Taos Pueblo – 1,000 Years of History

The Mountain Song of Taos – or The Taos Hum

Taos, New Mexico, is the county seat of Taos County, situated in the north-central part of the state, surrounded by the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The town derives its name from the native Taos language, meaning “place of red willows.” Its long history dates back hundreds of years, and today, it proudly incorporates three cultures—Native American, Anglo, and Hispanic—into a vibrant city with a rich heritage of diverse people.

The Taos Valley, with its two great Pueblos, the old town of Fernando de Taos, and the even more ancient settlement known as Ranchos de Taos, is one of the most fascinating historical sites in the West.

Most of Taos County’s eastern boundary is occupied by the Taos Range of the Rocky Mountains, and Taos Valley is one of the most picturesque. On the east, it is surrounded by a half-moon of mountains, with no foothills extending into the mesas to diminish the scene’s grandeur. Eleven streams from these mountains cross the valley in a westerly direction, and the Rio Grande cuts through it in a 500-foot-deep canyon.

Before European explorers discovered the region, it had been inhabited as early as 12,000 BC. Early inhabitants roamed the area, hunting large mammals, such as mammoths, and gathering wild foods for subsistence. By 3,000 BC, the people began to adopt the idea of agriculture from their neighbors in Mexico, which led to restrictions on their movements and the development of long-term communities.

The ancestors of the Pueblo people, commonly known as the Anasazi, were the first permanent inhabitants of Taos Valley. Room blocks and pit houses in the Taos area testify to their presence since 900 A.D. Around 1200 A.D., they aggregated into small above-ground structures of 50-100 rooms. The current Taos Pueblo was probably built between 1300 and 1450 A.D.

Throughout its early years, Taos Pueblo was a central trade point between the native populations along the Rio Grande and their neighbors to the northwest, the Plains Tribes. The Taos Pueblo hosted a trade fair each fall after the agricultural harvest. This fair impressed the first Spaniards who made contact with the ancient pueblo. Eventually, trade routes would link Taos to the northernmost towns of New Spain and Mexico’s cities via the famed Chihuahua Trail.

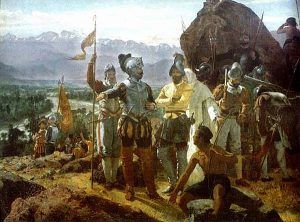

The first Spanish visitors to Taos Pueblo arrived in 1540 as members of the Francisco Vásquez de Coronado expedition, which stopped at many of New Mexico’s pueblos searching for the rumored Seven Cities of Gold. At the time, Hernando de Alvarado described the pueblo as having adobe houses built close together and stacked five or six stories high. The homes became narrower as they rose, with each level’s roofs providing the floors and terraces for those above. Surrounded by a low defensive wall, the community had two main clusters of buildings, one on each side of the Rio Grande, which provided water for the residents and their crops.

Juan de Onate.

The first Spanish-influenced architecture appeared in Taos Pueblo after Fray Francisco de Zamora came there in 1598 to establish a mission under orders from Spanish Governor Don Juan de Onate.

The village of Taos, originally called Fernando de Taos, was established around 1615, following the Spanish conquest of the Indian Pueblo villages by Geneva Vigil. Initially, the relations of the Spanish settlers with the Taos Pueblo were amicable. Still, resentful meddling by missionaries and demands for a tribute to the church and Spanish colonists led to several revolts. Taos would become the center of many of the Pueblo rebellions against the Spanish, the first of which almost occurred in 1609 when Governor Don Juan de Onate was accused of throwing a young Taos Indian from a rooftop. However, Onate was soon removed from office. Another minor revolt was quickly subdued in 1613. But these small insurgencies did not stop the determined Spanish priests and colonists. Around 1620, the first Catholic Church in the pueblo, San Geronimo de Taos, was constructed.

