By John Moody in 1919

The United States, as we know it today, is essentially the result of mechanical inventions, mainly agricultural machinery and the railroad. One transformed millions of acres of uncultivated land into fertile farms, while the other furnished the transportation that carried the crops to distant markets. Before these inventions appeared, it is true, Americans had crossed the Alleghenies, reached the Mississippi Valley, and had even penetrated the Pacific coast; thus, in a thousand years, the United States might conceivably have become a far-reaching, straggling, loosely jointed Roman Empire, depending entirely upon its oceans, internal watercourses, and imperial highways for such economic and political integrity as it might achieve. But the great miracle of the 19th century — the building of a new nation, reaching more than 3,000 miles from sea to sea, giving sustenance to more than one hundred million free people, and diffusing among them the necessities and comforts of civilization to a greater extent than the world had ever known before is explained by the development of harvesting machinery and the railroad.

The railroad originated from applying two fundamental ideas: using a mechanical means to develop speed and employing a smooth-running surface to minimize friction. Though these two principles are combined today, they were initially distinct. There were railroads long before there were steam engines or locomotives. If we seek the natural predecessor of the modern railroad track, we must go back 300 years to the wooden rails drawn by the little cars used in English collieries to carry the coal from the mines to tidewater. The natural history of this invention is clear enough. The driving of large coal wagons along the public highway made deep ruts in the road, and some ingenious person began repairing the damage by laying wooden planks in the furrows. The coal wagons drove over this crude roadbed so successfully that particular proprietors started constructing notable planked roadways from the mines to the river mouth. Logs forming what we now call “ties” were placed crosswise at three or four feet intervals, and thin “rails,” likewise of wood, were laid lengthwise upon these supports.

So effectually, this arrangement reduced friction so that a single horse could now draw a great wagon filled with coal — an operation which two or three teams, lunging over muddy roads, formerly had great difficulty performing. A thin sheet of iron was laid upon the wooden rail to lengthen the life of the road. The next improvement was increasing the wagons’ durability by making iron wheels. It was not until 1767, when the first rails were cast entirely of iron with a flange at one side to keep the wheel steadily in place, that the modern roadbed appeared in all its fundamental principles. This was only two years after Watt had patented his first steam engine and nearly 50 years before Stephenson built his first locomotive. The railroad was as completely dissociated from steam propulsion as the ship. Just as vessels had existed for ages before the introduction of mechanical power, the railroad had been a familiar sight in the mining districts of England for at least two centuries before Watt’s invention gave it wings and turned it to broader uses. In this respect, the railroad’s progress resembles that of the automobile, which had existed in a crude form long before the invention of the gasoline engine, making it practically useful.

In the United States, three new transportation methods emerged almost simultaneously: the steamboat, the canal boat, and the railcar. Of all three, the last was the slowest in attaining popularity. As early as 1812, John Stevens of Hoboken, New Jersey, aroused much interest and more amused hostility by advocating building a railroad across New York from the Hudson River to Lake Erie instead of a canal. For several years, this tenacious spirit journeyed from town to town and State to State in a fruitless effort to push his favorite scheme. The great success of the Erie Canal was finally hailed as a conclusive argument against all the ridiculous claims made in favor of the railroad. It precipitated a canal mania that spread all over the country.

Yet the enthusiasts for railroads could not be discouraged, and presently, the whole population was divided into two camps: the friends of the canal and the friends of the iron highway. Newspapers acrimoniously championed either side; the question was a favorite topic among debating societies; public meetings and conventions were held to promote one transportation method and denounce the other. The canal, it was urged, was not an experiment; it had been tested and not found wanting; already, the outstanding achievement of De Witt Clinton in completing the Erie Canal had made New York City the metropolis of the Western world. The railroad, it was asserted, was just as certainly an experiment; no one could tell whether it could ever succeed; why, therefore, pour money and effort into this new form of transportation when the other was a demonstrated success?

It was simple to find fault with the railroad; it has always been its fate to arouse the farmers’ opposition. This hostility emerged early and was primarily based on grounds that still resonate today. They said the railroad was a natural monopoly; no private citizen could ever hope to own one; it was thus a kind of monster that, if encouraged, would override all popular rights. From this economic criticism, the railroad’s enemies moved on to construction details: the rails would be washed out by rain; mischievous people could destroy them; they would snap under the cold of winter or be buried under snow for a considerable period, thus stopping all communication. The champions of artificial waterways would point in contrast to the beautiful packet boats on the Erie Canal, with their fine sleeping rooms, their restaurants, their spacious decks on which the fine ladies and gentlemen assembled every warm summer day, and would insist that such kind of travel was far more comfortable than it could ever be on railroads. To all these pleas, the railroad advocates had one unassailable argument–its infinitely greater speed. After all, it took a towboat three or four days to go from Albany to Buffalo, and the time was not far distant; they argued when a railroad would make the same trip in less than a day. Indeed, our forefathers made a curious mistake: they predicted the speed of the railroad to be 100 miles an hour, which it has never consistently attained with safety.

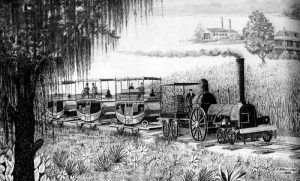

If the American of today could transport himself to one of the first railroad lines built in the United States, it is not unlikely that he would side with the canal enthusiast in his argument. The rough pictures, which accompany most accounts of early railroad days, showing a train of omnibus-like carriages pulled by a locomotive with a vertical boiler, represent a somewhat advanced stage of development. Although Stephenson had demonstrated the practicability of the locomotive in 1814 and the American John Stevens had constructed one in 1826, demonstrating its ability to negotiate curves, local prejudice against this innovation remained firm. The farmers asserted that the sparks set fire to their hayricks and barns, and that the noise frightened their hens so that they would not lay eggs, and their cows could not give milk.

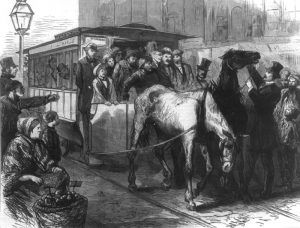

Therefore, almost any other propulsion method was preferred on the earliest railroads. Horses and dogs were used, winches turned by men were occasionally installed, and in some cases, cars were fitted with sails.

Of all these methods, the horse was the most popular: he sent out no sparks, carried his fuel, made little noise, and would not explode. His only failing was that he would leave the track, and to remedy this defect, the early railroad builders hit upon a happy device. Sometimes, they would fix a treadmill inside the car; two horses would patiently propel the caravan, the seats for passengers being arranged on either side. So unformed was the prevalent conception of the ultimate function of the railroad, and so pronounced was the fear of monopoly that, on specific lines, the roadbed was laid as a state enterprise, and the users furnished their own cars, just as the individual owners of towboats did on the canals. The drivers, however, were an exceedingly rough lot; no schedules were observed, and as the first lines had only single tracks and infrequent turnouts when the opposing sides would meet each other coming and going, precedence was usually awarded to the side with the stronger arm. The roadbed showed a slight improvement over the mine tramways of the 18th century, and the rails were only long wooden stringers with strap iron nailed on top. The country’s resources were so undeveloped that the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad builders petitioned Congress in 1828 to remit the duty on the iron that it was compelled to import from England. The trains consisted of a string of little cars, with the baggage piled on the roof, and when they reached a hill, they sometimes had to be pulled up the inclined plane by a rope. Yet traveling in these earliest days was probably more comfortable than in those immediately following the general adoption of locomotives. When, five or ten years later, the advantages of mechanical as opposed to animal traction led to the introduction of engines on a large scale, the passengers behind them rode through the constant smoke and hot cinders that made railway travel an incessant torture.

Yet the railroad speedily demonstrated its practical value; many of the first lines were highly profitable, and the hostility they had received soon changed to an enthusiasm that was just as unreasoning. The speculative craze, which invariably follows a discovery, swept over the country in the thirties and the forties and manifested itself most unfortunately in the new Western States — Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan. Here, bonfires and public meetings fueled the enthusiasm; people believed that railroads would not only immediately open the wilderness and pay the interest on the bonds issued to construct them, but also become a source of revenue for the sadly depleted state treasuries.

Much has been heard of government ownership in recent years. Yet, it is nothing particularly new, for many of the early railroads in these new Western States were built as government enterprises, with frequently disastrous results. This mania, accompanied by land speculation, was primarily responsible for the panic of 1837. It led to the repudiation of debts in particular States, which gave American investments an evil reputation abroad for many years.

However, railroad building had a comparatively solid foundation in the more settled parts of the country. Yet the railroad map of the forties indicates that railroad building in this early period was incoherent and haphazard.

Practically everywhere, the railroad was an individual enterprise; the builders had no further conception of it than as a line connecting two given points, usually a short distance apart. The roads of those days began anywhere and ended almost anywhere. A few miles of iron rail connected Albany and Schenectady.

