By John Esten Cooke in 1862

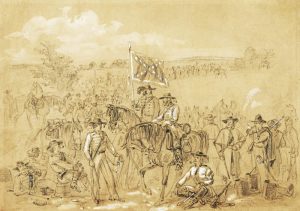

The order was given, in a ringing voice: “Form fours! Draw saber! Charge!” Now, the Confederate soldiers pursued at headlong speed, uttering shouts and yells sufficiently loud to awaken the seven sleepers! The chase exhilarated the men, the enemy just near enough to make an occasional shot practicable. Many Federal cavalrymen were overtaken and captured, and these proved to belong to the company in which Colonel Fitz Lee had formerly been a lieutenant.

The gay chase continued until we reached the Tottapotamoi, a sluggish stream, dragging its muddy waters slowly between rush-clad banks beneath drooping trees, and a small rustic bridge crossed this.

The stream line was entirely undefended by works; the enemy’s right wing was unprotected. The picket at the bridge had been quickly driven in and disappeared at a gallop, and on the high ground beyond, Colonel Lee, who had taken the front, encountered the enemy. The force appeared to be about a regiment, and they were drawn up in line of battle in the fields to receive our attack. It came without delay. Placing himself at the head of his horsemen, Colonel Lee swept forward at the pas de charge, and with shouts, the two lines came together. The shock was heavy, and the enemy stood their ground bravely, meeting the attack with the saber. Swords clashed, pistols and carbines banged, yells, shouts, and cheers resounded; then the Federal line was seen to give back and take a headlong flight.

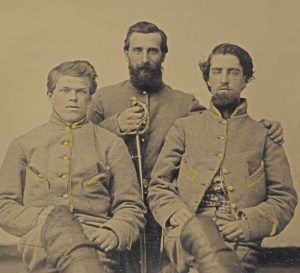

Colonel Fitz Lee.

Fitz Lee immediately pressed on and burst into the camp near Old Church, where large supplies of boots, pistols, liquors, and other commodities were found. The men speedily appropriated these, and the tents were set on fire amid loud shouts. The spectacle was animating; but a report having got abroad that one of the tents contained powder, the vicinity thereof was evacuated in almost less than no time. We were now at Old Church.

“I think the quicker we move now, the better,” I said with a laugh.

“Right,” was the reply, “tell the column to move on at a trot.”

So at a rapid trot, the column moved.

The gayest portion of the raid now began. From that moment, it was neck or nothing, do or die. We had one chance of escape against ten of capture or destruction.

Everywhere, the ride was crowded with incidents. The scouting and flanking parties constantly picked up stragglers and overhauled unsuspecting wagons filled with the most tempting stores. In this manner, a wagon stocked with champagne and various wines belonging to a General of the Federal army fell prey to the thirsty gray-backs. Still, they pressed on. Every moment, an attack was expected in front or rear.

The column was now skirting the Pamunkey River, and a detachment hurried off to seize and burn two or three transports lying in the river. Soon, a dense cloud rose from them, the flames soared up, and the column pushed on. The traces of flight were seen everywhere — for the alarm of “hornets in the hive” was given. Wagons had turned over and were abandoned — from others, the excellent army stores had been hastily thrown. This writer got a fine red blanket and an excellent pair of cavalry pantaloons, for which he still owes the United States.

Other things lay about in tempting array, but we were approaching Tunstall’s, where the column would doubtless make a charge, and to load down a weary horse was injudicious. The advance guard was now in sight of the railroad. There was no question about the affair before us. The column must cut through whatever force guarded the railroad; the guard must be overpowered to reach the lower Chickahominy. Now was the time to use the artillery and every effort was made to hurry it forward.

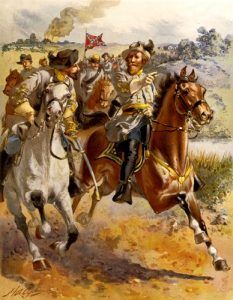

Tunstall’s was now nearly in sight, and that good fellow Captain Frayser returned and reported one or two infantry companies at the railroad. Their commander had politely beckoned to him as he reconnoitered, exclaiming in wheedling accents, full of Teutonic blandishment, “Koom yay!” But this cordial invitation was disregarded; Frayser galloped back and reported, and the ringing voice of the leader ordered, “Form platoons! Draw saber! charge!” At the word the sabers flashed, a thundering shout arose, and sweeping in a column of platoons, the gray people fell upon their blue adversaries, gobbling them up, almost without a shot. It was here that my friend Major Foote got the hideous little wooden pipe he used to smoke afterward. He had been smoking a pipe when the order to charge was given and dropped and lost it in the rush of the horsemen. He now wished to smoke and, seeing that the captain of the Federal infantry had just filled his pipe, leaned down from the saddle and politely requested him to surrender it.

“I want to smoke! “growled the Federal captain.

“So do I,” retorted Major Foote.

“This pipe is my property,” said the captain.

“Oh! What a mistake!” responded the major politely as he gently inserted the small affair between his lips. Anything more hideous than the carved head upon it I never saw.

In an hour, the column moved again. Meanwhile, a little incident happened, which still makes me laugh. A lady was living some miles off the enemy’s line whom I wished to visit, but I could not obtain the General’s consent. “It is certain to capture,” he said; “send her a note by some citizen, say Dr. Hunt; he lives near here.” I decided to do this and set off at a gallop through the moonlight for the house, some half a mile distant, looking out for the scouting parties that were probably prowling on our flanks. Reaching the lonely house outside the pickets, I dismounted and knocked at the front and back doors but received no answer. However, a dark figure was seen gliding beneath the trees, and this figure cautiously approached. I recognized the Doctor and called to him, whereupon he quickly approached and said, “I thought you were a Yankee!” and, greeting me cordially, led the way into the house. Here, I wrote my note and entrusted it to him for delivery — taking one from him to his wife within our lines. In half an hour, I rode away but, before doing so, asked for some water, which was brought from the well by a sleepy, sullen, and insolent negro. This incident was fruitful of woes to Dr. Hunt! A month later, I met him looking as thin and white as a ghost.

“What is the matter?” I said.

“The matter is,” he replied, with a melancholy laugh, “that I have been starving for three weeks in Fortress Monroe on your account. Do you remember that servant who brought you the water that night of the raid?”

“Perfectly.”

“Well, the very next day, he went over to the Yankee picket and told them that I had entertained Confederate officers and given you all the information which enables you to get off safely. As a result, I was arrested, carried to Old Point, and am just out! ”

The Chickahominy was in sight at the first streak of dawn, and we were spurring forward to the ford.

It was impassable! The heavy rains had so swollen the waters that the crossing was impracticable! Here we were within a few miles of an enraged enemy with a swollen and impassable stream directly in our front — the angry waters roaring around the half-submerged trunks of the trees — and expecting every instant to hear the crack of carbines from the rear guard indicating the enemy’s approach! The situation was not pleasing. I thought the enemy would be upon us in about an hour, and death or capture would be the sure alternative. This view was general.

The scene upon the river’s bank was curious and, under other circumstances, would have been laughable. The men lay about in every attitude, half overcome with sleep but holding their bridles and ready to mount at the first alarm. Others sat their horses asleep, with drooping shoulders. Some gnawed crackers; others ate figs, or smoked, or yawned. Things looked blue, and that color was figuratively spread over every countenance.

The column was ordered to move down the stream to where an old bridge had formerly stood. Reaching this point, a strong rear-guard was thrown out, the artillery placed in position, and we set to work vigorously to rebuild the bridge, determined to bring out the guns or die trying.

The bridge had been destroyed, but the stone abutments remained some 30 or 40 feet only apart, for the river here ran deep and narrow between steep banks. Between these stone sentinels, facing each other, was an “aching void ” necessary to fill. A skiff was procured; this was affixed by a rope to a tree in the mid-current just above the abutments, and thus, a movable pier was secured in the middle of the stream. An old barn was then hastily torn to pieces and robbed of its timbers; these were stretched down to the boat and the opposite abutment, and a footbridge was thus ready. Large numbers of the men immediately unsaddled their horses, took their equipment over, and then, returning, drove or rode their horses into the stream and swain them over. In this manner, many crossed, but the process was too slow. There, besides, was the artillery, which we had no intention of leaving. A regular bridge must be built without a moment’s delay.

Heavier blows resounded from the old barn; huge timbers approached, borne on brawny soldiers, and descending into the boat anchored in the middle of the stream, the men lifted them across. They were long enough; the ends rested on the abutments, and thick planks were immediately hurried forward and laid crosswise, forming a secure footway for the cavalry and artillery horses.

At last, the bridge was finished; the artillery crossed amid hurrahs from the men, and then the General slowly moved his cavalry across the shaky footway. A little beyond was another arm of the river, which was, however, fordable, as I ascertained and reported to the General; the water just deep enough to swim a small horse; grid through this, as through the interminable sloughs of the swamp beyond, the head of the column moved. The numerous prisoners had been marched over in advance of everything, and these were now mounted on mules, of which several hundred had been cut from the captured wagons and brought along. They started under an escort across the ford and into the swamp. They had a disagreeable time here, often mounted two on a mule; the mules constantly fell in the treacherous mud-holes and rolled their riders in the ooze. When a third swamp appeared before them, one of the Federal prisoners exclaimed, with tremendous indignation, “How many Chicken-hominies are there, I wonder, in this infernal country!”

The county’s gentlemen, we afterward heard, had been electrified by the rumor that “Stuart was down at the river trying to get across” and had built a hasty bridge for us lower down. We were over, however, and reaching Mr. Cutter’s, the General and his staff lay down on a carpet spread on the grass in the June sunshine and went to sleep. This was Sunday. I had not slept since Friday night, except by snatches in the saddle, and in going on to Richmond afterward, I fell asleep every few minutes on horseback.

By John Estes Cooke, 1862. Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

Also See: