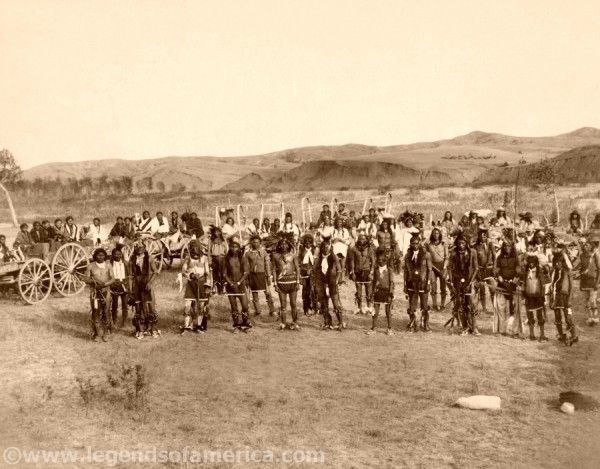

Dances have always been significant in the lives of Native Americans, serving both as a common form of amusement and a solemn duty. Many dances played a vital role in religious rituals and other ceremonies. In contrast, others were performed to ensure the success of hunts, harvests, and other celebrations, as well as to give thanks.

Commonly, dances were held in a large structure or an open field around a fire. The movements of the participants illustrated the purpose of the dance, which included expressing prayer, victory, thanks, mythology, and more. Sometimes a leader was chosen; on others, a specific individual, such as a war leader or medicine man, would lead the dance. Many tribes danced only to the sound of a drum and their voices, while others incorporated bells and rattles. Some dances included solos, while others included songs with a leader and chorus. Participants might include the entire tribe or could be specific to men, women, or families. In addition to public dances, there were also private and semi-public dances that served various purposes, including healing, prayer, initiation, storytelling, and courting.

Dance remains an integral part of Native American culture. The dances are regionally or tribally specific, and the singers usually perform in their native languages. Depending on the dance, visitors are sometimes welcomed, while at other times, the ceremonies are private.

This list of dances is far from all-encompassing, as there were hundreds of dances and variations across the continent.

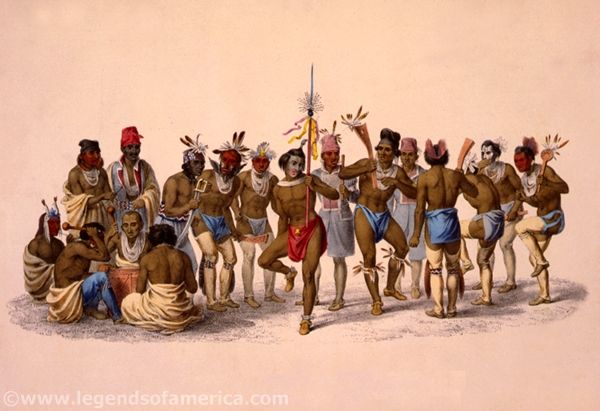

Dancing Associations

There were several semi-religious festivals or ceremonies in which a large number of individuals participated, which were passed down from one tribe to another. One of the best-known examples of Plains Indian culture was the Omaha or Grass Dance, also practiced by the Arapaho, Pawnee, Sioux, Crow, Gros Ventre, Assiniboine, and Blackfeet. Its regalia is thought to have originated with the Pawnee, who taught the dance to the Dakota Sioux in about 1870. The Sioux, in turn, shared it with the Arapaho and Gros Ventre, who taught it to the Blackfeet. Later, the Blackfeet carried the dance to the Salish and Kootenai tribes to the west.

Meetings of these associations were held at night in large circular wooden buildings erected for that purpose. Some of the dancers wore large feather bustles, called crow belts, and a peculiar roached headdress made of hair. A feast of dog’s flesh was often served. Members of some of these associations were often known to have helped the poor and practiced acts of self-denial.

Other dances, such as the Cree Dance, Gourd Dance, and horseback dances, also had associations. However, from tribe to tribe, each had its distinct ceremonies and songs, to which additions were made occasionally.

Fancy Dance

Not a traditional dance of any historical tribe, the Fancy Dance was created by members of the Ponca tribe in the 1920s and 1930s to preserve their culture and traditions. At this time, Native American religious dances were outlawed by the United States and Canadian governments. Traditional dances went “underground” to avoid government detection. However, this dance, loosely based on the traditional War Dance, was considered appropriate for visitors on reservations and at “Wild West” shows. Two young Ponca boys are credited with developing the fast-paced dance that the audience loved. The Ponca Tribe soon built its dance arena in White Eagle, Oklahoma. See the full article HERE.

Ghost Dance – A Promise of Fulfillment

The Ghost Dance (Native American) is a spiritual movement that emerged in the late 1880s, when conditions were particularly challenging on Indian reservations, and Native Americans sought something to give them hope. This movement originated with a Paiute Indian named Wovoka, who claimed to be the messiah sent to earth to prepare the Indians for their salvation. See the full article HERE.

Gourd Dance

Believed to have originated with the Kiowa tribe, gourd dances are often held to coincide with a Pow-Wow, although it has their own unique dance and history. Kiowa legend states that when a man was alone, he heard an unusual song coming from the other side of a hill. Investigating, he found the song came from a red wolf dancing on its hind legs. After listening to more songs through the night, the next morning, the wolf told him to take the songs and dance back to the Kiowa people. The “howl” at the end of each gourd dance song is a tribute to the red wolf. The dance in the Kiowa language is called “Ti-ah pi-ah,” which means “ready to go, ready to die.” The Comanche and Cheyenne also have legends about the gourd dance. The ceremony soon spread to other tribes and societies. See the full article HERE.

Grass Dance

The grass dance, also known as the Omaha dance, is one of the oldest and most widely used dances in Native American culture. This style of modern Native American men’s powwow dancing originated in the warrior societies of the Northern Plains Indians, particularly the Omaha, Ponca, Pawnee, Chippewa, Winnebago, and the Dakota Sioux. The dance is a beautiful, flowing style that reflects warrior movements, such as stalking the game and fighting an enemy. See the full article HERE.

Hoop Dance

Going back centuries, the Hoop Dance is a storytelling dance that incorporates 1-40 hoops to create static and dynamic shapes. These formations represent the movements of various animals and other storytelling elements. In its earliest form, the dance is believed to have been part of a healing ceremony designed to restore balance and harmony in the world. With no beginning or end, the hoop represents the never-ending circle of life. The hoops, typically made of reeds or wood, create symbolic shapes, including butterflies, turtles, eagles, flowers, and snakes. A prominent legend attributes the origin of the Hoop Dance to the Chippewa culture, where an unearthly spirit was said to have been born to live among the people. See the full article HERE.

Hopi Snake Dance

The most widely publicized of Hopi rituals was the Snake Dance, held annually in late August, during which the performers dance with live snakes in their mouths. The dance is believed to have originated as a water ceremony, as snakes were traditionally regarded as the guardians of springs. Today, it is primarily a rain ceremony to honor Hopi ancestors. The tribe regards snakes as their “brothers” and relies on them to carry their prayers for rain to the gods and spirits of their ancestors. See the full article HERE.

Hopi Antelope priests chanting at Kisi Moki snake dance, Image by Detroit Photographic Co., 1902.

Rain Dance

This ceremonial dance is performed by numerous agricultural peoples, especially in the southwestern United States, where summers can be extremely dry. The ceremony was performed to ask the spirits or gods to send rain for the tribes ‘ crops. The dance typically takes place during spring planting and before crops are harvested. However, it was also performed in times when rain was desperately needed. One thing that makes rain dances unique from other ceremonial dances is that both men and women participate in the ceremony. The dance varies from tribe to tribe, each having its unique rituals and costumes. Some tribes wear large headdresses, while others wear masks. See the full article HERE.

Stomp Dance

Performed by various Eastern Woodland tribes, the Stomp Dance is a ceremony that holds both religious and social significance. The term “Stomp Dance” is an English term that refers to the “shuffle and stomp” movements of the dance. In the native Muskogee language, the dance is called Opvnkv Haco, which can mean “drunken,” “crazy,” or “inspirited” dance, referring to the effect the medicine and dance have on the participants. A nighttime event, the dance is affiliated with the Green Corn Ceremony, as practiced by the Muscogee Creek, Cherokee, and other Southeastern Native American tribes. These dances are generally performed several times during the summer to ensure the community’s well-being. Performed by both men and women, these events typically feature 30 or more performances, each sung by a different leader, and may also include other dances, such as the Duck Dance, Friendship Dance, or the Bean Dance. See the full article HERE.

Sun Dance

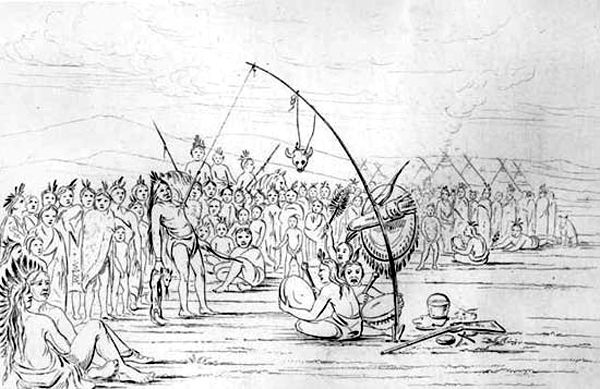

Tribes in the Upper Plains and Rocky Mountain regions primarily practice the Sun Dance. This annual ceremony is typically performed at the summer solstice, with preparations beginning up to a year in advance of the ceremony. Although the dance is practiced differently by various tribes, the Eagle serves as a central symbol, helping to bring body and spirit together in harmony, as does the Buffalo, due to its essential role in Plains Indian food, clothing, and shelter. Many ceremonies share common features, such as specific dances and songs passed down through generations, the use of a traditional drum, prayer with the pipe, offerings, fasting, and occasionally, the ceremonial piercing of the skin. Although not all Sun Dance ceremonies include dancers being ritually pierced, the primary objective of the Sun Dance is to offer personal sacrifice as a prayer for the benefit of one’s family and community.

In the late 1800s, the U.S. government attempted to suppress the Sun Dance. The Cheyenne ceremony “went underground” and reemerged in the twentieth century. In August 1890, rumors of army patrols disrupted the Kiowa Sun Dance, and the dance was abandoned. However, in September of that year, the first Ghost Dance was held, and it remained in place for many years, replacing the Sun Dance. The last Ponca sun dance was held in 1908. The policy of government suppression ended with the issuance of the 1934 circular Indian Religious Freedom and Indian Culture, and since then, Sun Dances have continued to be held intermittently.

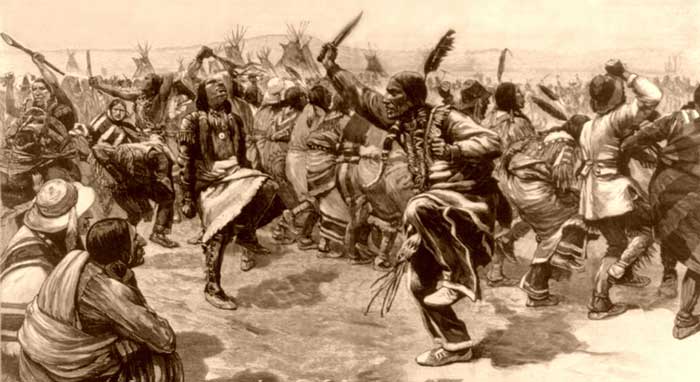

War Dance

Many tribes practiced a War Dance the evening before an attack to observe certain religious rites to ensure success. The warriors took part in a war dance while contemplating retaliation, and the dance stirred emotions, filling the braves with a profound sense of purpose as they prepared for battle. Although the ceremonies varied from one tribe to another, there were common elements among many, including singing that often extended over an entire day and night, interspersed with prayers, the handling of sacred objects or bundles, and occasional dancing. A sweat lodge or other purification ceremony was often held, incense burned, faces might be painted, and a pipe was frequently passed between the participants. Generally, the only musical instruments used in these ceremonies are rattles, drums, and whistles. In the Pacific Northwest, the Pueblos of the Southwest, and the Iroquois of the Woodlands, participants often wore masks to represent various gods or supernatural creatures who acted out parts of the ritual.

War Dance names vary among Indian communities, with the Fancy Dance incorporating war dance rituals of the Kiowa, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Kiowa-Apache tribes. To the Shoshone and Arapaho tribes, the wolf is symbolically linked to a warrior, and the ritual is known as the “Wolf Dance.” The Lakota Sioux Omaha dance is named after the Omaha tribe, which taught the dance to the Lakota. The war dance is known to Utah’s Paiute tribe as the Fancy Bustle, a part of the dancer’s costume.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2025.

Also See:

Native American Photo Galleries

Native American Rituals and Ceremonies

See Sources.