There was a road from Hartford to New Haven, Connecticut, but none from New Haven to New York. A line connected Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with Columbia; Baltimore had a road to Washington; Charleston, South Carolina, had a similar connection with Hamburg in the same State. By 1842, New York State, from Albany to Buffalo, possessed several disconnected stretches of railroad. It was not until 1836, when work began on the Erie Railroad, that a plan was adopted for a single line extending several hundred miles from an obvious point, such as New York, to an equally obvious destination, such as Lake Erie. Even then, a few farsighted men could foresee when the railroad train would cross the plains and the Rockies and link the Atlantic and the Pacific. Yet, in 1850, nearly all the railroads in the United States lay east of the Mississippi River, and all of them, even when they were physically mere extensions of one another, were separately owned and separately managed.

As successful as many railroads were, they had hardly yet established themselves as the preeminent means of transportation. The canal had lost in the struggle for supremacy, but with these constructed waterways, particularly the Erie, flourishing with little diminished vigor. The river steamboat had enjoyed development in the first few decades of the 19th century, almost as great as the railroad itself. The Mississippi River was the great natural highway for the products and the passenger traffic of the South Central States; it had made New Orleans, Louisiana, one of the largest and most flourishing cities in the country and, indeed, the prosperous cotton planter of the fifties would have smiled at any suggestion that the “floating palaces” which plied this mighty stream would ever surrender their preeminence to the rusty and struggling railroads which wound along its banks.

This period, considered the first in American railroad development, ended in the middle of the century. It was an era of significant progress, but not one of absolute assured success. A few lines earned handsome profits, but the railroad business was not favorably regarded in the main, and railroad investments everywhere were suspected. The condition in many railroads is illustrated by the fact that the directors of the Michigan & Southern Railroad, when they held their annual meeting in 1853, had to borrow chairs from an adjoining office because the sheriff had taken their own for debt. Even a railroad with such territory as the Hudson River Valley extending from New York to Albany existed in a state of chronic dilapidation, and the New York and Harlem, which had an entrance into New York City as an asset of incalculable value, was looked upon merely as a vehicle for Wall Street speculation.

Meanwhile, the increasing traffic in farm products, mules, and cattle from the Northwest to the plantations of the South created a demand for more ample transportation facilities. In the decade before the Civil War, various north and south railway lines were projected, and some of these were assisted by grants of land from the Federal Government. The first of these, the Illinois Central, received a substantial land grant in 1850 and ultimately reached the Gulf at Mobile by connecting with the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, which had also received federal grants for assistance. However, the panic of 1857, followed by the Civil War, halted all railroad enterprises. In 1856, approximately 3,600 miles of railroad had been constructed; by 1865, only 700 miles had been laid down. The war disrupted the Southern railroads, and the North and South lines lost all but local traffic.

After the war, a rapid recovery began, bringing to the fore the first of the great railroad magnates and the shrewdest business geniuses of the day, Cornelius Vanderbilt. Though he had spent his early life and laid the basis of his fortune in steamboats, he was the first to appreciate that these two transportation methods were about to change places — that water transportation was to decline. Rail transportation was to gain ascendancy. It was about 1865 that Vanderbilt acted on this farsighted conviction, promptly sold out his steamboats for what they would bring, and began buying railroads even though his friends warned him that, in his old age, he was wrecking the fruits of a complex and thrifty life. However, Vanderbilt perceived what most American businessmen of the time failed to see: a significant shift had occurred in the railroad situation following the Civil War.

The period from approximately 1860 to 1875 marks the second stage in the railroad development of the United States. The characteristics of this period were the development of the great trunk lines and the construction of a transcontinental route to the Pacific. The Civil War ended the Mississippi River’s supremacy as the primary transportation route of the West. The fact that this river ran through hostile territory — Vicksburg did not fall until July 4, 1863 — forced the farmers of the West to find another outlet for their products. By this time, the country from Chicago and St. Louis eastward to the Atlantic ports was fairly completely connected by railroads. The necessities of war led to significant improvements in construction and equipment. The business, which had previously declined, began to thrive; New Orleans ceased to be the region’s primary industrial port, and the business relocated to St. Louis and Chicago.

Yet, though this significant change in traffic routes took place during the war, consolidating the various small railroads into great trunk lines did not begin until after peace had been assured. Establishing five great railroads extending continuously from the Atlantic seaboard to Chicago and the West was perhaps the most remarkable economic development of the ten or 15 years succeeding the war. By 1875, these five great trunk lines —the New York Central, Pennsylvania, Erie, Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and Grand Trunk —had connected their scattered units and established complete through systems.

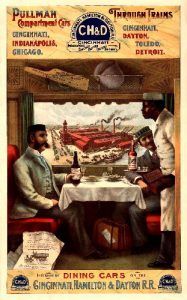

All the vexations that had necessarily accompanied railroad traffic in the days when each one of these systems had been a series of disconnected roads had disappeared. The grain and meat products of the West, accumulating for the most part at Chicago and St. Louis, now came rapidly and uninterruptedly to the Atlantic seaboard, and railroad passengers, no longer submitting to the inconveniences of the Civil War period, began to experience for the first time the pleasures of railroad travel. Together with the articulation of the routes, significant mechanical changes and reconstruction programs completely transformed the American railroad system. The former haphazard character of each road is evidenced by the fact that, in the Civil War days, there were eight different gauges, resulting in almost impossible use of the rolling stock of one line on another. However, a few years after the Civil War, the standard gauge of 4 feet 8 1/2 inches had become uniform throughout the United States.

The malodorous “eating cribs” of the 1850s and 1860s—small station restaurants located at select spots along the line—began to disappear, and the modern dining car emerged. The old, rough-and-ready sleeping cars began to give place to the modern Pullman. One of the most significant drawbacks to antebellum travel was the absence of bridges across great rivers, such as the Hudson and the Susquehanna.

At Albany, for example, the passengers in the summertime were ferried across, and in winter, they were driven in sleighs or were sometimes obliged to walk across the ice. It was not until after the Civil War that a great iron bridge, 2,000 feet long, was constructed across the Hudson at this point. On the trains, the little flickering oil lamps now gave place to gas, and the wood-burning stoves–frequently in those primitive days smeared with tobacco juice–in a few years were displaced by the new heating method, by steam.

The accidents, which had been almost the prevailing rule in the fifties and sixties, were significantly reduced by the Westinghouse air brake, invented in 1868, and the block signaling system introduced somewhat later. In the ten years following the Civil War, the physical appearance of the railroads underwent a significant transformation; new and larger locomotives were introduced, and the freight cars, which during the Civil War had a capacity of approximately eight tons, were now built to carry 15 or 20 tons.

The former, little, flimsy iron rails were taken up and relaid with steel. In the early seventies, when Cornelius Vanderbilt substituted steel for iron on the New York Central, he had to import the new material from England. Almost all American railroads were single-track lines during the Civil War, which limited the capacity for extensive traffic. Vanderbilt laid two tracks along the Hudson River from New York to Albany and four from Albany to Buffalo, two exclusively for freight and two for passengers. By 1880, the American railroad, in all its essential details, had arrived.

However, during the same period, even more sensational developments occurred. Soon after 1865, the American railroad builder’s imagination reached far beyond the old horizon. Until then, the Mississippi River had marked the Western railroad terminus. Now and then, a road straggled beyond this barrier for a few miles into eastern Iowa and Missouri. The enormous territory from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean was crossed only by the old trails. The one thing that perhaps did the most to facilitate the construction of the transcontinental road was the annexation of California in 1848. One year later, the wild rush on the discovery of the goldfields led Americans to realize that on the Pacific coast, they had an empire that was great and incalculably rich but almost inaccessible.

The loyalty of California to the Northern cause in the war naturally stimulated a desire for closer contact. In the ten years preceding 1860, Congress constantly brought to the attention the importance of a transcontinental line. The project sparked considerable jealousy between the North and the South, as each region sought to control its eastern terminus. This impediment no longer stood in the way; early in his term, therefore, President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill authorizing the construction of the Union Pacific — a name doubly significant as marking the union of the East and the West and also recognizing the sentiment of loyalty or union that this great enterprise was intended to promote. The building of this railroad and that of the others ultimately made the Pacific and the Atlantic coasts near neighbors. These included the Santa Fe, Southern Pacific, Northern Pacific, and Great Northern. Here, it is sufficient to emphasize that they achieved the concluding triumph in what is undoubtedly the most extensive system of railroads in the world. These transcontinental roads completed the work of Columbus. He sailed to discover the western route to Cathay, but a mighty continent blocked his path. But the first train that crossed the plains ascended the Rockies and reached the Golden Gate, assured a rapid and uninterrupted transit westward from Europe to Asia.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Penetrating The Pacific Northwest

Railroads & Depots Photo Gallery

About the Author: John Moody wrote The Railroad Builders, A Chronicle of the Welding of the States in 1919. A Century of Railroad Building is the first chapter of the book.