Marion County Courthouse, Yellville, Arkansas. Courtesy Wikipedia.

Though most feuds in the Old West seemed to center on land and water rights, the Arkansas Tutt-Everett War, also known as the King-Everett War and the Marion County War, was born of politics. Starting with political ambition, the feud raged from 1844 to 1850, with increasing violent confrontations and, in the end, the deaths of some 14 people.

The Arkansas legislature created Marion County in 1836. The Tutts, who were associated with the Whig Party, and the Everetts, part of the Democratic Party, were at odds. The two sides repeatedly clashed as they competed for electoral offices and control of the county.

When the county was formed, the Everetts already lived there and controlled the vast majority of the law and authority in the area. Originally from Kentucky, the family comprised tall, powerful men, including John, Cimmeron “Sim,” Jesse, and Bart.

In the meantime, the Tutts, who lived in Searcy County and controlled most of the area politics, were not necessarily pleased when portions of the county were given over to provide for the “new” Marion County.

The Tutts and the Kings supported the now-defunct Whig Party.

The Tutts, originally from Tennessee, settled in the community of St. Joe. Headed by father R.B. Tutt, who had three sons, Ben, Hansford “Hamp,” and David Casey, the family was known as gamblers and horse racers and had a fondness for drinking and fighting. Hamp owned a grocery store and saloon, the only public house in the county, which was a popular spot for the whiskey drinkers of the region.

The King family also lived in the area, comprised of brothers “Old Billy,” James, Hosea, and Solomon. Though the brothers never got caught up in the feud, Billy’s and Hosea’s sons did, including Billy’s offspring, Jack, Loomis, and Dick, and Hosea’s sons, Bill and Tom. James had no children. Whig Party promoters, the Kings, quickly aligned themselves with the Tutts. Voter preference had little to do with the ideas of either party but more about what a person could get away with if “their man” was in office. As a result, elections quickly became heated.

At the time, there were approximately 300 voters in the county. In no time, almost every resident aligned with one side or the other in contests that led to increasingly violent confrontations. Amid rising tensions, a public debate was held in Yellville in June 1844, which soon erupted into a violent brawl among the spectators. It was this event that started what became known as the Tutt-Everett War. Not using guns in this fight, the participants used their fists, rocks, and anything else they could handle. Only after one of the Tutt followers, a man named Alfred Burnes, struck “Sim” Everett in the head with a hoe and, thinking he killed him, did the melee settle down. As Sim lay prone, Burnes made a quick retreat. Though there was plenty of bloodshed during the frenzy, Sim was not killed, and there were no serious injuries. However, afterward, both sides began to always walk around armed, and a series of lawsuits were filed that would last for years.

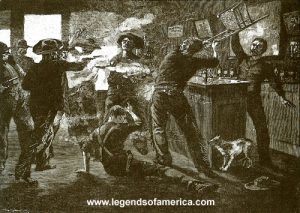

Saloon gunfight.

Periodically, gunplay and alcohol-fueled fistfights became the norm, further increasing the ill will of the county. The feud came head-on on October 9, 1848, when a shootout erupted before a town meeting in Yellville. When the smoke cleared, several men were dead, including Sim Everett. Two days later, the Everetts and their supporters ambushed the Kings, killing “Old Billy and his son, Lumus. Young Billy King and another man, who went by the nickname of “Cherokee Bob,” were seriously wounded but could still escape.

By the following summer, things were getting so out of control that the current sheriff, Jesse Mooney, who was not affiliated with the feuding factions, planned on “laying down the law.”

On July 4, 1849, he and Constable Adams deputized several men, making plans to “clean up the county.” In the meantime, the Tutt faction was gathering in the saloon, and the Everetts and their supporters were taking cover behind a building across the street. Before Mooney even got a chance to finish with the newly “deputized” citizens, a gunfight erupted that lasted the entire afternoon. Even after all the ammunition was exhausted, the two factions continued to fight, using sticks, bricks, rocks, knives, and anything else that could harm them.

Ten men, including Jack King, Bart, and Sim Everett, Davis, Ben, and Lunsford Tutt, were dead when the dust had cleared. More were wounded. Dave Sinclair, a friend of the Tutts and the alleged killer of Sim Everett, rode out of town right after the fight. However, a posse of Everett’s friends found him the following day and shot him.

When Jesse Everett, who was in Texas during the gunfight, heard of the deaths of his brothers, he quickly returned to Arkansas to avenge their killings. Though he allegedly made several attempts at assassinating Hamp Tutt, he was unsuccessful. With general mayhem in the county, Sheriff Mooney sent his son Tom to Little Rock to ask for help from the governor. Though the young man successfully requested the aide, he never returned to Marion County. After several weeks, the carcass of his horse washed up at the mouth of Rush Creek, but Tom’s body was never found.

In September 1849, Arkansas Governor John Sheldon Roane sent General Allan Wood to Marion County to investigate and order the militia if necessary.

Seeing the apparent lawlessness in the area, General Wood raised the militia in Carroll County, who marched in and relieved Sheriff Mooney of his duties.

Governor Roane ordered that the Everetts and their supporters be arrested. Soon, several men were arrested, and martial law lasted in the county for six weeks. However, once winter arrived, the troops were removed, and within weeks of their departure, Everett supporters broke their friends out of jail.

The following year, in September 1850, Hamp Tutt was shot and killed. Soon, the remaining Everetts moved on.

The conflict was the only great family feud ever known in Arkansas history.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, March 2025.

Also See:

Jaybird Woodpecker War of Texas

The Slicker War of Benton County, Missouri

See Sources.