Reports from the period indicate that the native people of Taos resisted the church’s building and the imposition of the Catholic religion. Throughout the 1600s, cultural tensions grew between the native populations of the Southwest and the increasing Spanish presence. In 1631, another event occurred in the rebellion of the Spaniards when a resident missionary and the soldiers who escorted him were attacked and killed. Tensions continued to grow, and in 1640, the Taos Indians killed their priest and several Spanish settlers and fled the pueblo. The people would not return to their pueblo for over two decades in 1661.

In the 1670s, a drought swept the region, causing famine among the pueblos and provoking increased attacks from neighboring nomadic tribes. Due to the number of attacks, the Spanish soldiers could not always defend the pueblos. At about the same time, European-introduced diseases ravaged the pueblos, significantly decreasing their numbers. Becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the Spanish, the Puebloans turned to their old religions, provoking a wave of repression from the Franciscan missionaries. While the missionaries had previously tended to ignore the occasional Pueblo ceremonies as long as the people made some effort to attend mass, the Puebloans’ renewed vigor towards their religions caused Fray Alonso de Posada to forbid Kachina dances by the Pueblo Indians and ordered the missionaries to seize every mask, prayer stick, and effigy they could lay their hands on and burn them. Furthermore, the Indians were forbidden, on pain of death, to practice their native religions. When some Spanish officials tried to curb the Franciscans’ power, they were charged with heresy and tried before the Inquisition.

In 1675, the tension came to a head when Governor Juan Francisco Trevino ordered the arrest of 47 medicine men and accused them of practicing witchcraft. Four of the men were sentenced to be hanged – three of those sentences were carried out, while the fourth prisoner committed suicide. The remaining men were publicly whipped and sentenced to prison. When this news reached the Pueblo leaders, they moved in force to Santa Fe, where the prisoners were held. Because many Spanish soldiers were away fighting the Apache, Governor Trevino released the prisoners. Among those who were released was a medicine man from the San Juan Pueblo (now known as Ohkay Owingeh) named Pope, who would soon become the leader of the Pueblo Rebellion. Pope then moved to Taos Pueblo and began plotting with men from other pueblos to drive the Spaniards out.

Before long, in August 1680, a well-coordinated effort of several pueblo villages was established. Throughout the upper Rio Grande basin north of El Paso to Taos, the Tewa, Tiwa, Hopi, Zuni, and other Keresan-speaking pueblos, and even the non-Pueblo Apache, planned to rise against the Spanish simultaneously.

On August 10, 1680, the attack, known as the Pueblo Revolt, was commenced by the Taos, Picuri, and Tewa Indians in their respective provinces against 40 Franciscans and another 380 Spaniards, including men, women, and children. The Spaniards who escaped fled to Santa Fe and the Isleta Pueblo, one of the few pueblos that did not participate in the rebellion. Pope’s warriors, armed with Spanish weapons, then besieged Santa Fe, surrounding the city and cutting off its water supply. Barricaded in the Governor’s Palace, New Mexico Governor Antonio de Otermín soon called for a general retreat. On August 21, the remaining 3,000 Spanish settlers streamed out of the capital city and headed for El Paso, Texas. Believing themselves to be the only survivors, the refugees at the Isleta Pueblo also left for El Paso in September. In the meantime, the Pueblo people destroyed most of the Spanish homes and buildings. The Taos Indians again destroyed San Geronimo and killed two priests.

After the Spanish Reconquest of 1692, the Taos Pueblo continued armed resistance against the Spanish until 1696, when Governor Diego de Vargas defeated the Indians at Taos Canyon. He soon persuaded the Taos Pueblo Indians to drop their arms and return from the mountains.

In 1723, the Spanish government forbade trade with the French and limited trade with the Plains Tribes only to Taos and Pecos, thereby giving rise to the annual summer trade fairs at those locations where Comanche, Kiowa, and others came in significant numbers to trade captives for horses, grain, and trade goods from Chihuahua.

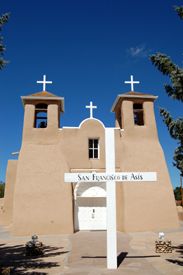

In 1776, at the time of the American Declaration of Independence, there were an estimated 67 families with 306 Spaniards in the Taos Valley. At that time, the Ranchos de Taos area was the most populous. The first Spanish church was built in Ranchos de Taos that same year. A few years earlier, the first church in the area was built in 1772. The Franciscans supervised the construction of the historic San Francisco de Assisi Mission Church, which was finally completed in 1816.

During the 1770s, Taos was repeatedly raided by the Comanche, who lived on the plains of eastern Colorado. Juan Bautista de Anza, governor of the Province of New Mexico, led a successful punitive expedition in 1779 against the Comanche.

San Francisco de Assisi Mission Church in Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico, still

serves a congregation today. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

The construction of the church at Fernando de Taos began in 1796, but it was not completed until 1806. The ancient church at the Pueblo, which was destroyed during the Taos Revolt in 1847, served as the headquarters of the Roman Catholic diocese. Spanish/native relations within the pueblo became amicable briefly as both groups found a common enemy in the invading Ute and Comanche tribes. However, resistance to Catholicism and Spanish culture was still strong. Even so, Spanish religious ideals and agricultural practices subtly infiltrated the Taos community, essentially beginning during this period of increased cooperation between the two cultural groups.

Between 1796 and 1797, the Don Fernando de Taos Land Grant gave land to 63 Spanish families in the Taos Valley. A more formal settlement was established to the northeast of Ranchos de Taos, with a fortified plaza and adobe buildings surrounded by residential areas. Homes were built in large quadrangles that offered a fortress-like structure. Hostile raiding Indians from outside the Taos area were thwarted in their attempts to enter the village. Sentries stationed at the corners of the fortified village kept vigil day and night. A massive gate offered the only means of entry and exit to the Plaza. The enclosure served as a refuge for livestock at night, and merchants used the area to display their wares during trade fairs.

Taos was, for many years following the American occupation, the chief political center of the Territory’s storm. The presence there of such men as Charles Bent, the first Governor; Colonel Christopher “Kit” Carson, the famous scout, and guide; Colonel Ceran St. Vrain, the well-known merchant; “Don Carlos” Beaubien, one of the original proprietors of the notorious Maxwell Land Grant and the first Chief Justice of New Mexico; Father Martinez, a demagogue, traitor, conspirator against peace and as great a rascal as ever, who remained un-hanged in New Mexico, whether viewed from a political or moral standpoint — such individuals as these gave the community a position in Territorial affairs equal to that of Santa Fe, the capital.

Along with these famous names, dozens of other French, American, and Canadian trappers were operating in Taos County. A brisk fur trade began, bringing yet another element — the mountain men — to the Taos trade fair. By then, the Taos Valley was well populated with livestock, agriculture, and people who supplied Mexico with inexpensive goods. Goods also came into Taos, such as the first printing press west of the Mississippi River, which was established in 1834 to print books for the co-educational school founded by Padre Antonio Jose Martinez. In 1835, the padre began printing the first newspaper, El Crepusculo, which would later become the predecessor to The Taos News. In 1840, some 20,000 Rio Grande wool blankets were exported south to Mexico.

In 1842, Padre Martínez, after giving him instruction, baptized Kit Carson as a Catholic so that he could marry Josefa Jaramillo. The following year, Kit and Josefa married, and Kit purchased a house from the Jaramillo family as a wedding present for his new bride. The house, built in 1825, served as Carson’s home until 1868; today, it is the Kit Carson Home and Museum. Three years later, in 1846, Colonel Stephen W. Kearny, with his “Army of the West,” occupied New Mexico for the United States. Charles Bent of Taos was appointed as the first American Governor. That same year, business remained brisk in Taos, as 1.7 million dollars in beaver and other furs were traded through the town.

New Mexico formally became a territory of the United States in 1847 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. However, many of the native Mexicans and Indians were not happy with this event. The Mexicans in the Taos area resented the newcomers and enlisted the Taos Indians to aid them in an insurrection. Mexican Pablo Montoya and Tomasito, a leader of the Taos Pueblo Indians, led a force of Mexicans and Indians who did not want to become a part of the United States. Charles Bent, the new American governor who was headquartered at Taos, was killed and scalped in January 1847, along with many other American officials and residents. The rebels then marched on Santa Fe, but the American Army responded immediately. A force of more than 300 soldiers from Santa Fe and Albuquerque quickly rode to Taos, and after battles in Santa Cruz and Embudo, the rebels were soundly defeated. The remainder of the Mexicans and Indians took refuge in the San Geronimo Mission Church. The American troops bombarded the church, killing or capturing the insurrectionists and destroying the physical structure. Around 1850, an entirely new mission church was constructed near the west gate of the pueblo wall.

In 1852, Taos and other counties in New Mexico were redefined from an earlier division made in 1846, which was based on an old Mexican government partido, and Taos became the county seat of Taos County.

Taos Valley flourished during this period as other cultures began to enter the territory. Taos was an excellent trade center for the region, but with honest merchants and families came criminals. Before the Civil War, it became a hotbed of many early conspiracies against the American government. After the Civil War, most criminals moved on, and Taos was mainly peaceful. However, there was one significant exception in a notorious character who went by the name of “Colonel” Thomas Means. A surveyor by profession, he arrived in New Mexico Territory shortly after the American civil government was established. He lived in Colfax County for some time and, for years, was closely associated with the tragic episodes that marked the early history of the infamous Maxwell Land Grant. He finally settled down in Taos, where he made life one continuous round of misery for all forced into contact with him. He exhibited an insolence and confrontational disposition that constantly precipitated him into trouble until he became such a nuisance to the more peaceably inclined inhabitants as to render drastic measures necessary. He would not only grossly insult and frequently attack anybody who came within his reach, but he beat his wife so severely on innumerable occasions that her life was in jeopardy.

Finding that their appeals to courts of justice were to no avail, in 1868, several citizens decided to organize that common frontier institution known as a Vigilance Committee and end “Colonel” Means and all his meanness. Though the vigilantes warned him of his inevitable fate if he continued his violent actions, Means ignored the threat. On January 2, 1867, when he drew his knife, fired his pistol at several people, and assaulted and nearly killed his wife following a “big spree,” he was soon arrested. That night, a group of 15-20 heavily armed men “in disguise” entered the room where Means was being held and forcibly removed him from the custody of his guards. The vigilantes then carried him to an adjoining room, which served as the county courthouse, and hanged him from a heavy rafter. The coroner’s jury described Means as “not deserving of the sympathy of anyone, being as he was altogether a dangerous character, continually threatening the lives of peaceable citizens, without distinction and even the lives of members of his own family and innocent children.” The conclusion was that Means had died at the hands of “persons unknown.” The next day, there was general rejoicing that the community had been rid of one of its most disagreeable and dangerous factors. Thus ended the career of one of the most widely known and, at one time, one of the most influential men of northern New Mexico.

The 1880s brought a different type of newcomer to the Taos Valley when gold and rumors of gold, silver, and copper spread throughout the region. In 1866, gold was discovered in Elizabethtown, New Mexico, approximately 30 miles northeast of Taos. In the 1870s, miners began searching for gold in the Red River area. The fever spread, and from 1880 to 1895, the Rio Hondo, which begins high in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains near what is now Taos Ski Valley, was actively searched by placer miners. Mining, however, was not productive in the Taos area.

In 1898, two young artists from the East, Ernest Blumenschein and Bert Phillips, discovered the valley after their wagon broke down north of Taos. They decided to stay, captivated by the area’s beauty. As word of their discovery spread throughout the art community, they were joined by other associates. This marked the beginning of Taos’ history and reputation as a haven for artists.

In 1912, New Mexico became the 47th state in the United States. Three years later, in 1915, the Taos Society of Artists was formed, which unwittingly helped found one of Taos’ leading sources of revenue in the 20th century—the tourist trade. In 1917, Socialite Mabel Dodge Luhan arrived and eventually brought to Taos creative luminaries such as Ansel Adams, Willa Cather, Aldous Huxley, Carl Jung, D.H. Lawrence, Georgia O’Keeffe, Thornton Wilder, and Thomas Wolfe.

On May 9, 1932, the Taos County Courthouse and the other buildings on the north side of the Plaza were destroyed by a series of fires in the early 1930s. This led to the incorporation of the town of Taos on May 7, 1934, and the establishment of a fire department and public water system. That same year, a new Spanish-Pueblo-style courthouse was built with partial funding from the Works Progress Administration. In 1956, Taos Ski Valley was established, bringing increased tourism to the area. Before long, other area ski resorts also emerged nearby – Red River, Sipapu, and Angel Fire.

In 1965, the second-highest suspension bridge in the U.S. highway system was built, spanning the Rio Grande Gorge. While being built, it was called the “bridge to nowhere” because the funding did not exist to continue the road on the other side. However, its magnificence can be seen today along U.S. Highway 64, heading northward to Colorado.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Taos became known as a Hippie community. The city was the perfect place for the 1960s counterculture to express itself, as Taos had long been accustomed to blending cultures. Taos and the rest of New Mexico have long been known for being an artistic and spiritual place. By 1969, at least six communes were established in the Taos area; some sources claim as many as 25. One of the commune’s leaders took to the stage at the Woodstock festival in 1969, inviting all to his commune and the beautiful Taos area — and they came. Although the commune era peaked in the early 1970s, many “old” hippies gradually became part of the Taos community, and their sensibilities remain today.

Unfortunately, on July 4, 2003, the Taos area suffered a fire in the nearby mountains ignited by lightning. The Encebado Fire was within a mile of the historic Taos Pueblo buildings. It took over a thousand firefighters 13 days to contain the 5,400-acre blaze. Fortunately, there was no loss of life or structures, but the Rio Pueblo watershed and the sacred land will take a generation to recover.

Today, Taos is known worldwide by artists, outdoor enthusiasts, and historians. The center of the Taos Downtown Historic District is the Taos Plaza. Just west of that is the Our Lady of Guadalupe Church. The Governor Charles Bent House and the Taos Inn are north of the Taos Plaza. Further north in Taos is the Bernard Beimer House. La Loma Plaza Historic District is on the southwestern edge of the Taos Historic District. East of the plaza on Kit Carson Road is the Kit Carson House and Museum.

Only two miles northeast of Taos, under the shadows of great mountains and occupying both sides of Red Willow Creek, is the pueblo of Taos, with its significant terraced buildings, presenting one of the most primitive illustrations of Indian architecture. It has been occupied for nearly a millennium by the Tiwa Indians, who inhabit a fertile tract of 17,000 acres, granted by the Spanish government. It was originally much larger, but for protection against the Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Ute, who had formerly caused them great annoyance, they gave the eastern part of their grant to Mexican settlers, with the understanding that the latter would assist them in repelling invasions from Taos Canyon. It is the northernmost of the New Mexico pueblos, which, in some places, is five stories high and combines many individual homes with shared walls. There are over 1,900 people in the Taos Pueblo community, though many modern homes are nearby. Approximately 150 people reside at the pueblo year-round. The Taos Pueblo was added as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992.

Ranchos de Taos is located about four miles southwest of Taos. It is situated in the center of fertile agricultural and fruit lands, and it once had several flour mills, schools, and missions.

Taos is now a community overflowing with a long, proud history. It features numerous historic buildings, arts and culture, recreational opportunities, and a population of approximately 6,500 people.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Ancient & Modern Pueblos – Oldest Cities in the U.S.

New Mexico – Land of Enchantment

The Tiwa Tribe – Fighting the Spanish

Pueblo Indians – Oldest Culture in the U.S.

Sources:

Anderson, George B., History of New Mexico: Its Resources and People, Volume 2, Pacific States Publishing Co, 1907

National Park Service

New Mexico Magazine

Snow Mansion

Taos County Historical Society

Taos News

Taos Walking Tour

Tórrez, Robert J., Myth of the Hanging Tree: Stories of Crime and Punishment in Territorial New Mexico, UNM Press, 2008

Wikipedia