By William Francis Bailey in 1906

Grading was commenced in July 1864 and track-laying in the spring of 1865. The start was not promising. The line was initially located directly west of Omaha, Nebraska, but after $100,000 had been spent, it was abandoned because of the hills and consequent heavy grades. Then, two new lines were surveyed, one to the north and then west and the other south nearly to Bellevue, Kansas, and then west. This latter was called the “Ox-bow Route” and was finally selected by the company, notwithstanding violent opposition by the people of Omaha, who feared that the company would cross the Missouri River at Bellevue, thus leaving Omaha out.

September 25, 1865, saw 11 miles finished, and in November, an excursion was run from Omaha to the end of the track, 15 miles.

This was gotten up by Vice-President Durant, who took an engine and flat car, inviting about twenty gentlemen to go with him on the first inspection trip to Sailing’s Grove. Among the excursionists was General William Sherman, who gloried in the undertaking and expressed regret that, at his age, he could hardly anticipate living until the completion of the work. The party was very enthusiastic, and as the narrator naively puts it, “as the commissary was well supplied, the gentlemen enjoyed themselves.”

For several reasons, the work dragged on. It took one year to complete the first 40 miles. The lack of rail connections east of Omaha was, previous to January 1867, when the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad reached Council Bluffs, Iowa, at high expense and delay. The work was new, those in charge were not experienced at that time, funds were scarce, and the company’s credit was not yet established. As a result, the average rate of progress during the first 12 months was only a mile a week.

“The work was military in character, and one is not surprised to find among the superintendents and others in charge a liberal sprinkling of military titles. A detachment of soldiers always accompanied surveying parties as a protection against Indians. The construction trains were amply supplied with rifles and other arms, and it was boasted that a gang of track-layers could be transmuted into a battalion of infantry at any moment. Over half of the men had shouldered muskets in many a battle.”

The following extract from a newspaper of that day brings out the same facts.

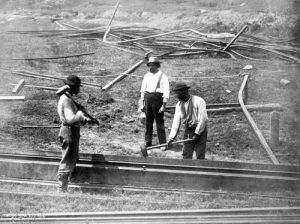

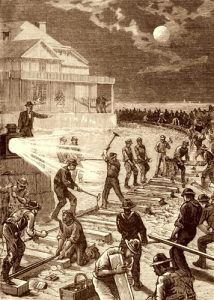

“The whole organization of the road is semi-military. The men who go ahead (surveyors and locators) are the advance guard; following them is the second line (the graders), cutting through the gorges, grading the road, and building the bridges. Then comes the army’s main body, placing the ties, laying the track, spiking down the rails, perfecting the alignment, ballasting and dressing up, and completing the road for immediate use. Along the line of the completed road are construction trains pushing ‘to the front’ with supplies. The advance limit of the rails is occupied by a train of long box-cars with bunks built within them, in which the men sleep at night and take their meals. Close behind this train come trainloads of ties, rails, spikes, etc., which are thrown off to the side. A light car drawn by a single horse gallops up, is loaded with this material, and then is off again to the front. Two men grasp the forward end of the rail and start ahead with it, the rest of the gang taking hold two by two until it is clear of the car. At the word of command, it is dropped into place, right side up, during which a similar operation has been going on with the rail for the other side, — thirty seconds to the rail for each gang, four rails to the minute. As soon as a car is unloaded, it is tipped over to permit another to pass it to the front, and then it is righted again and hustled back for another load.

“Close behind the track layers comes the gaugers, then the spikers and bolters. Three strokes to the spike, ten spikes to the rail, 400 rails to the mile. Quick work, you say, — but the fellows on the Union Pacific are tremendously in earnest.”

Or, as another writer said, “We witnessed here the fabulous speed with which the line was built. Through the 200 or 300 miles beyond were scattered ten to fifteen thousand men in great gangs preparing the road-bed with plows, scrapers, shovels, picks, and carts, and among the rocks, with drills and powder, were doing the grading as rapidly as men could stand and move with their tools. Long trains were brought up to the end of the track, loads of ties and rails the former were transferred to teams, sent one or two miles ahead, and put in place on the grade. Spikes and rails were reloaded on platform cars and pushed up to the last previously laid rail. With an automatic movement and celerity that was wonderful, practiced hands dropped the fresh rails one after another on the ties exactly in line.

Hugh sledges sent the spikes home, — the car rolled on, and the operation was repeated, while every few minutes, the long heavy train behind sent out a puff of smoke from its locomotive and caught up with its load of material the advancing work. The only limit to the rapidity with which the track could thus be laid was the power of the road behind to bring forward material.”

The above description applies to the later construction period when the forces had become thoroughly organized and the work systematized. The following table shows the rate of construction:

| Ground was broken at Omaha | December 2nd, 1863 |

| Work commenced at Omaha | Spring, 1864 |

| 11 Miles completed to Gilmore | September 25th, 1865 |

| 40 Miles completed to Valley | December 31st, 1865 |

| 47 Miles completed to Fremont | January 24th, 1866 |

| 50 Miles completed | March 13th, 1866 |

| 100 Miles completed | June 2nd, 1866 |

| 247 Miles completed to the 100th Meridian | October 5th, 1866 |

| 305 Miles completed | December 31st, 1866 |

| 414 Miles completed to Sidney, Wyoming | August 1867 |

| 516 Miles completed to Cheyenne, Wyoming | November 13th, 1867 |

| 573 Miles completed to Laramie, Wyoming | May 9th, 1868 |

| 745 Miles completed | December 31st, 1868 |

| 1033 Miles completed to Ogden, Utah | March 8th, 1869 |

| 1086 Miles completed: | |

| To Promontory, Utah | April 28th, 1869 |

| Formal connection made | May 10, 1869 |

| Regular train service commenced | July 15th, 1869 |

| Completed according to Judicial decision | November 6th, 1869 |

The progress made was wired East daily and published in the principal newspapers. Thus, in the Chicago Tribune, items such as “One and nine-tenth miles of track laid yesterday on the Union Pacific Railroad” appeared in every issue.

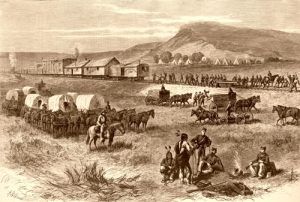

During the line’s construction, headquarters were established at different points at the front, which were used as a basis of operations to construct the section beyond. These places enjoyed a temporary boom; some of them, like Jonah’s Gourd, to wither up and die away, while others profiting by the start are today’s points of importance. The first of these was North Platte, Nebraska; its selection was caused by the delay in bridging the river. This was the road’s terminus during the fall of 1866 and up to June 1867. During this time, it was the distributing point for all the country West. With more or less money, the mixture of railroad laborers, freighters, etc., inaugurated a rough time and began the wild scenes that attended the line’s construction. During the winter, the town had a population of 5,000 and over 1,000 buildings.

With the completion of the line to Sidney, Wyoming, in June 1867, the rough element left and established themselves at that point, leaving at North Platte about 300 of the more sedentary, law-abiding class who had determined on that point for their home. When moving to the front, houses were torn down, and cars were loaded on to be taken to the new site and re-erected.

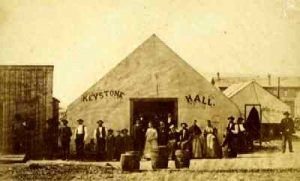

When it was known that Cheyenne was to be the terminus for the winter of 1867-1868, there was a grand hegira of roughs, gamblers, and prostitutes from all along the line and the East. The population jumped to 6,000. Dwellings sprang up like mushrooms. They were of every conceivable character. Some were simply holes in the ground roofed over, known as “dugouts,” others of canvas, while some were of wood and stone. Town lots were sold at fabulous prices. The only pastimes were gambling and drinking. Shooting scrapes with “a man for breakfast” were an everyday occurrence, and stealing was so common that there was no comment on occasion. It is said of old Colonel Murrian, the then Mayor of Cheyenne, that he advanced the City’s script 18¢ on the dollar by inflicting a fine of ten dollars on those who “made a gunplay,” i.e. shot at anyone,– and that it was his custom to add a quarter to the fines he inflicted, making them $10.25 or $25.25, with the explanation that his was dry work. The extra quarter was to cover the stimulant his arduous duties required.

Such conditions brought about an uprising by the more respectable element. Vigilance committees with “Judge Lynch” in command took hold, and from his Court, there was neither appeal nor stays. Witnesses were not held to be essential. The toughs were known, and the judgments of the Court were generally correct. At least the defendants were not left in a condition to make a complaint or appeal. During the first year of its existence, the Vigilance Committee hung or shot twelve of the desperadoes and was instrumental in sending as many more to the Penitentiary. The effect was to compel the tough element to either leave or abide by the laws and to put the decent element in control.

The next headquarters was in Benton, Wyoming. In two weeks (July 1868), a city of 3,000 inhabitants sprang up as if by the touch of Aladdin’s Lamp.

It was laid out in regular squares, divided into five wards, had a Mayor and Board of Aldermen, a daily newspaper, and a volume of ordinances for the City Government. It was the end of the freight and passenger service and the beginning of the division under construction. Long trains arrived from and departed for the East twice daily, while stages and wagon trains connected it with points in Idaho, Montana, and Utah. All the passengers and goods for the West came here by rail and were re-shipped to their several destinations.

Twenty-three saloons paid licenses to the city, while dance halls and gambling dens were even more numerous. The great institution was the “Big Tent.” This frame structure, 100 feet long and 40 feet wide, was floored for dancing, to which and gambling it was entirely devoted.

A visitor to the city thus described it: “One to two thousand men and a dozen or more women were encamped on the alkali plain in tents and shanties.” Only a small proportion of them had aught to do with the road or any legitimate occupation. Restaurant and saloon keepers, gamblers, desperadoes of every grade, and the vilest of men and women made up this “Hell on Wheels,” as it was most aptly termed. Six months later, all that was left to mark the site were a few rock piles, half-destroyed chimneys, and piles of old cans. After a tumultuous existence of only 60 days, the city had “got up and pulled its freight” to the next headquarters.

Green River, Bryan, Bear River City, and Wasatch were the headquarters successively. The first, owing to the railroad, had made it the end of a division and located shops there, has survived; the other three are but memories.

At Bear River City, the tough element that had been driven out of the different points East congregated in large numbers, proposed to make a stand, and was supposed to become a permanent town. The law-abiding element numbered about 1,000, the toughs as many more. Three thugs were hung for murder, and in reprisal, the town was attacked on November 19, 1868, by the tough element. They seized and burned the jail, then sacked and destroyed the plant of the “Frontier Index,” a printing outfit that followed up the railroad, issuing a Daily Paper, and which had been particularly outspoken in its denunciation of the lawless element. They then proceeded to attack some of the stores but were met by the townspeople and badly defeated in the pitched battle that ensued. They made an undignified retreat, leaving 15 of their number dead in the streets. From then on, the tough element fought shy of the city, and with the road’s extension, its business left. Today, nothing indicates that a town of 4,000 or 5,000 had ever stood there.

The tough element started to make Rawlins one of the “Hells,” but the decent element had had enough and proceeded to clean up the town — showing they proposed to stand no foolishness.

The last railroad town was Wasatch, located at the eastern end of the longest tunnel (770 feet) on the road. In fact, the delay occasioned by this work gave rise to the town. When the line was put down, a temporary track was built around the obstruction to permit the track’s materials to reach the front. This place initially had a machine shop, roundhouse, and eating station, all of which were removed to Evanston in 1870.

Upon the passage of the supplementary Charter in 1864, the restriction confining the Central Pacific to the State of California was withdrawn. They were authorized to build 150 miles east of the California boundary. This latter restriction was also withdrawn by Congress in 1866, leaving the meeting point to be determined by the rapidity of the construction of the respective lines, or as the Act of Congress put it, they could locate, construct, and continue their line until it should meet the Union Pacific continuous line.

With the experience of three years behind them and the Land Grant, Government Bonds, and prospective earnings, not to speak of the element of pride ahead, the two lines entered into a race that had never been seen. The rivalry extended from the Presidents of the respective Companies down to the boy who carried water to the graders. Both forces, justly proud of their achievements, considered themselves a little better than the other. One form of the rivalry was how the outfit could get the most significant amount of track down in one day. The Union Pacific’s forces led off six miles; soon after, the Central went them a mile better.

Then, the Union Pacific Railroad put down seven and a half miles; the Central Pacific forces, not to be outdone, announced they could get down ten miles in one working day. Vice-President Durant offered to wager $10,000, but it could not be done, and the Central Pacific outfit resolved it should be done. Waiting until there were but 14 miles for them to lay, they started in and laid ten miles and 200 feet from seven A.M. to seven P.M., using 4,000 men in the operation.

And then the Union Pacific outfit was mad. They claimed that if they had massed their forces, made special preparations, etc., they could do better than their competitors, but they could not prove it because there was no more track to lay.

The Central Pacific people ran their grade east to Echo Canon when their completed line was only built near Wadsworth, Nevada. The Union Pacific Railroad located its line to the California State line and had its graders at work as far west as Humboldt Wells, Nevada, 460 miles west of Ogden.

However, this line west of Promontory was never built, and it is said that one million dollars was expended in this way. The Central Pacific had their grade established some eighty miles east of Promontory Point, thirty miles east of Ogden, and this was when the Union Pacific was laying their completed track within a mile of and parallel to their grade. The prize was so great that every nerve was strained between contestants as to who should push their track further. The advantages were about equal.

The Central Pacific was somewhat nearer their base of supplies; their laborers were the quiet, orderly, and easily managed Chinese, and then they were in comparatively good financial shape. The Union Pacific, though farther from their base of supplies, were in railroad communication with the points of manufacture; their men, while turbulent and hard to control, were enthusiastic and worth three to one of the opposing forces. They were well paid, well housed, and well-fed and were handled by men who had, as a rule, army experience back of them and who certainly were “bosses” in the best and fullest sense.

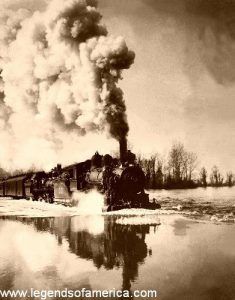

During the winter of 1868-1869, the advantage was with the Central Pacific Company. Snow sheds fully protected their line across the Sierras and only met with one week’s suspension of business from snow troubles during the whole winter. Simultaneously, the Union Pacific Railroad was blocked between Cheyenne and Green River for four months. The rate of construction grew rapidly. During 1864, about 200 men were employed on the grading and track-laying. While it took one year to complete the first 40 miles, the second year, the year 1865, saw 265 miles done, over a mile a day working time, and this was exceeded from that on.

There were about 2,500 graders employed in 1867 and 450 track-layers, and from this number up until the completion of the road. Their forces numbered 12,000 men and 3,000 teams, while 600 tons of material were placed daily during the spring of 1869 when the contest was at its height. The maximum track laid in one day was seven and a half miles. As the line progressed, roundhouses were put up at Omaha, North Platte, Cheyenne, Laramie, and Ogden, each having 20 stalls, and at Grand Island, Sidney, Rawlins, Bitter Creek, Medicine Bow, and Bryan, of 10 stalls each. These were substantial brick or stone buildings with sheet-iron roofs that were thoroughly fireproof.

In addition to the large shops at Omaha, where much of the equipment was built, repair shops were built at Cheyenne and Laramie.

Stations were established at an average of 14 miles apart. The station buildings were built of wood and two classes, three-fourths of them 25 by 40 feet, the remaining one-fourth 36 by 60 feet. At each station, water tanks were erected and surmounted by windmills. Sidings 3,000 feet long were located at each station and, in some cases, at points intermediate 1,500 feet long. In all, about 6% of the mainline distance was in sidetracks.

To accommodate the Public and its employees, the Company built large hotels at North Platte, Cheyenne, Laramie, and Rawlins.

Eating houses were established at Grand Island, North Platte, Sidney, Cheyenne, Laramie, Rawlins, Bryan (Near Granger long ago passed out of existence), Wasatch (afterward removed to Evanston), and Ogden. During construction days, the charge for a meal was $1.25, but with the road’s opening, this was reduced to one dollar and then to the present price of 75¢.

By William Francis Bailey, 1906. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Author & Notes: This tale is adapted from a chapter of William Francis Bailey’s book The Story of the First Trans-Continental Railroad: Its Projectors, Construction, and History, published in 1906 by the Pittsburgh Printing Co. The tale is not 100% verbatim, as minor grammatical errors and spelling have been corrected.

Also See:

Historical Accounts of American History