California Miners, in front of stagecoach, 1894.

By Major Ben C. Truman in 1898

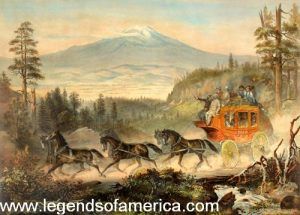

The old stage drivers of the Pacific Slope during the 1850s and 1860s, nearly all of whom had themselves been driven over the “Great Divide”, were the last of their race. Time was, however, when the man who held the ribbons over a six-horse team on the summits of the Sierra and in the canons of the Coast and Cascade Ranges was more highly esteemed than the millionaire or the statesman who rode behind him. He was, moreover, the best-liked and the most honored personage in the country through which he took his right of way. He was often a “hail fellow well met,” but he was always the autocrat of the road. His orders were obeyed with the greatest swiftness, and he was always the first to be saluted by the wayfarer, the passenger, the hostler, the postmaster, and the man at the door of the wayside inn. Our Sierra Jehu was generally an American, mainly from New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Missouri, New Hampshire, or Maine.

All, or nearly all, of his class, had been through grammar or higher schools, some of the colleges, and a majority of them had pronounced opinions on politics and theology. They could converse rationally and cleverly on all ordinary subjects.

All were gentlemanly, accommodating, and favorites with the women who lived along their routes, few of whom they addressed except by their Christian names, while the pretty, plump, 16-year-olds they would tap familiarly under their chins. Some Jehus were young and green in the service, but the majority were grim, gray, and professionally artistic. Some never indulged in liquors or wines of any kind; there were those who occasionally “spreed it,” and there were those who could not keep their teams on the grades unless they took a “couple of fingers” at every inn and “joined” the “outside traveler” moderately often between “changes.” No person ever gave a California stage driver a small coin, as one would a porter or a waiter, but a nice slouch hat, a fine pair of boots, a pair of gloves, silk handkerchiefs, or good cigars were always acceptable. These old-time drivers all dressed in good taste. Their clothes were the best fabric, made to order; their boots and gauntlets fit fine and had a good pattern, and their hats were cream-white, half stiff and half slouch. Most of them used tobacco in various forms. Many of them were perfect Apollos.

One of the best-known of all Sierra whips was “Alfred,” [George Monroe] a mulatto, who for several years, up to the time of his death, drove a stage daily between Wawona and Yosemite Valley. Probably no man, living or dead, has ever driven so many illustrious people. Grant, Garfield, Hayes, Elaine, Schurz, Sherman, Senator Stewart, Senator Morgan of Alabama, and hundreds of other Senators and Congressmen; governors of many of the States; Bull Run Russell, George Alfred Townsend, Charlie Nordhoff, John Russell Young, and scores of other eminent journalists; Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran, Tom Hill, C.D. Robinson, and other famous artists; Mrs.Langtry, Lady Franklin, Princess Louise, and many hundreds of other persons of consequence, have been taken into the great Yosemite by Alfred.

He never had an accident; always made time, either way, to a minute; knew every peak, tree, rock, canon, clearing, hut, and streamlet by the wayside. He was of medium stature and weighed 165 pounds; he dressed neatly and wore the whitest and most handsome gauntlets of any driver in the Sierra. He was melancholy, often driving the entire distance from Wawona to Inspiration Point without uttering a word or relaxing a feature. But if he had a jolly crowd behind, he would oversee his team and listen radiantly to the jokes, stories, conundrums, and conversation of those in his charge.

The last time I saw Alfred, I was a Yosemite commissioner who went over the mountains with him alone. He was wearing a new pair of gauntlets sent by Senator Morgan of Alabama and a fine whip presented by Mrs.Langtry. He said that he had never permitted anyone to take the reins from him, and that was President Grant.

“The General drove nearly to Inspiration Point,” said Alfred, “and lighted at least four cigars. He took in everything along the road and made all the turns as perfectly as an old driver. I had a fine crowd that day, the General and Mrs. Grant and Ulysses, Jr.; Mr. Young, who has since been Minister to China and is now Librarian of Congress; and there was Miss Jennie Flood, the only daughter of the wealthy bonanza man, who young Grant jilted; Miss Dora Miller, the only daughter of Senator Miller, who is now the wife of Commander Clover, United States Navy, and Miss Flora Sharon, who afterward married Sir Thomas Hesketh of England.

Miss Sharon was the prettiest girl I ever carried into the valley, and Mrs. Langtry was the most beautiful and agreeable woman. I have received presents from all the members of the Grant family. The General himself gave me a silver-mounted cigar case containing eight cigars, and the girls sent me gloves and candy.”

On August 17, 1878, I rode over one of the summits of the Sierra from Quincy, Plumas County, to Oroville, Butte County, upon the seat with “Cherokee Bill.” This driver was not an Indian but a regular Buckeye from the Western Reserve. He was a stout, clumsily put-together creature with a stub beard and drove a four-horse mud wagon.

He was more morose-looking and slovenly in his dress than most Sierra drivers, clad in overalls and woolen shirts but wearing good gloves and the regulation hat. I was the only passenger except for an old clergyman, who occupied the middle seat on the inside. We left Quincy at six in the morning, with not a cloud in the sky. At ten, the entire heavens were overcast; it began to sprinkle, and distant mutterings of thunder could be heard. At eleven o’clock, when within 1,000 feet of the summit, we encountered the full violence of the storm. I had never seen lightning, thunder, and rain like it. The rain descended not in torrents but shafts; the lightning flashed almost incessantly, and the thunders made a continuous roar, with now and then, a crash that resembled the fall of 100 or more of the noblest Conifer trees of the forest. Although thoroughly drenched, I told Bill, “I guess I’ll crawl inside.”

“No!” he replied, “you don’t want to get in with that thing; he refused to bury my poor boy a few months ago because he hadn’t been baptized. I wish one of these pines would strike him dead. He’s one of those old duffers who believes that our babies come into the world to be damned and claims that it is wicked to bury a fellow being if some old preacher like Kalloch hasn’t baptized him. I want to run him off into the canon.”

We reached the summit at noon, and a sight presented itself like I had never seen before. The storm had spent itself on the summit and swept into the stupendous chasms surrounding it with its celestial pyrotechnics and deafening artillery. We could behold the jubilee of elements below from a sunny elevation of 7,000 feet in the air. I saw Hooker’s fight in and above the clouds on Lookout Mountain at the commencement of the Atlanta campaign. I was reminded of that memorable episode by the sight before me, except that, instead of the din of small arms and the infernally demoralizing “Rebel yell,” the roar of heaven’s artillery in the Sierra on August 17 was like that of 10,000 battles in the clouds. Bill reined up so that I could stand and get a good view, at which the inside passenger stuck his head out of the window and asked:

“What is the matter, driver? What are you stopping here for? ”

Bill was ferocious and replied, “I’m listening to the salute the Almighty is firing over my poor boy’s grave.”

The preacher said no more, and I told Bill to drive on, which he did, but quietly said to me: “Do you think that preacher would ask for my certificate of baptism if he had a chance to bury me? Not much.”

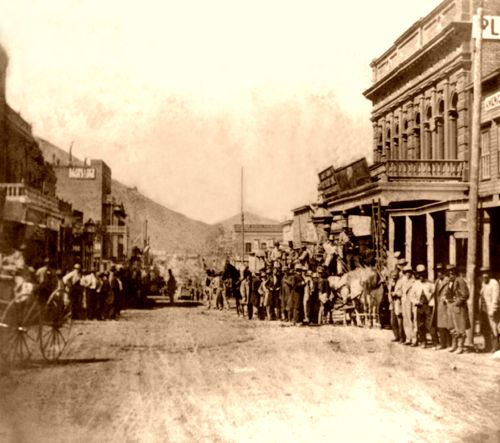

Virginia City, Nevada – Pioneer Stage is leaving Wells Fargo, owned by Lawrence and Houseworth. 1866.

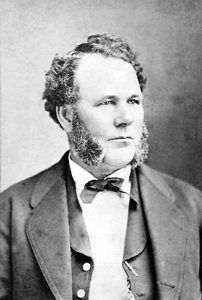

“Baldy” Green was a favorite driver in the Sierra for many years. Still, in 1866, and for a long time afterward, he drove out of Virginia City, Nevada, on the Austin Drive as far as Big Ned’s, 75 miles from Virginia City. He was nearly six feet tall, proportionately built, and was as handsome as one could wish to meet. His eyes were large, lustrous, and beautiful. His mustache was perfect. He wore a number seven boot with a hand like a woman’s. There was a sparseness of hair on his head, and he was consequently known as Baldy. To have addressed him as Mr. Green would have been as totally out of place as it would be to address Mrs. Isabella Beecher Hooker as Birdie.

He once drove Ben Holladay and the writer Horace Greeley from Virginia City to Austin, 185 miles, in 17 hours. He also let himself out thirty-odd years ago upon Vice-President Colfax and party between Big Ned’s and Virginia City, putting them over the road on one occasion forty-five miles in four hours.

He was fond of John Barleycorn and regularly took his “snifters.” Baldy Green was an accomplished juror, having judged that ambrosial decoction, known as whiskey punch.

Baldy had whips and canes and gloves and hats given him by Colfax, Richardson, Bross, Bowles, Fitzhugh Ludlow, Judge Carter, Hepworth Dixon, Captain Burton, Brigham Young, Jr., Ned Adams, John McCullough, Setchell, Senators Sharon, Fair, Stewart, and Nye, Tom Fitch, “Artemas Ward,” and Jerome Leland. He had driven Forrest, Booth, Billy Goodall, the Western Sisters, Susan and Kate Denin, Billy Birch, Ben Cotton, Sher Campbell, Jerry Bryant, Barry Sullivan, Starr King, Talmage, Bishop Kip, Horace Greeley, “Yankee” Sullivan, John C. Heenan, Barrett, and scores upon scores of eminent men and women representing all professions and pursuits.

“Artemas Ward,” said Baldy, “was the funniest man I ever had on the seat with me, and dear Ned Adams the jolliest. We sang and drank, told stories, and laughed all the way. Mark Twain has ridden with me, but I never liked him. He seemed to study a long time before he said anything funny. And he never gave me a cigar or asked me to take a drink in his life. Joe Goodman was a good fellow. Jim Nye could rattle off stories all day. Tom Fitch was always broke. Ben Holladay was the most profane man I ever knew. Johnny Skae always sent me a new hat or some gloves, but they never reached me. Bill Stewart never said turkey to anyone. General Winters and General Avery were generous to a fault.

“Doctor Talmage once rode with me and said he could see God in all the treetops. ‘Do you drink?’ he thundered in my left ear one night. I thought sure he was going to pull out a flask. But he didn’t. He just said: ‘ You shouldn’t.’ Then he pointed to a new moon and said: ‘There’s no water in that moon.’ And I just hazarded the reply that there was a lucky crowd up there, and then he opened his mouth like a cavern and shouted, ‘Ha!’ so loudly that my team came near running away.

But, that man Starr King was a glorious person. The music of his voice still lingers in my ear. Charley Forman was a generous fellow; everybody liked him. I tell you, John McCullough was a pleasant chap who could get away with many drinks between drinks. Heller went out of Virginia with me once, and every once in a while, he would take an egg from under my nose or from the tip end of my glove. And once he took hold of my nose as if to blow it and let fall from it, it seemed, about a dozen half dollars, which he rubbed together and then out of sight between his hands and then took them out of my hat. Ah, those happy times will never come again.”

Short, stout, jolly Billy Hamilton is known as one of the oldest and best drivers on the Pacific Coast and a man who has owned stage lines in many parts of Oregon, Nevada, and California. He could handle the “ribbons” with any of them for thirty years and commenced staging in 1850. For many years, he owned the lines from Colfax to Grass Valley, Los Angeles to Bakersfield, Mojave to Independence, and many others. Billy was fond of his “tod” when not driving. For 25 years, he made more money than he knew what to do with, and he threw it away. He was generous to a fault and has loaned more twenty-dollar gold pieces that he could never get back than you could put in a peck measure.

I have ridden with Billy in the Sierra, through the Mojave Desert, and over the Coast Range, and I consider him one of the most delightful whips in the world. He weighs 190 pounds and is 65 years old. Although he has struck bed-rock pretty closely several times, he was often helped out by Leland Stanford and Charles Crocker (who never went back on any of the forty-niners who had done them a service) and now owns a pretty ranch in Kern County where he resides when he is not at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, playing “cinch ” for half bottles of Extra Dry.

Stagecoach Driver.

Buffalo Jim, laid to rest at Merced in 1881, was a well-known Yosemite driver 20 years ago but had sometimes driven from Portland, Oregon, to Tucson, Arizona. I came down from the Valley with him once when his only other passengers were two women from Los Angeles, two children, and an Eastern clergyman. Jim was accounted a good driver, but upon the occasion referred to, there was something concerning with the wheel horse (he was driving only four horses), which he attempted vainly to discover. The animal acted worse and worse for about a mile when, at last, it commenced to buck and kick and finally broke into the dashboard. At this, the team started on the run, and Jim put down the brake as far as he could and yanked the team with all his might. His hat flew off, and we went like the wind. The horses all kicked and ran, and I saw him getting worn out and scared. However, I could have helped him if he had permitted me (the two women were my wife and sister and their children). I know the peculiarities of these fellows and would not offer assistance but merely said to those inside in answer to their questions:

“The team is running away, but don’t jump!”

As we happened to be on a smooth, broad piece of road with no big rocks or trees, I felt that the team would run itself tired and that the stage would not be turned over if the harness and brake held and it did not leave the grade. After a run of four miles, Jim handed me the lines over the wheelers, saying:

“Do your best, old man, for I am about gone up!”

The harness was getting shaky, and two of the traces had given away, but the under-gear, the brake, and the lines remained all right, and we soon struck a stretch of deep sand and at last brought up the team within a few hundred yards of a swing station, which we managed to reach in bad condition. Jim was limp and fatigued, so much so that he could not swear properly. We all drew long breaths, although none inside realized the closeness of the call we had just had on that mountain grade.

Hill Beechey, who died at the age of 60, 16 years ago at Elko, Nevada, was a crack driver away back in the fifties and was known all over the Pacific Coast. He was short and stout and weighed 200 pounds. He owned many stage lines in California, Nevada, Oregon, and Idaho and died wealthy. He made himself famous by capturing and bringing to justice the murderers of Lloyd Magruder, a Marylander, and four others, who were killed by three cold-blooded ruffians while returning from some Idaho mining camps with $100,000 in gold in 1863.

One of the best-known Sierra drivers is “Mr. Church,” for nearly 30 years, has driven from Truckee to Lake Tahoe in the morning and back in the evening from May until October. It is a 14-mile drive up from Truckee to Tahoe.

Mr. Church makes the up trip in about four hours and the return in about three. This is one of the most delightful short drives on the continent. The air is pure and invigorating, and the summer sunbeams play hide-and-go-seek in the snowdrifts, which may be seen all the way. The warmest days are tempered by the breezes that chase each other from the snowbanks in the Sierra canons, which consistently linger in the “lap of summer.” Then you have the Truckee River with you all the way — that matchless mountain stream of pure, ice-cold water. Tree, brush, and flower stand up perfectly on either side and a little bird, with a throat like a thrush, warbles sweet canticles from Truckee to Tahoe. There are often quail, grouse, and deer to be seen, and twenty years ago, it was not infrequent that a grizzly blocked the way. Mr. Church is a married man and has a fascinating family in Truckee. He has carried many thousand people up the Truckee River and has never had an accident. He is a stout, powerfully built man of about five feet ten and is sixty years old. He is temperate in everything, smoking one or two choice cigars each way and taking a good horn at the end of each trip. He has never been sick or intoxicated in his life. He knows every tree and rock on the road and could make all the turns blindfolded. He is as gentle as a young maid and invariably sees to it before he starts that wagon, seats-under gear, pole, single-trees, double trees, and harness are in good order. He always carries an ax, oil, wrench, rope, and washers and is ready for any emergency after the agent says, “All set!”

Stagecoach driver Eli “Pop” Church in front of the Truckee Hotel (The Whitney House), late 1800s.

Mr. Church has received an endless number of presents in the way of hats and gauntlets, as he has driven hundreds of such liberal men like Leland Stanford, William M. Stewart, Newton Booth, John P. Jones, Jim Fair, John W. Mackey, Captain Kohl, Charlie Felton, Charlie Crocker, Dan Freeman, Jim Ayers, Duke Gwin, Dick Oglesby, Tom Scott, Colonel Forney, Rlaine, Burlingame, Joe Lynch, George Francis Train, Lord Lorne, and Arthur Sullivan.

The last time I saw Mr. Church, he was ecstatic over what he considered the event of his life. He had been carrying President and Mrs. Hayes up the Truckee to Tahoe.

“Mrs. Hayes was such a sweet, pretty woman,” said Mr. Church; “I knew she was a person of rigid temperance principles, and so I told her about the ice-cold water she should have where I watered my team. Then, suddenly, it occurred to me that all there was to drink from was an old oyster can, and I would have given a month’s salary for a nice cup. I broke the matter gently to her, and she said she would rather drink from a tin can at such a place than from a White House glass or cup. But when we reached the place, even the tin can was gone. I just wanted to die right then and there. In my confusion, I fell over a rock and took a back seat in my mind. I also took about ten or 15 minutes longer than usual to water my team, hoping that someone from Tahoe would come with a can, a cup, or something to drink from. Still, at last, I was compelled to tell Mrs. Hayes that the can had been taken away or had fallen into the river. And then I dipped up some water and rinsed the bucket, as I often do, and then dipped up some more and drank from it. And just as soon as I set it down, Mrs. Hayes said, ‘I must have some of that delicious water, and I want it out of that bucket.’

“I nearly had the staggers. Was it the wife of the President of the United States who had said this, or had I suddenly become crazy? Well, I dipped up a third of a pail full, and she took it up, as I had done, and drank from it, and then the President and all the other passengers followed suit, and then we all laughed and had a good time over it. Ah, she was a nice, well-bred, lovely woman. I can see her now drinking out of that bucket. But out of respect for Mrs. Hayes and her husband, no horse or human being has ever drunk out of that bucket since. Mrs. Church and I consider it the most precious thing in our house next to our children.”

This driver was always addressed as “Mr. Church. ” Although I have known him for nearly 30 years and ridden with him many times, I have never known his Christian name or heard him nick-named.

The most notorious whip of the Sierra and the most sought after by Pacific slope trotters for many years was Hank Monk, who died about ten years ago, aged fifty. And while he was no slouch of a driver, he had never been considered strictly first-class or reliable. But, he stumbled into great notoriety as the man who drove Horace Greeley over the Sierra Nevada Mountains from Carson City to Placerville 30-odd years ago. In 1886, I was in Placerville and stopped at the same inn where Mr. Greeley had stayed overnight. The landlord informed me, in speaking of that drive, that the canvas top of the wagon was torn in two or three places, that Mr. Greeley’s hat was knocked in, that the team was white with foam, and that the stage and harness, and driver were covered with dirt and mud. Hank Monk was somewhat under stature, wore no whiskers, and lacked the robust-dandy way of many Sierra drivers.

Upon returning to New York, Mr. Greeley sent Monk a gold English hunting case, lever watch and chain, and a pleasant letter. Subsequently, believing that Monk was blamable for the many ridiculous stories told of him connected with his ride, he let go of his meager appreciation for the driver who took him from Carson City to Placerville on time.

Once, Governor of Nevada, Henry Kinkead, told me one day in 1881, while Monk was driving us from Glenbrook to Carson: “Hank is greatly overrated as a stage driver. I know scores of better ones. But his getting Horace Greeley over the Sierra and down into Placerville ‘on time’ gave him great notoriety. It was a dreadful drive, and that it didn’t kill the old editor was no fault of Monk’s. The road was slow and rough, and Hank was full of tarantula juice when he left Carson. Hank was thirty-eight years old. In the goodness of Greeley’s heart, he presented Hank with a gold watch, which he has often pawned, sold, and managed to get back. But there were so many ridiculous exaggerations and right up and down falsehoods told of that ride that Greeley became very ‘tired.’ In reply to a request of Hank, some twenty years ago, for some favor, Horace wrote: “I would rather see you 10,000 fathoms in hell than ever give you a crust of bread, for you are the only man who ever had the opportunity to place me in a ridiculous light, and you villainously exercised that opportunity, you damned scamp!”

The old story, which has been accepted as the true one and which will bear retelling, is that Monk realized that he was compelled to land Mr. Greeley at Placerville at a particular time and had determined to carry out his instructions, notwithstanding the bad condition of the grade, and whoever has ridden alone in a mud-wagon down a mountain at the rate of eight or nine miles an hour need not be informed of the affliction of the occupant during, or his appearance at the end of, the ride. As the old story goes, Monk rattled along at a terrific gait, making sharp curves on two wheels at one time and the next, whirling within an inch of a precipice. The grand old journalist, statesman, and philosopher had all he could do to hold on and occasionally pleaded with the driver to take it a little easier, but he, in his wild Western way, answered: “Keep your seat, Horace; I’ll get you there on time.” This same old coach was on exhibit at the Midwinter Fair in San Francisco and made hourly trips through the grounds between the Forty-nine Mining Camp and the Administration building.

Next to Hank Monk, the most widely known and most notorious Jehu on the Pacific Coast, was Clark Foss, who drove over the St. Helena Mountain from Calistoga to the Geysers, a distance of twenty-five miles, it being sixty-eight miles by boat and train from San Francisco to Calistoga, part of the route being through one of the most exquisite valleys in the world, with sweeps of vineyards and orchards, and grain lands for more than 30 miles on either side, walled in by spurs of the Coast Range called the Napa Mountains on the right and the Sonoma Mountains on the left.

Clark Foss was six feet, two inches tall, big correspondingly, and weighed 260 pounds. He owned a hotel six miles from Calistoga, where his passengers took dinner, a dinner that had never been excelled at a wayside inn. There was always lamb, chicken, game, fresh and preserved fruits, numerous vegetables, the nicest desserts, coffee, tea, milk, buttermilk, and pure mountain water. Mrs. Foss, who will be loved and remembered by all who ever knew her, had charge of this never-to-be-forgotten accessory. “Old Foss,” as he was called ten years preceding his death, to distinguish him from his big boy, Charlie, was a lineal descendant of the son of Nimshi, who, as is well known, drove furiously down the grades of Samaria. Thirty years ago, Old Foss was undoubtedly the most reckless stage driver on the Pacific coast. Before making the trip down the steep northern side of the mountain, he would chain the hind wheels and then whip the team into a startling canter, and the person who went with Clark Foss to the Geysers took his life in his hands.

And, it was not until he had killed and injured several persons and at last turned over his stage and broken 14 bones in his own body that he concluded that there was no fun in whipping his team down the un-graded side of a mountain. A few thousand dollars’ damages ticketed him on the road to good sense.

So, after his recovery, he settled up and built a splendid grade, and no person was injured afterward. He was one of the roughest men in the state, and few dared to oppose him or be so blunt as he. He neither drank nor smoked. But he could swear until everything looked blue. He was a gentle husband and father, but everything except Mrs. Foss had to get out of his way. He could hold, direct, start, and stop his team with his voice. I had sat on the box with him when he had a six-horse team on the canter when he would shout, ” Down!” and the whole team would come into a trot, and then he would shout, “Way down, now!” and every animal would come to a dead stop. Again, when his team would be approaching a nice long level stretch between his inn and Calistoga, he would shout, “Shake’era up now!” and every horse would break into a run, which I thought was impossible to check. But he would check them without touching the brake or reining them up in less than a minute. Still, he was generally considered an unsafe driver, and his business fell off so largely a few years before his death that he had to send for his son Charlie, who was driving over Yosemite Road at the time.

Charlie Foss has no superior in the world, probably in his line. He grew up as a driver among the Coast Mountains, spent several years in Southern California and Arizona, and graduated in the Sierra. He is nearly as tall as his father, being more than six feet, but only weighs 190 pounds. He is temperate in everything and one of the gentlest and most polite fellows I have ever known. He drives from the Geysers to Fossville, returns 35 miles every day of his life, and has never had an accident or breakdown. America has no prettier grade, and the entire drive is picturesque and beautiful. I have sat alongside Charlie as he drove down the last grade into that Plutonian Paradise at a speed of ten miles an hour, where the curves were so short that many a time, I could not see the leaders. He never stops at an inn and does not minutely examine the harness, brakes, and other parts of the wagon. When he takes his seat, he always asks: “Are you all ready, ladies and gentlemen?” or, “Is everybody ready?” He invariably halts at the summit, where he sees a landscape with few superiors. Mountains, valleys, orchards, and villas may be seen for 100 miles when the atmosphere is clear and rare. Pines, redwood, oaks, laurel, spruce, fir, manzanita, and madrono stand up behind the lush grasses and herbs that embroider the enchanting way, and here, and there are silvery streamlets that go gurgling away down to the sparkling Pacific, which may be seen at intervals sixty miles away. All is enlivened by the notes of birds, the scamper of game, and the ineffable fragrance of aromatic trees and bush and flowers.

Buck Jones, a gray-headed forty-niner, drove in Sierra and Yuba Counties for many years. He was an entertaining fellow and used to delight in telling how Governor F. F. Low once drove a dray in Marysville, how ex-Lieutenant Governor Johnson and Creed Haymond tended bar in a mining camp on the South Fork of the Yuba, and where and why George C. Gorham and James G. Fair were called the two slippery gentlemen from Slipperyville. This old driver had once mined at Bidwell’s Bar and had paid as high as seventy-five cents for an onion and a dollar for a pound of pork. “I saw a gambler take out his pistol and shoot down another gambler,” he once said to me, “in cold blood, and then go and help hang a horse thief for the good of the camp.” But Buck might have been drawing the longbow in this one instance.

By Major Ben C. Truman in 1898, compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

About the Author: This article, Knights of the Lash: Old Time Stage Drivers of the West Coast, was written by Major Ben C. Truman and appeared in the Overland Monthly, Volume XXXI, January-June 1898. Truman was an American journalist, author, and distinguished war correspondent during the Civil War. He wrote numerous books, including several on California history, and for a time, even worked in public relations for the State of California. He died in 1916. *Note: This article is not verbatim, as corrections and editing have occurred.

Also See:

Adventures in the American West