After the Mexican-American War in 1848, few Americans realized or even dreamed of the vast mineral potential of the territories they had so recently wrested from their Mexican neighbors. Fewer still would have thought that southwestern Colorado, an area disregarded because of its rugged terrain, severe winter climate, and hostile Ute Indians, would be crisscrossed by miners and prospectors and that permanent settlement would be so rapid. From the beginning of the Territorial Period in 1861, southwestern Colorado was a mineral resource frontier that invited exploitation.

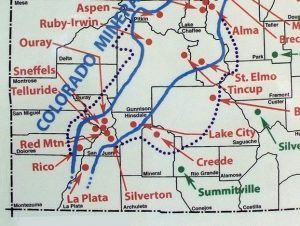

The history of early southwestern Colorado mining, up to the Ute removal in 1881, can be summarized by three primary stages: early gold placer mining near Baker’s Park and in the Tin Cup mining district during the early 1860s; the era of silver mining along the Animas River around Silverton and in the Elk Mountain region of modern Gunnison County during the early 1870s; and the development of hard-rock mining throughout the San Juan country, along with the growth of the Gold Brick mining district on Quartz Creek, near present-day Pitkin in Gunnison County, in the late 1870s and early 1880s.

In 1858 and 1859, the first Colorado Gold Rush occurred when the William Green Russell party found “colors” while prospecting along Cherry Creek, Ralston Creek, and Newlin Gulch near present-day Denver. In July 1859, the first “arrastra,” a Spanish ore-crushing device, was built at the Gregory Diggings near Blackhawk. At the same time, placer gold was found and worked at Buckskin, Mosquito, Hamilton, Tarryall, Montgomery, and Fairplay on branches of the South Fork of the South Platte River. In 1860, a second and more considerable rush into the central Rockies occurred. Most prospectors headed to the Gregory diggings near Central City, which, being overcrowded, caused the diffusion of miners in all directions.

Outfitted in California, Gulch, a prospecting party led by Charles Baker, acting on persistent rumors of mineral wealth in the San Juan Mountains, moved into that rugged region during the spring of 1860. Reports of rich finds made their way back to the more established camps, and several hundred eager treasure seekers followed Baker to the San Juan country in the upper Animas River Valley. In April 1861, prospectors spread out from “Baker’s Park” and began digging nine miles north in Eureka Gulch. By this time, Baker’s earlier reports had proved misleading, for placer operations were ineffective in bringing satisfactory returns. In May of 1861, the camp at Baker’s Park broke up, and many prospectors moved south to the fertile Animas River Valley. Animas City was laid out, and several buildings were constructed. Most of the prospectors gave up, however, and with the outbreak of the Civil War, many of these early miners, Baker included, were drawn into service for the Confederacy. Despite the lack of substantial discoveries on the first major prospecting expedition into the San Juan mining district, it was apparent that southwestern Colorado’s mineral resources were located in a broad belt that stretched diagonally across the territory from the San Juan country in the southwest to the Elk Mountains along the Continental Divide, in the northeast.

Gold was first discovered in the Tin Cup District of Gunnison County in 1860 by Jim Taylor. Then, in 1861, Fred Lottis led parties across the Continental Divide from Granite, Colorado, and worked placer gold fields in the region. Evidence of early mining activity was apparent near present Waunita Hot Springs, approximately 25 miles east of Gunnison, where rotted flumes used in earlier placer mining were discovered in the 1870s. The first actual mining camp in the Gunnison country, Minersville, in Washington Gulch just north of the present-day town of Crested Butte, had a population of about 200 in 1861. In 1862, nearly 1,000 prospectors swarmed into the area and took out nearly a million dollars in gold by placer mining. By 1863, with the placers played out, and due to the increasing hostility of the Ute Indians, most camps were deserted. Not until 1872, when discoveries of silver-bearing rock were made in the Elk Mountains, would large-scale mining operations resume.

Little in the way of mineral exploration occurred in southwestern Colorado during the mid-1860s because of diminished placer gold deposits and the absence of permanent settlement in the region. Yet the fact that mining had been undertaken on the western slope served as a constant reminder of potential mineral wealth. Although Baker’s Park and the San Juans were well within the boundaries of the Ute Reservation (established in 1868), efforts to prospect the region resumed in 1869. This time, prospectors came from the west, when Adnah French and Dempsey Reese, coming from Arizona, prospected along the Dolores River. By 1870, they reached the Animas River, moved into Baker’s Park, and began digging near Silverton. At the same time, a party composed of Sheldon Shafer and Joe Flarhieler, traveling along the Dolores River on their way to Montana from Santa Fe, located what is now part of the Shamrock, Smuggler, and Riverside lodes of the Atlantic Cable Group, which they named The Pioneer.

In 1870 and 1871, two significant discoveries in the San Juan region caused further mining excitement. The location of the Little Giant Mine in 1870, on the north side of Arrastra Gulch about four miles northeast of modern-day Silverton, and the discovery of rich silver veins along Henson Creek that were to comprise the Ute and Ulay lodes just west of present-day Lake City brought prospecting parties into the area.

Maroon Bells, Elk Mountains, Colorado, by Pedro Lastra, Flickr

During the early 1870s, numerous mining expeditions searched the Elk Mountains between present-day Crested Butte and the mouth of Rock Creek. The Benjamin Graham and the George and Lewis Waite parties prospected in and around the Schofield Pass and Crested Butte areas, where silver deposits were located. Jim Brennan, a miner from Denver, became intrigued by the tales of mineral wealth in the Elk Mountains. In 1872, he led a small group of treasure seekers into the rugged Elk range and found fissure veins, which were reportedly enormous. The rumors of large ore bodies that followed such prospecting expeditions as Waite’s, Graham’s, and Brennan’s led to the first scientific mineral exploration of the Gunnison country. Doctor John Parsons, in 1873, explored the mineral and agricultural resources of the area to erect an ore reduction plant on Rock Creek. Accompanying Parsons was a geologist, Sylvester Richardson, who discovered silver along Spring Creek, east of modern Crested Butte, and large coal deposits west of that future town, along Ohio Creek. Based on the quality and extent of the minerals he located, Richardson intended to establish a settlement with easy access to those discoveries. This early plan climaxed in the building of Gunnison City some years later.

Mining in southwestern Colorado during the early 1870s was exploratory, as had been the case in the 1860s. The one difference was the realization that the location of the region’s mineral resources, rather than in gold placer deposits along the streams and rivers, lay in veins deep within the mountainous terrain. Despite the richness of the discoveries and the establishment of numerous mining camps in southwestern Colorado during the early 1870s, several years passed before the prospecting pioneers were bold enough to winter or face the ever-present threat of Indian attack within the region. Through the early 1870s, miners, each fall, retreated east across the Continental Divide from the San Juans, wintered in Del Norte or Saguache, Colorado, and then returned in the spring to resume work on their claims. To most miners, however, limited and seasonal operations were unacceptable. Transportation routes, advanced mining equipment, and permanent settlements were needed.

The potential mineral resources of the San Juan region received widespread attention across the Colorado Territory after initial gold and silver veins were located from 1869 to 1871. However, the beckoning mineral wealth knew no boundaries, and the Ute Reservation on the western slope was the scene of continual trespass during this period. Holding back the ever-increasing tide of prospectors who flooded the area was impossible. By 1873, Coloradans pressed for revising the 1868 Ute Indian Treaty, which legally barred entrance to the southwestern Colorado mining frontier. The Brunot Treaty, enacted in 1873, opened four million acres in the heart of the San Juans to impatient treasure seekers and settlers. During the next two decades, prospectors made the ceded lands the scene of one mining rush after another. Ironically, immediately following the opening of the San Juans, the Indian Agency at Los Pinos Creek in Cochetopa Park became a way station for many of the migrating prospectors. From the agency came a story of one such prospecting party, which continues to be a source of interest and amazement.

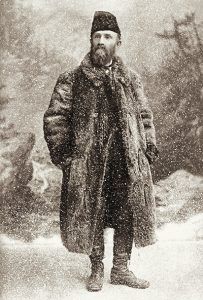

In January of 1874, a party of 21 men, on their way to the central Rocky Mountain gold fields from Utah, stopped near present-day Montrose at the encampment of Chief Ouray. Despite Ouray’s warnings of severe winter weather ahead, six men, Israel Swan, Frank Miller, George Noon, James Humphrey, and guide Alfred Packer, left the camp and continued eastward. On April 16, 1874, Packer arrived at the Los Pinos Agency alone, claiming to have been abandoned by the others. Packer related his tale of hardship, suffering, and near starvation, yet he looked healthy and well-fed for a man who had endured such a harrowing ordeal. Packer requested liquor for his first meal, shunning offers of food, which was a suspicious action to the agency dwellers. The guide’s conduct while at the agency continually invited suspicion to the point where Agent Charles Adams accused Packer of killing and robbing the five prospectors. Under pressure, Packer confessed to the killings. In June of 1874, while passing near present-day Lake City, Harper’s Weekly photographer J. A. Randolph stumbled onto the bodies of the five slain men. A shanty was found near the spot, and leading from it to the bodies was Packer’s well-worn trail, showing that he had made frequent visits to his victims and had subsisted on their flesh. Today, a monument and plaque commemorate the five “who were murdered early in the year 1874 while pioneering the mineral resources of the San Juan country”. Packer never paid in kind for his gruesome deeds. After having his death sentence reversed and another forty-year sentence commuted, Packer died in Littleton, Colorado, on April 23, 1907, allegedly a confirmed vegetarian.

During the mid-1870s, many Coloradans, concerned over the falling population of the central Rockies and along the Front Range, began advertising the Territory. In a climate of “boosterism”, people such as Ovando Hollister, in his Mines of Colorado, publicly stated beliefs that a new era was soon to dawn on Colorado, and that to exaggerate on the subject of mineral resources, especially in the southwestern portion of the territory, was almost impossible. The many accounts of rich soil and mineral wealth in the Rocky Mountains brought about a public clamor for scientific surveys to examine these rumors of riches. Unlike the earlier Gunnison and Fremont expeditions, exploration parties were directed to inspect the virtues of the Rockies rather than report on their particular evils as barriers to progress.

In response to public demand, Congress sent out a new group of experts between 1867 and 1878 under the direction of the Army and the Department of the Interior. To make the continuing search of Colorado’s mountains more productive, there was a need for additional topographic knowledge. To fulfill this need, Ferdinand V. Hayden and William H. Jackson, under the direction of the Department of the Interior, examined geologic formations, flora and fauna, the topography, and the scenery of much of southwestern Colorado in the years from 1874 to 1875. Railroad builders, mining investors, and land developers instantly seized upon the information published in the Geological and Geographical Atlas of Colorado and Portions of Adjacent Territory.

By 1875, the effects of the Brunot Treaty, government surveys, and booster-style advertising of southwestern Colorado were seen in numerous intensified mining rushes to the San Juan area.

Much of the San Juan mining excitement in the mid-1870s was attributable to rich finds made outside Lake City when Enos Hotchkiss, a partner with Otto Mears in the construction of the Saguache and San Juan Toll Road, located the Hotchkiss mine in 1874, three miles south of Lake City, which later became the well-known Golden Fleece. With the opening of that mine, a significant rush occurred locally, and Hotchkiss, with others, incorporated the town of Lake City in 1875. Wanting the outside world to know of the silver and lead deposits near Lake City, Hotchkiss published a newspaper, The Silver World, to advertise the area. The widespread distribution of the paper helped to quickly transform struggling Lake City from a cluster of cabins into a roaring mining town of 2,000 inhabitants. The continued production of the Hotchkiss Mine (later the Golden Fleece) and the nearby Ute and Ulay Mines and the erection of the Crooke and Company smelter made 1876 a promising year for the Lake City mining district.

As was typical of a boom period, a large influx of people into a popular mining area meant overcrowding and the subsequent diffusion of miners and prospectors to neighboring regions. By 1876, mineral discoveries were made on the upper Lake Fork of the Gunnison River at the confluence of Cottonwood Creek, and here the Sherman townsite was laid out. Other towns created around this rich area included Whitecross, Burrows Park, and Tellurium. South on Lost Trail Creek, the town of Carson developed, and for several years, it was the largest town in the southern part of Hinsdale County. At the same time, along Henson Creek, west of Lake City, the Henson townsite, Capitol City, and Rose’s Cabin developed due to mineral exploration in the area.

