Pecos National Historical Park, situated on the historic Santa Fe Trail, encompasses thousands of acres of landscape that protect the Pecos Pueblo, its Spanish Mission, the Glorieta Pass Battlefield of the Civil War, Santa Fe Trail sites, and two 19th-century ranches.

Pecos Indians.

Historically known as the Pueblo of Cicuique, the Pecos Indians once controlled the trade route between Pueblo farmers of the Rio Grande and hunting tribes of the buffalo plains. The first Pecos Pueblo consisted of approximately two dozen rock-and-mud villages constructed in the Pecos River Valley around 1100 A.D. About 350 years later, the village had grown to house more than 2,000 people in a five-storied complex.

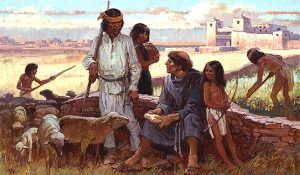

The Pecos Indians were an advanced tribe with a heritage deeply rooted in the Puebloan culture of the American Southwest. Like their Ancient Puebloan ancestors, the Pecos practiced ancient agriculture, religion, and architectural customs. Farming was essential to their livelihood. By applying an ancient agricultural technique that had originated in Mexico, the people of Pecos could supply most of their diet of corn, beans, and squash.

Farming influenced the architectural design of the Pecos village. The Indians built storerooms to set aside food for the winter and dams to regulate the water that flowed to their crops. Their impressive architecture included large multi-story houses built above the storerooms using adobe bricks. The Pecos erected a large wall to protect the village, which, according to one Spanish conquistador, was visible from a far distance.

Some of their most impressive structures were the kivas, subterranean pit houses used for religious and ceremonial purposes. Although they varied in shape and size, they were traditionally circular, with a hole in the center of the floor. The hole in the ground represented the connection to the underworld, which the Pecos and other Pueblo tribes believed was the place of origin for their people. The Pecos regularly prayed to the underworld through ceremonies and offered sacrifices to the spirits in the hope of receiving good fortune. They feared that failing to perform these rituals would upset the spirits, which in turn would cause their crops to die and their overall world to become unbalanced.

Though neighboring pueblos saw the Pecos as dominant, warfare between Pueblo groups was common. In addition, the frontier people of Pecos had to be vigilant with nomadic Plains Indians, who were often unpredictable. At trade fairs, Plains tribes, primarily nomadic Apache, brought slaves, buffalo hides, flint, and shells to trade for pottery, crops, textiles, and turquoise with the Pecos River Pueblos.

By the late Pueblo period, the last few centuries before the arrival of the Spaniards in the Southwest, this valley had developed into multi-storied towns overlooking the streams and fields that nourished their crops. In the 1400s, these groups gathered in Pecos Pueblo, which became a regional power. The Spaniards would soon learn that the Pecos could be powerful allies or determined enemies.

Coronado Expedition.

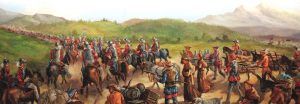

In 1540, the Pecos people first encountered Spanish strangers when Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, leading an army of more than 1,200 men, traveled to New Spain’s northern frontier in search of the legendary seven cities of gold, referred to as Cibola. Six months into the march, he rode into a cluster of Zuni pueblos near present-day Gallup, New Mexico. He attacked the Zuni at Hawikuh, taking over that principal town and its food stores for his famished soldiers.

When Coronado and his men reached the village of Cicuye, which would be called “Pecos” by the Spanish, 150 miles east, the reception was different. The Indians welcomed the Spaniards with music and gifts. There, a Plains Indian captive told of a rich land to the northeast called Quivira. In the spring of 1541, Coronado and his men searched for Quivira, wandering as far as Kansas. After finding only a few Indian villages, his Indian guide confessed that he had lured the army onto the plains to die, and Coronado had him strangled. Having failed to find Cibola, Coronado and his men turned back and returned to Mexico empty-handed, and the Pecos Indians settled back into their old ways.

Although Coronado’s expedition failed, the Spanish were still determined to colonize the Pueblo lands and convert the American Indians to Christianity. In 1598, Don Juan de Onate, accompanied by settlers, livestock, and ten Franciscans, crossed the Rio Grande and marched north to claim the land for Spain. He immediately assigned a friar to the Pecos Pueblo, the richest and most influential in New Mexico. However, these early Spanish missionaries failed, and after episodes of idol-smashing provoked Indian resentment, the Franciscans sent veteran missionary Fray Andrés Juárez to Pecos in 1621 as a healer and builder. Under his direction, the Pecos built an adobe church south of the pueblo. The most imposing of New Mexico’s mission churches featured towers, buttresses, and massive pine-log beams hauled from the surrounding mountains. The ministry of Fray Juárez from 1621 to 1634 coincided with the most energetic mission period in New Mexico, which had become a royal colony.

It was a Franciscan-led time of mission building and expansion. However, its success bred conflict, as the church and civil officials vied for the Pueblo Indians’ labor, tribute, and loyalty, which ultimately led to resentment among the Indians and the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. After decades of Spanish demands and Indian resentments, Indians in scattered pueblos united to drive the Spaniards back to Mexico in what became known as the Pueblo Revolt. At Pecos, loyal Indians warned the local priest, but most followed a tribal elder in revolt. They killed the priest and destroyed the church. The Spanish would not return to Pecos for another 12 years.

In 1692, Diego de Vargas was sent to visit Pecos. He and his men expected a fight but were awed by their warm welcome and the Indians’ willingness to assist the Spaniards in their quest to reclaim the American Southwest. The tribe accepted him and supplied 140 warriors to aid in the retaking of Santa Fe, New Mexico. A smaller church, built on the ruins of the old one, was the first mission reestablished after the Reconquest, and most Pecos sustained Spanish rule until it ended. In return, the Franciscans moderated their zeal, and the practice of encomiendas (paying tribute) was abolished. As allies and traders, the Pecos became partners in a relaxed Spanish-Pueblo community. The serene environment in the region lasted until the 1780s, when disease and Comanche raids devastated Pecos, reducing the population to less than 300. Long-standing internal divisions between those loyal to the Church and Spanish leaders versus those who clung to the old ways may have contributed to the decline of this once-powerful city. The function of Pecos as a trade center faded as Spanish colonists, now protected from the Comanche by treaties, established new towns to the east.

Pecos and the mission seemed almost ghostly when the Santa Fe Trail trade began flowing past in 1821. The old trail brought thousands of travelers heading west, including trappers, traders, Gold Rush seekers, adventurers, the U.S. military, and everyday Americans across this portion of New Mexico. Kozlowski’s stage station was an important stop along the trail. The Union Army would later use it in the Civil War Battle of Glorieta Pass and as the headquarters for the Forked Lightning Ranch. Santa Fe Trail ruts can still be seen in the park.

In 1838, the last survivors left the decaying pueblo and the empty mission church, joining their Towa-speaking relatives 80 miles west at Jémez Pueblo, where their descendants still reside.

During the Civil War, the Confederate plan for the West was to raise a force in Texas, march up the Rio Grande, take Santa Fe, turn northeast on the Santa Fe Trail, capture the stores at Fort Union, head up to Colorado to capture the goldfields, and then turn west to take California. It was intended as the killer blow by Confederate forces to break the Union possession of the West along the base of the Rocky Mountains.

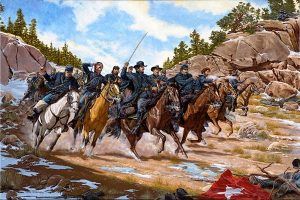

On March 26, 1862, Union and Confederate forces met at Glorieta Pass near the Pecos Pueblo. The battle raged for two days, and although the Confederates were able to push the Union force back through the pass, they had to retreat when their supply train was destroyed and most of their horses and mules killed or driven off. Eventually, the Confederates had to withdraw entirely from the territory back into Confederate Arizona and then Texas. Glorieta Pass thus represented the climax of the campaign.

The Pecos Pueblo and its surrounding 341-acre area were designated a New Mexico State Monument in 1935. In 1965, it was designated a National Monument and transferred to the National Park Service. In 1991, the park was expanded to over 6,000 acres and designated as a National Historic Park.

Today, the park showcases the history of those who came before, from nomadic tribes to pithouse dwellers, the remains of the Indian pueblo and mission, the site of the Battle of Glorieta Pass, and the history of the Santa Fe Trail. The weathered adobe walls of the Spanish church share a ridge with the Pueblo ruins, which extend for a quarter mile along a ridge in a valley shared by Glorieta Creek and the Pecos River. Visitors to the park can climb down into two kivas, the ceremonial and social spaces that the Pecos Indians believed allowed them closer communion with the underworld spirits. Guided tours of the original structure of the old mission are one of the key attractions in the park. Tourists can also explore the ruins by following the self-guided trail, which leads to parts of the Pecos Pueblo, the Mission Church, and two reconstructed kivas.

The Park is also the site of the Forked Lightning Ranch House, made famous by its occupants: Tex Austin, “Daddy of the Rodeo,” oilman and rancher E.E. “Buddy” Fogelson, and his wife, actress Greer Garson. Visitors can also view the Kozlowski Trading Post, which was popular during the days of the Santa Fe Trail. On New Mexico Highway 50, the old site of Pigeon’s Ranch stands west of Pecos and the Glorieta Battlefield.

Pecos National Historical Park is 25 miles southeast of Santa Fe, New Mexico, off Interstate 25.

More Information:

Pecos National Historical Park

2 miles south of Pecos Village on Highway 63

P. O. Box 418

Pecos, New Mexico 87552-0418

505-757-7241

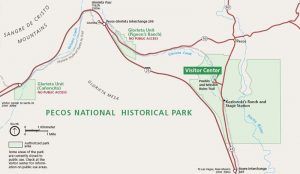

Pecos National Park Map.

From the Pecos National Park, the Santa Fe Trail made a circular bend to the north of the old pueblo, bypassing the village of Pecos. However, when Route 66 came through in 1926, the highway continued north about two miles along present-day New Mexico Highway 63 to Pecos before moving westward along present-day New Mexico Highway 50, where it rejoined the old Santa Fe Trail before continuing on past Pigeon’s Ranch and the Glorieta Battlefield.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Pre-1937 Route 66 Alignment in New Mexico

Sources:

National Park Itineraries

Pecos National Historical Park

Wikipedia