum after serving as a private residence for several years and the local VFW Hall. The museum features artifacts from both Mobeetie and Fort Elliott. On the site is also a crude flagpole and an outdoor jail cell, which is all that remains from Fort Elliott. The museum and several outbuildings are open year-round from 1:00-5:00 p.m. daily except Wednesdays. Manned by volunteers, donations are graciously accepted.

Considered the “Mother City” of the Panhandle, Mobeetie is located 20 miles east of Pampa, Texas, on State Highway 152 in northwest Wheeler County.

©Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

Also See:

Billy Dixon – Texas Plains Pioneer

See Sources.