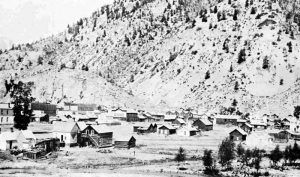

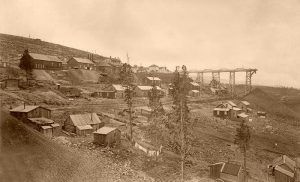

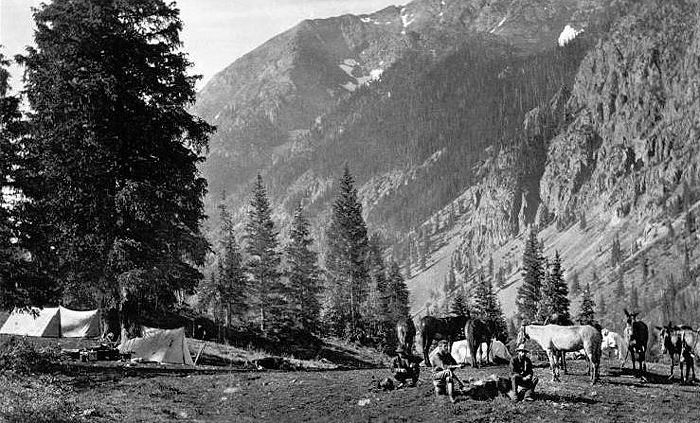

Camp in Baker’s Park, Colorado, courtesy of Denver Public Library

The San Juan mining rush of 1874 was mainly centered in those areas that had been sites of placer prospecting in the 1860s and early 1870s. Consequently, the Baker’s Park region in the Animas River Valley received some 2,000 prospectors in 1874, and it was estimated that one thousand lode mining claims were staked during that single year alone. Mining activity occurred on Hazelton Mountain, north of Silverton in Arrastra Gulch. Ore taken from mines like the Aspen and the Prospector were treated in Green and Company’s newly erected smelter, just north of Silverton.

Baker’s Park had been continuously prospected by one particular group of miners from 1871 to 1874. This party, composed of Francis Snowden, Dempsey Reese, and N. E. Slaymaker, filed a claim on land in Baker’s Park in September 1874. The townsite of Silverton was established, later to be incorporated in November 1876. Silverton became the hub of the mining boom in the mid-1870s and, as a result, gave new life to the mining camps in the Animas River Valley. Howardsville and Eureka were both platted in 1874. Animas Forks, slower to develop due to temporary inaccessibility, was laid out in 1877.

In the year following the Silverton boom, Augustus “Gus” Begole and John Eckles headed northwest from Green Mountain above Howardsville to prospect along the Uncompahgre River. Locating gold and silver deposits in the Uncompahgre Valley, the two men returned to Silverton to stake their claims and replenish their supplies. In early fall, Begole’s and Eckles’ success was matched when A. J. Staley and Logan Whitlock discovered the “Trout and Fisherman” lode near where Canyon Creek joins the Uncompahgre River. Returning from Silverton to the place of their previous finds, Begole and Eckles again found rich veins, which they named “Mineral Farm.” The location of these mineral deposits in the summer and fall of 1875 created a rush to the area from the nearby mining towns of Silverton, Howardsville, and Mineral Point. Judge R. F. Long and Captain M. W. Cline were among those early prospectors. Realizing the area’s vast potential, the two men laid out a townsite at the juncture of Canyon Creek and the Uncompahgre River, which they named Ouray. In August 1876, Ouray was incorporated and had, by that November, a population of 400 inhabitants.

In the three years between 1877 and 1879, lode prospecting was rapidly extended in the entire San Juan region. The Silverton, Lake City, and Ouray mining districts, during this time, produced large quantities of valuable ores, and further mineral locations prompted intensive mining activity along Henson Creek, the Lake Fork of the Gunnison River, the Animas River, and the Uncompahgre River Valley. In 1878, the town of Ophir was laid out when rich discoveries were made near Mount Sneffels, on the upper waters of Canyon Creek in Poughkeepsie Gulch, and in Imogene Basin on Bear Creek, southwest of Ouray. Roads and trails were built from the town of Ouray to all these points to compete with the roads built from Lake City and Silverton to tap these ore districts. In 1878, Charles Sharman established San Miguel City on the San Miguel River to service the influx of prospectors coming to the valley. The mining towns of Placerville and Columbia in the San Miguel River Valley were laid out at this time due to mineral rushes to the region. Otto Mears, one of the principal stockholders in the Columbia Town Company, helped reincorporate the town as Telluride in September 1879. In 1878, John Glasgow and Sandy Campbell came northwest from La Plata City, on the La Plata River, and began successfully developing the Grand View Mine and the Atlantic Cable Group in the Dolores River Valley, southwest of Ophir. In the spring of 1879, Colonel J. G. Haggerty, on a visit to Ouray, reported that ore from “N****r Baby Hill” proved very rich in silver. The towns of Ouray. Silverton, Ophir, and San Miguel City emptied their hundreds into the Rico region. Rico was incorporated on February 25, 1880, and the Grand View smelter began operations shortly after.

In seven years from the enactment of the Brunot Treaty, the San Juan region of southwestern Colorado had been the scene of remarkable growth and development. Evidence of this growth, a consequence of the expanding Colorado mining frontier, was seen in establishing permanent communities. Miners and prospectors, no longer the only Anglo-Coloradans inhabiting the region, were joined by town promoters, merchants, lawyers, doctors, clergymen, and road builders. On May 1, 1881, telephone service was extended to Lake City, and in the following summer, lines reached Silverton and Ouray. The original Territorial Counties of southwestern Colorado, Lake and Conejos, were dissected in 1874 into the new counties of Rio Grande, Hinsdale, and La Plata. San Juan County was made from the northern part of La Plata County in 1876. Following Colorado Statehood in 1876, Ouray County was created from the western portion of San Juan County, and Gunnison County was formed from the western part of Lake County. In 1881, Ouray County was divided to establish Dolores County.

At the same time, the San Juan country witnessed tremendous growth of towns and mining operations, similar occurrences took place in the central Rockies, near Leadville, Colorado. Massive migrations to that mining district, as with all such boom periods on the Colorado mining frontier, prompted success for a few and dashed hopes for many. Lack of opportunity in Leadville after 1879 motivated a small army of argonauts west to look at the increasingly acclaimed mining regions across the Continental Divide.

The miners who came to the Gunnison country in 1879 and 1880 were not unaware that the region was located on a direct line between Leadville and the San Juan mining region, nor had they forgotten the strikes made there in the early 1870s. The initial rush to the Gunnison area in the spring of 1879 was concentrated in a few well-known regions within the Colorado Mineral Belt. Prospectors descended into the Taylor Park region near Willow Creek through Cottonwood Pass. They established the towns of Hillerton and Virginia City when rich discoveries were made nearby at the Gold Cup Mine. Virginia City, founded initially as Tin Cup, had a camp population of nearly 2,000 by the summer of 1879. Virginia City was incorporated in August 1880 but reincorporated as Tin Cup on July 24, 1882.

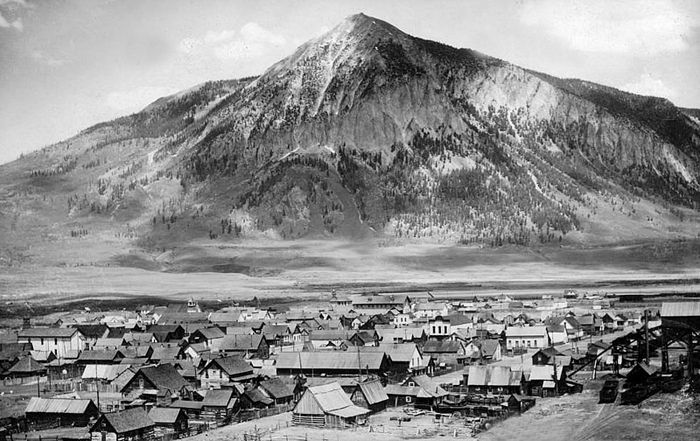

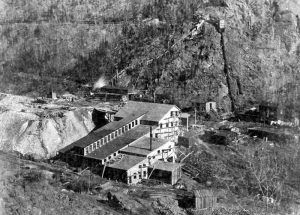

South of Tin Cup, on Quartz Creek, a mining party led by Frank Curtis established the Quartzville camp in the Gold Brick Mining District in early 1879. A major rush to the district occurred when assays on ore samples from the area’s mines ran as high as $2,000 per ton. A townsite was laid out in April 1879 and named Pitkin. By mid-May, close to one thousand people had lived in the town, and many had mined the surrounding area. North of the Taylor Park and Gold Brick districts, west of the Coal Creek camp of Crested Butte, rich silver discoveries led to the organization of the Ruby Mining District in May 1879. The towns of Ruby and Irwin, merged by 1880, were focal points for thousands of prospectors and miners through 1884. At the juncture of East River and Copper Creek, north and west of Ruby, the town of Gothic was incorporated on July 17, 1879, when large silver-producing mines, such as the Sylvanite, attracted nearly 5,000 miners and settlers. Near the headwaters of Tomichi Creek, along the Continental Divide, the towns of White Pine, Tomichi, and North Star, the last to be opened by the 1879 rush, sprang up within four miles of each other. The town’s short-lived heyday resulted from many prospectors interested in the area’s rich lead and silver deposits. Amid all the excitement during 1879, Crested Butte and Gunnison City were destined to become the two most important towns in the Gunnison country, even though they were not directly dependent upon gold and silver themselves.

Although not incorporated until 1880, the town of Gunnison owed its inception to the silver mining expeditions conducted in the early 1870s. Sylvester Richardson, a geologist in one such mining party, became interested in the country’s potential and resolved to begin a colony there. Richardson organized a stock company, and 20 cabins were erected on the present site of Gunnison by the summer of 1874. As a result of the mining excitement in the San Juans and the central Rockies and due to a lack of mineral exploration in the Gunnison country during the mid-1870s, the settlement was, for all purposes, abandoned. Persistent in his resolution, Richardson formed another town company in June 1879 after the region received much acclaim for its numerous silver deposits. The company, composed of Richardson, John Evans, Henry Olney, London Mullin, and Alonzo Hartman, plotted the townsite of Gunnison City in April 1880. Gunnison was transformed almost overnight from a sparsely settled camp into a roaring boom town. By its incorporation, an estimated 25,000 people crowded into the Gunnison country, and the town’s population reached nearly 2,000. Richardson’s foresight was quickly rewarded as Gunnison grew to be the hub and supply point of the surrounding mining region, with trails and roads leading in all directions. In little more than a year after its incorporation, Gunnison would experience yet another boom with the addition of rail transportation.

The camp of Crested Butte came into existence when, in 1877, coal was discovered at Mount Crested Butte by the Jennings brothers. The following year, Howard F. Smith began the town of Crested Butte after purchasing an interest in the Jennings’ coal operations. By 1879, the town served as a way-station for the hordes of prospectors en route to the surrounding gold and silver mining country. Growth resulting from Crested Butte’s reputation as a supply town led to its incorporation in 1880. The town’s accessibility to Gunnison through the Slate, East, and Gunnison River valleys and its nearby coal deposits would make it a strategic railroad station by 1881.

Much of the early mining development took place well above the timberline, with the attendant high cost of living and transportation causing delays in the opening of southwestern Colorado. The consolidation of claims and the permanent occupation and development of the region was accomplished under almost incredible hardships and by a mere handful of committed people. The failure of small smelting operations at places such as Ophir and Rico in the 1870s led to a gradual recognition that such enterprises were futile in this remote corner of the State, where supplies of suitable ores and fluxes were unobtainable, fuel was expensive, and business conditions were unfavorable. The early mining camps of southwestern Colorado were isolated, a condition based not solely on distance but on terrain and climate. Isolation did not produce the self-sufficiency often described as a typical characteristic of the American frontier. Since the early mining towns did not attract agricultural settlement, foodstuffs, and more durable commodities had to be imported from outside the immediate vicinity, often as far away as Canon City or Alamosa, the nearest railheads at the time. This also meant that the ore to be shipped out had to be valuable to meet the high transportation and refining costs.

In the development of the mining frontier in southwestern Colorado, during the early period, the presence of Ute Indians was troublesome and often dangerous. Still, roads were an even more immediate concern. The need for better transportation was not new to the Colorado mining district. The miner had to open and then develop vital transportation arteries before he could hope to make his ventures profitable. The history of early transportation in southwestern Colorado is in the development of the toll road. Rugged mountains, steep gorges, and river valleys could be breached only by roads built by private enterprise.

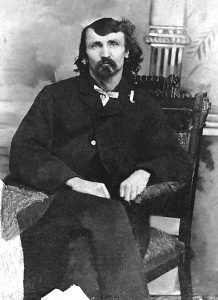

Isolated as they were, the mining camps and districts offered a bountiful opportunity for anyone adventurous enough to tie them together with a good road system. Such a man was Otto Mears. Often called the “Pathfinder of the San Juans,” he led pack trains, built toll roads, maintained freighting outfits, and finally became a railroad builder. He was also heavily involved in politics and Indian affairs. The chronicle of his toll road building began in 1870 when he incorporated the Poncha Pass Wagon Road Company, which constructed the first well-designed road between the San Luis and Arkansas River Valleys. Realizing the San Juans were undergoing a mining rush in the mid-1870s, Mears and associates incorporated 1874 their second road, the Saguache and San Juan Toll Road. The returns from this road proved so great that another road was built to Lake City, this time from the supply town of Del Norte. The Antelope Park and Lake City Toll Road, completed in November 1875, cut, by one-half, the distance traveled from Lake City to Del Norte.

The Ouray and Lake Fork Wagon Road Company was incorporated in November 1876 by several Ouray merchants. The proposed road was to be built from Ouray to the Lake Fork of the Gunnison River and then to a point on the Saguache and San Juan Toll Road. By spring of the following year, with only a few miles of road built, Mears bought the company’s stock. Deciding that the former owners’ plan was too ambitious, he built a road from Ouray to the present town of Montrose. Wishing to connect this road with his Saguache and San Juan Toll Road, Mears incorporated, in September 1877, the Lake Fork and Uncompahgre Toll Road Company. By the following summer, the Lake Fork and Uncompahgre Toll Road ran west from the Barnum Post Office on the Lake Fork of the Gunnison River and crossed the Little Blue and Big Blue Creeks and the Cimarron River into what is now Montrose. With the completion of this road, Mears had built a continuous road with fine grades from Ouray to Barnum, a distance of over one hundred miles.

Otto Mears profited from toll road construction during the great mining rushes to the San Juan mountains in the mid to late 1870s. The mining boom in Gunnison country during 1879 and 1880 offered similar potential. Knowing that a route over Marshall Pass, from Poncha Pass to the new town of Gunnison, was feasible, Mears was quick to organize a company to build it. Work on the Poncha, Marshall, and Gunnison Toll Road was completed during the spring of 1880. By June 15, W. M. Outcalt, the superintendent of the Marshall Pass workforce, reported to the Gunnison News that the road was complete and that “all who travel it pronounce it the best road in the country.” Not everyone shared this optimistic view, however. One day, Otto Mears stopped to exchange the time of day with a couple of unlucky travelers stuck in a mud hole on Marshall Pass. Mears listened sympathetically and anonymously as the men spoke a profaned and passionate denunciation of any man who would dare charge a toll for a road in such a condition as the one on which they were presently stuck. After Mears listened quietly to their woes, he told them they would probably have the chance to meet Mears since he had seen the roadbuilder about ten miles back. With that, the “Pathfinder of the San Juans” rode on, apparently refusing to help the unfortunate gents out of their predicament. Whichever account was most accurate remains a point of speculation, yet Mears collected his toll for crossing Marshall Pass just the same. The Gunnison News reported that for a passage from Mears Junction on the Poncha Pass Toll Road to Gunnison, a wagon with a two-horse team was charged four dollars; a wagon with one horse was charged two dollars; a wagon with additional teams of horses cost two dollars per team; loose stock and pack animals cost 25¢ per head; and saddle animals cost 50¢ each.

In 1881 and 1882 alone, Mears and his associates completed the Dallas and San Miguel Toll Road, the San Miguel and Rico Toll Road, and the Durango, Parrott City, and Fort Lewis Toll Road. Much of the road building during this period was accomplished by upgrading existing but inferior roadbeds. In this fashion, between 1881 and 1883, he was responsible for reopening the Gunnison and Cebolla Toll Road and the Ouray and Canyon Creek Toll Road.

Between 1883 and 1884, Otto Mears began a task that would mark his finest achievement as a road builder. A road from Ouray to Silverton over Red Mountain (known as the “Million Dollar Highway”) was constructed in two stages. The first was a road from Ouray to Red Mountain, and the second was the completion of a road from Silverton to Red Mountain. With this construction, Mears economically linked the two important mining towns. Besides making travel to Ouray and Silverton easier, the new toll road also lessened freight rates on products hauled between the towns. It also was less expensive to haul ore down into the towns from the mines on Red Mountain. As a result, it became profitable to move lower-grade ore off dumps and send it to the smelters.

The completion of the Silverton-Animas Forks-Mineral Point Toll Road in 1886 marked a watershed in Otto Mears’ life, for, in the decade and one-half previous to this road’s completion, his principal achievements in transportation had been in the construction of numerous toll roads, in the future he would be primarily interested in the construction and operation of railroads. Since 1870, he had built a network of roads almost 450 miles long at a cost of nearly $400,000, the completion of which had an enormous impact on the development of southwestern Colorado. Freight could be moved into the area more cheaply, and lower-grade ore could be shipped profitably. It was no accident that southwestern Colorado experienced dramatic growth during the operation of Mears’ toll roads.

Otto Mears’ accomplishments were quickly copied by road construction in the Gunnison country. During the mining boom in 1879 and 1880, toll roads were completed in the Quartz Creek, Tomichi, and Taylor Park mining districts.

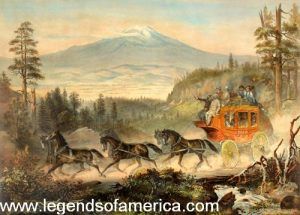

Access to mining camps and towns in southwestern Colorado was made more accessible by the construction of better road grades and stage lines, and freighting outfits quickly moved into the territory. With the completion of the Antelope Park and Lake City Road, the Barlow and Sanderson stage line began running from Del Norte to Lake City as early as 1876. Dave Woods, the dominant force of the freighting business in southwestern Colorado during the 1880s, constructed a wagon road over Cottonwood Pass into Taylor Park in 1877 to haul freight from Colorado Springs into that booming region. With the entrance of rail transportation to southwestern Colorado in the 1880s and 1890s, the stage and freighting businesses saw their most profitable times as “end-of-the-line” operations.

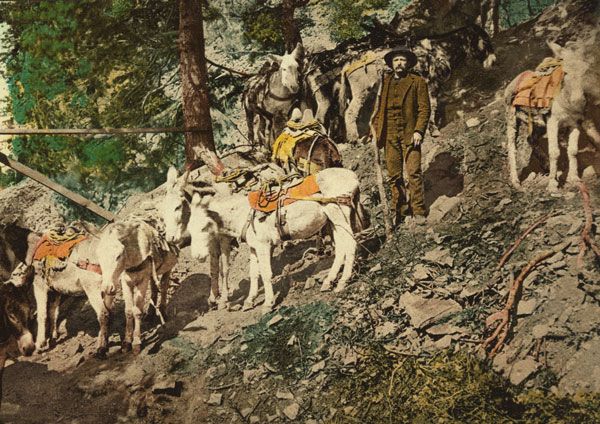

No history of early transportation in southwestern Colorado would be complete without mention of the homely and unromantic burro. This agile and sure-footed animal ensured the future for the struggling mining camps in the almost inaccessible Elk and San Juan Mountains. In 1874, the Greene and Company smelter machinery at Silverton was packed in on burros from Pueblo via Stony Pass, a distance of 250 miles. The pack trains in the early mining development of southwestern Colorado were the indispensable link that tied isolated camps to supplies and civilization.

While the mining camps in southwestern Colorado struggled to gain a permanent foothold from 1860 to 1881, the ill effects of rapid and extensive development became evident. With an undiscriminating enthusiasm so characteristic of mining, they rushed more into the business than was justifiable or desirable. Too many small claims were permitted on each section of the better-known lodes, resulting in shafts being sunk almost side-by-side. At the same time, the surface was cluttered with buildings, shaft houses, equipment, and waste dumps of neighboring companies. Stamp mills in great numbers were built before anyone attempted to determine how much ore would be brought to these plants. Many mining operations began without the precise technical knowledge of such projects. Finally, stripping the public domain of all trees near a camp gradually created a timber and fuel shortage, resulting in high prices for those once plentiful resources. A new era of consolidation based on efficient management loomed in the not-too-distant future.

The year 1881 marked the beginning of a new era as agriculture and rail transportation entered the southwestern Colorado frontier. That year alone, the Ute Indians were removed from the Western Slope, and the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad reached southwestern Colorado at Durango and Gunnison. Ten years earlier, agriculture, ranching, and permanent settlement throughout the entire region were premature speculations, but they became blossoming realities in the last two decades of the nineteenth century.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Also See:

Early Exploration and the Fur Trade in Colorado

Ghost Towns & Mining Camps of Colorado

Source: Bureau of Land Management