The Platte County area was originally part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. When Lewis and Clark were sent to explore the new territory, they passed through the area in 1804. They described it as beautiful, with fertile soil and diverse plant and animal life. Their report encouraged traders and trappers to come to the area.

1853 Weston Engraving by Hermann Meyer.

In 1836, the Platte Purchase was made, in which the Federal Government “officially” bought two million acres of land from the Iowa, Sac, Fox, Sioux, and Algonquin Indians for $7,400. After the Platte Purchase, the Indians were moved to a reservation in Northeast Kansas.

The first people to settle in what would soon become Weston were two young soldiers from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1837. Rowing up the Missouri River in a canoe, they discovered that the river made a natural bay at the foot of what would later become Weston’s Main Street. The bay, prime for a steamboat landing or ferry, prompted the young men to purchase the property. Selling off a few of their lots, Weston officially began. Joseph Moore, one of the two soldiers, built the first cabin at the corner of what is now Market and Main Streets.

Early settlers arrived from many southern states, including Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Virginia, bringing with them the important crops of tobacco and hemp, as well as their southern customs, including slavery. Soon, emigrants from Austria, Germany, Scotland, Ireland, and Switzerland discovered the area, attracted by the rolling hills that reminded them of their homelands. The Platte Purchase allowed these new settlers to homestead their property if they cultivated at least ½ acre and built a dwelling.

In 1838, Ben Holladay, one of Weston’s first entrepreneurs, arrived. At first, he established a small tavern. Later, he became involved in several local businesses.

By 1839, Weston had grown to a population of 300. Initially, the primary source of income for the settlers was tobacco farming. As early as 1840, tobacco was floated on rafts to Glasgow, where it was packed into hogsheads and shipped on steamboats to St. Louis and Cincinnati.

Tobacco is still cultivated in the Weston area to this day.

Later, the farmers discovered that hemp, a product used to make rope, provided an even higher profit, and it became the main cash crop of the time. However, hemp cultivation is challenging work, requiring the stalks to be combed into fibers. Here, these first southern settlers actively depended upon their southern custom of utilizing slave labor for the work.

In 1841, Ben Holladay became the first postmaster of the community. He also bought out a stage line and opened Holladay’s Overland and Express Company, capturing seven mail routes serving the Nebraska and Wyoming territories. Holladay would eventually become known as the “Stagecoach King” when, in later years, he acquired almost a monopoly on the stage, mail, and freight business between the Missouri River and Salt Lake City.

Stagecoach.

However, his primary source of business in Weston in 1841 was outfitting the Mormon wagon trains headed to Salt Lake City. Holladay would also later build the International Hotel, one of the best places to stay in Weston, before moving west. Unfortunately, the hotel later burned down and no longer stands today.

The town continued to grow as area businesses actively traded with Fort Leavenworth and the local Native Americans. Large warehouses were established along Market Street, close to the wharf, to serve the burgeoning river trade.

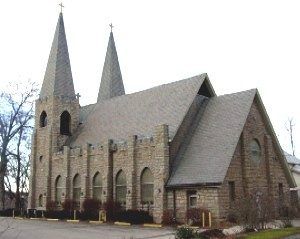

In 1844, the Holy Trinity Church was built, situated high on a hill on Cherry Street. The Presbyterian Church, also built in the 1840s, would ring its bell to alert dockworkers that a steamboat was coming. The Presbyterian Church is now the Christian Assembly, located at the corner of Washington and Thomas. Both historical churches are still active today.

With the coming affluence, early settlers began to build stately, columned Federal-style two-story houses, much like those they had left behind in the South. The town residents also built several commercial buildings that reflected the influence of French traders from New Orleans and Canada, as well as a German influence from the emigrants who arrived in the area.

In 1846, the St. George Hotel (now the Hotel Weston) was built. It was one of the three in Weston during its heyday but the only historic hotel remaining. In the 1800s, the hotel catered to the working man, providing 47 rooms on the top two floors. On the first floor, there was a saloon, sample rooms where traveling salesmen could exhibit their wares, a tobacco shop, a restaurant, and two retail spaces.

Between 1846 and 1848, Ben Holladay furnished supplies to General Stephen Kearny’s Army during the Mexican War. Continuing to expand his empire, Holladay moved to California in 1852.

By the early 1850s, Weston’s population had grown to 5,000, making it the second-largest port in Missouri, behind only St. Louis. At this time, as many as 300 steamboats would dock in Weston from April through November, unloading supplies for Fort Leavenworth and shipments west on the Oregon Trail. On their return trip, the steamboats would be loaded with tobacco, hemp, lumber, animal hides, and fruit.

Buffalo Bill Cody resided in Weston for a time. After Cody’s father, Isaac, was attacked and stabbed while giving an antislavery speech in Kansas, Bill came to live with his uncle, Elijah Cody, in his home at 600 Main Street.

Missouri Steamboat.

In 1855, the first in a chain of disasters began a decline from which Weston would never recover. The first was a major fire in the city’s downtown district, which destroyed most of the businesses. However, Weston persevered and rebuilt its business district. Most of the buildings today were built between 1855 and 1860.

Though Ben Holladay had already moved west by 1856, his business ventures were far-flung. Recognizing the potential profit of the natural limestone springs of the Weston area, he built the McCormick Distilling Company in 1856. The distillery, still in existence today, is the oldest continuously operating distillery in the United States.

During this time, Platte County and the Weston area were quickly becoming embroiled in the Kansas-Missouri border wars, which preceded the Civil War.

Given the proximity to “Bleeding-Kansas,” the town had sympathizers on both sides of the conflict. Still, given their dependency upon slave labor, most of the population was pro-slavery, along with the rest of Missouri.

The “genteel” community formed a secret society. It drew up a resolution, which provided for the “scrutinizing and reporting” of any “suspicious looking persons” who might be taking arms to Kansas or inciting abolition. There were about 500 members of the secret society who publicly announced their opposition to any pro-abolition members of the community, any businesses who profited from trading with those “Bleeding-Kansans,” and any who objected to the “regrettable excesses” of the vigilantes.

Missouri Border Ruffians, also called Bushwhackers.

Backing this secret society were the so-called Border Ruffians, who were notorious pro-slavery thugs. In 1857, the Chicago Tribune reported these ruffians as “a queer-looking set, slightly resembling human beings, but more closely allied… to wild beasts… They never shave or comb their hair, and their chief occupation is loafing around whiskey shops, squirting tobacco juice, and whittling with a dull jack-knife.”

Fervent abolitionists lived side by side with those whose way of life was built upon the institution of slavery. Bands of armed men ranged on both sides of the border, making ordinary life impossible. The value of slaves and land dropped by half, and long before the war was officially declared in 1861, Weston experienced hand-to-hand fighting in the streets.

By 1858, Weston’s population was second only to St. Louis, Missouri. Then, in the midst of the pre-Civil War chaos, another disaster occurred when a significant flood filled the Muddy Missouri and destroyed the port of Weston.

When the floodwaters receded, the river’s channel moved several hundred yards to the west (to the other side of the railroad tracks today). Though this did not deter river traffic, it was a blow to the community. However, in 1859, the railroad was built, extending north from Weston, which gave the community new hope.

Though Missouri was filled with pro-slavery sympathizers, the state joined the Union in 1861, and many of Weston’s young men went to war. In November 1861, the Weston area saw its first and only organized battle at Bee Creek when the Union Army Major left St. Joseph for Platte City to capture Silas Gordon, a noted Southern partisan. Despite the 500-man Union force and two pieces of artillery, Gordon slipped away and began gathering his friends to attack the Union force. The major let it be known he intended to stay in Platte City, but instead marched out and made for Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, on the Weston turnpike. The Southern sympathizers gathered about 50 men and made a hasty stand at the Bee Creek Bridge to stop the federal force.

The small group of southerners was able to stave off the federal advance guard, but when the U.S. troops opened fire with their artillery, almost half of the Confederates fled. The fight lasted for about an hour and only ended when the Southerners ran out of ammunition. The entire battle was visible from the land of Red Barn Farm. Three of the Confederates were captured, and two of them were later executed because two Unionists were killed at the Bee Creek skirmish. The third man, named William Kuykendall, was spared. He survived the war and moved west, and interestingly, served as a judge at the first “trial” of Jack McCall, who had murdered Wild Bill Hickok.

The following month, the U.S. Army sent another force that captured two more suspected partisans and executed them at the bridge. One of the soldiers marked the letters “U.S.” on the bridge railing in the blood of the executed men.

The town was torn apart by the devastation of the Civil War, never to recover its prior heyday status. After the war ended in 1865, all Hemp production stopped, it being too labor-intensive to make profitable without slavery. In 1869, the railroad was extended south to Kansas City, but it was too late for Weston’s recovery. By 1870, the town’s population had fallen to just 900 people.

If all that Weston had been through wasn’t enough, the city was yet to experience two more disasters. The first event that changed Weston’s life forever was the devastating flood of 1881. This time, when the waters receded, the river slipped into an old channel almost two miles away, permanently ending any riverboat traffic.

Then, in December of 1890, Weston experienced another devastating fire in its downtown district. Weston was on its way to becoming a ghost town.

Weston, MO, 1890.

However, the people of Weston persevered. Tobacco was still a strong agricultural product, and many of its area residents stayed, though it would be more than sixty years before the city saw a renaissance.

In the late 1950s, Weston’s rich heritage resurfaced, and the Weston Historical Museum was founded in 1960. The community began to look at its historic buildings, and more than 100 antebellum homes started to be restored. Many people in Weston now believe that the flood of 1881 was the “disaster” that “saved” the town for today. Unlike Kansas City and St. Joseph, which are no longer on a growth path, Weston’s original buildings remained intact.

In 1972, twenty-two blocks of Weston were designated as a Historic District and placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The 1980s witnessed a revitalization of the downtown business district as empty storefronts were purchased or leased, showcasing antiques, collectibles, specialty items, and other novelties.

Today, Weston’s businesses, organizations, and individuals have joined together to restore Weston to a place of pride, billing itself as the “Town that Time Forgot.” The area is lined with antique shops and restaurants, allowing visitors to step back into the past easily.

Other Weston attractions include a 1,055-acre state park on the Missouri River, the McCormick Distilling Company, established in 1856, the former German Lutheran Evangelical Church, built in 1867, which houses the cellars of the Pirtle Winery, and O’Malley’s 1842 Irish Pub, where visitors can sample Irish beer in the cellar of the oldest brewery west of the Hudson River.

Just a short trip from Kansas City, Weston is tucked away in the Missouri River Bluffs, 25 miles north of Kansas City. Weston has a little to offer everyone, including history, romance, shopping, casual and fine dining, wineries, and museums.

Hotel Weston, by Kathy Alexander.

The Hotel Weston, formerly the St. George Hotel, built in 1846, has now been fully restored and is again open for business. The fire in December 1890 left the building in ruins, but two street-side brick walls were left standing. With an added brick facade, those two walls are part of the current building, which dates to 1891. The building is now ten feet shorter than it originally was. Except for the period between the fire and the reconstruction, the hotel was continuously operated until 1984, when a small fire occurred in one of the three apartments on the first floor. Today, the hotel features a bakery, wine bank, and spa in its historic surroundings.

Nearby Weston Bend State Park, administered by the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, offers scenic overlooks, camping facilities, and hiking and biking trails. Four tobacco barns are located within the park’s boundaries, and one is used to tell the story of tobacco production.

The Snow Creek Ski Area offers a variety of outdoor adventures. Its snowmaking capabilities keep the slopes open from mid-December through mid-March.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2025.

Also See:

See Sources.