By Jim Hinckley

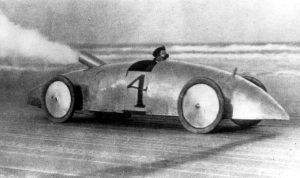

Louis Ross racing in the twin-engined Stanley ‘Woogle-Bug’ steam automobile – Daytona Beach, Florida, 1903.

The history of the American automobile during the first decades of the 20th century is, to say the very least, interesting. There were business leaders who created vast empires that viewed the future of the automobile with a sense of optimistic pessimism. There were visionaries whose attempts to transform the world with imaginative innovation were hampered by extreme myopia.

There were also dreamers and charlatans, eccentrics, and intellectual giants. For good measure, the auto industry during this period was also amply sprinkled with men whose genius bordered on insanity.

Together, they transformed the world at unprecedented speed. Together, they unleashed previously unimagined individual freedom while enslaving the masses.

In the beginning, the automobile was a blank canvas for mechanical artisans. In those halcyon days, it held the promise of utopia, a world filled with labor-saving devices and laughter-filled adventures on roads yet to be built.

From the perspective of the dawning of the second decade of the 21st century, it is difficult to imagine an America without automobiles, highways, car payments, pollution, service stations, and family vacations. It may be even harder to imagine an era when the automobile was such a wonder that it received top billing over the fat lady and albino at the Barnum & Bailey Circus, and astute businessmen such as Montgomery Ward saw the automobile as a fad that children should see before it passed.

To provide a bit of perspective on how the development of the automobile and related infrastructure transformed America and the world, consider what took place in the three decades between 1900 and 1930. In the closing years of the 19th century, during the nation’s first automobile race, drivers were collapsing from exhaustion after wrestling their automobiles over 20 miles of the 50-mile course. By 1904, people were driving from coast to coast.

In 1909, American industry produced more than 828,000 horse-drawn vehicles using technologies little changed in a century. Meanwhile, other factories or shops produced just over 125,000 automobiles.

Twenty years later, in 1929, a mere 4,000 horse-drawn vehicles were manufactured, but the number of automobiles produced had surpassed 1,000,000. Now, imagine what this meant to businesses such as livery stables and blacksmiths, harness makers, and wheelwrights.

Studebaker, the world leader in the manufacture of horse-drawn vehicles in 1890, was one of the nation’s top ten automobile manufacturers in 1929. William Durant, the founder of General Motors, employed Charles Nash as a cushion stuffer at the Flint Wagon Works in the 1890s and as the president of Buick shortly before World War I.

By 1925, few aspects of American society were left unscathed by the automobile. More families owned automobiles than had indoor plumbing. Introduced by GM, the installment plan had been adopted by other industries, launching an unprecedented consumerism-based society and previously unknown levels of personal debt.

Farmers prospered from the expanded markets made possible by automobiles and trucks. They were also set free from a world of isolation as trips to town were no longer measured in days.

Organized labor propelled industries to provide factory workers with previously unimagined wages and an opportunity to emulate the wealthy, who had two days per week to pursue leisure. The Sunday drive and the family vacation spawned an explosion in the development of tourism-related industries. Even the American lexicon was transformed with words such as motel.

America’s youth found other ways to embrace the freedom unleashed by the automobile, much to the detriment of currently acceptable societal norms. They also became adept shade tree mechanics and self-taught mechanical engineers, an often overlooked component in the Arsenal of Democracy during World War II.

In 1919, the world’s first tricolor traffic signals were installed on the streets of Detroit, Michigan. In 1929, the first cloverleaf interchange opened in Woodbridge, New Jersey.

In 1912, Cadillac proved it was the standard of the world with the introduction of new models that featured an electric starter and electric lights as standard equipment. It was the death knell for electric vehicles that dominated the urban landscape and for steam-powered cars that had stunned the world with previously unimaginable speed records.

In 1919, Essex became the first low-priced, mass-produced enclosed sedan with fixed tops and roll-up windows. Yet, it would be 1947 before heaters became a factory-installed option for Chevrolet trucks.

Customers could order the optional heated steering wheel on the 1918 McFarland. Meanwhile, Henry Ford and other manufacturers published full-page advertisements claiming brakes on the front wheels were dangerous.

In luxury cars of the late 1920s, the pampered and wealthy enjoyed the luxury of an optional radio to provide a theme song for the adventure on the open road. But, incredibly, it would be the late 1950s before some manufacturers offered turn signals as standard equipment.

The first automobile recall occurred in 1921 when Chevrolet introduced a trouble-prone air-cooled model that almost served as the company’s swan song. The genius behind the debacle was Charles Kettering, the man who developed the electric starter for Cadillac, Freon for refrigeration, Duco automotive paints, and leaded gasoline that enabled the manufacture of high-compression engines.

By 1925, the consumer was besieged with a staggering array of model choices produced by an equally staggering array of manufacturers. The options available or that were standard equipment were even more bewildering.

It was an age of astounding technological development. The limited production, steam-powered Doble offered unparalleled luxury and mind-numbing speeds (0 to 70 in nine seconds for a 4,500-pound roadster).

However, the buyer of a new Ford received a wooden measuring stick that he inserted in the gasoline tank under the front seat cushion to determine fuel levels. Other manufacturers offered a modern type fuel gauge coupled to an electric sending unit, but these were mounted on the gas tank at the rear of the car.

By the close of World War I, customers could choose between four-cylinder models or V-8 engines (even in a Chevrolet), hybrids or steamers, electrics, or two-cylinder cyclecars. A dozen years later, they could, if they had the money, even select models with 12 or 16-cylinder models or turbocharged eight-cylinder behemoths. Yet some manufacturers steadfastly held to the belief that brakes on the front wheels represented a danger, and others clung to the belief that mechanical brakes were safer than hydraulic systems.

In two short decades, America became an automobile-obsessed nation. Yet within three decades, the automobile had become the nation’s cornerstone.

A century later, the automobile is the scapegoat, a necessary evil. It is viewed as a tether keeping mankind from that long-promised utopia where the lion lies with the lamb and the skies are not cloudy all day.

My, how times change.

©Jim Hinckley, Legends Of America – September 2013, updated May 2025.

About the Author: Jim Hinckley is an award-winning author and photographer who is an official contributor to Legends Of America through a partnership developed in October 2012. He is a former Associate Editor of Cars and Parts Magazine and the author of multiple books, including several on Route 66. You can follow him on Jim Hinckley’s America.

Also See: