Coming from a respected family that homesteaded near the Satsop River in Washington, John Tornow was born on September 4, 1880. When he was just a small child, he preferred the unexplored wilderness near his home as his playground. As he grew, he spent more time with wild animals than with people.

When the boy was just ten years old, his brother Ed killed his beloved dog, and young John retaliated by killing Ed’s dog. At this time, Tornow began to shun people altogether, vanishing into the woods for weeks at a time.

Hunting only for food, he learned to track as well as any Indian, and his shooting skills quickly became legendary. He would return to his home only for brief visits with his parents, usually bearing gifts of game. By the time he reached his teen years, almost any animal would approach him unafraid, and his family had begun to think he was just a little crazy.

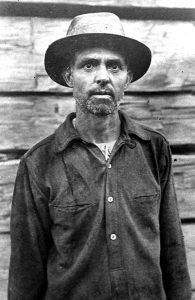

As his brothers entered the logging business, eventually owning their own company, Tornow occasionally worked as a logger but more often continued to maintain his solitary ways in the wilderness. Living off the land, dressing in animal skins, and wearing shoes made of bark, John just wanted to be left alone with nature. Standing 6”4” and weighing nearly 250 pounds, most people thought him a little strange but harmless.

By the first decade of the 20th century, he rarely ventured out of the woods but would occasionally watch the loggers as they worked. On one occasion, he supposedly said to a logger, “I’ll kill anyone who comes after me. These are my woods.”

Convinced he was insane, his brothers captured him and committed him to a sanitarium in 1909. However, the facility, located deep in the heart of Oregon’s wilderness, could not contain the large man, as some 12 months later, he escaped into the forest.

Wynoochee Valley, Washington.

For the next year, John was not seen or heard of until he began to occasionally visit his sister, her husband, and their twin sons, John and Will Bauer. He refused to have anything to do with his brothers, never having forgiven them for committing him to the sanitarium.

Spied occasionally with tangled hair, a long beard, and ragged clothes, his legend grew as people described him as a giant gorilla-like man seen running through the forest. Loggers would say that he appeared to be a large hairy “beast” seemingly appearing out of nowhere before once again vanishing into the forest.

In September 1911, Tornow shot and killed a cow grazing in a clearing by his sister’s small two-room cabin on the Olympic Peninsula. While he was dressing out his kill, a bullet whizzed over his head, and dropping his knife, he lifted his rifle and fired three times in the direction from where the bullet had originated. When he went into the brush, he found his two 19-year-old twin nephews lying dead on the ground.

As to why John and Will Bauer shot at Tornow, it was suggested that the pair thought he was a bear feeding off of one of their herd. However, some historians believe that the boys intentionally made John Tornow their target. Though the truth will always remain a mystery, the mountain man, no doubt, reasoned that someone was trying to capture or kill him when he returned fire. After seeing the dead bodies, Tornow quickly fled the scene, disappearing into the deeply forested Wynoochee Valley. This incident would become the beginning of a legend that would grow large over the next several years and ultimately result in the death of the solitary mountain man.

William and John Bauer.

When the Bauer boys did not return from home, their family contacted Chehalis County (Chehalis County would become Grays Harbor County in 1915) Deputy Sheriff John McKenzie. Soon, the deputy rounded up a group of more than 50 men to search for the brothers, who soon returned with the two dead bodies. Both had been shot in the head and stripped of their weapons.

McKenzie immediately announced that the shooting had to have been committed by John Tornow, and a posse was rounded up to search for the wild man living in the forest. In no time, loggers and farmers making up the posse were roaming the Satsop area and the lower regions of the Wynoochee Valley, wary of the large man they knew to have the intuition of an animal and the skills of an Indian.

The posse was skittish and terrified of the wild man. When one group heard a sound in the brush, a shot rang out, killing a cow. Though the men were sure that Tornow was nearby each time they heard the slightest noise in the woods, they never spotted him.

The longer they searched and didn’t find the “ape-man” killer, the more the tales grew more and more exaggerated. Soon, the stories told of a cold-eyed giant constantly traversing the forest in search of prey, who soon earned such labels as “the Wild Man of the Wynoochee,” “the Cougar Man,” and “a Mad Daniel Boone.” The story grew larger with each telling until the entire countryside was terrified. As the stories spread to the adjacent camps of Aberdeen, Montesano, Elma, and Hoquiam, no one felt safe with John Tornow on the prowl. Women and children were warned to stay indoors as the men oiled their hunting rifles and unleashed their dogs for protection.

As men continued to search into the winter, they were forced into the lowlands due to deep snow. Tornow headed to higher terrain. Sometime later, the wild man broke into Jackson’s Country Grocery Store, intending to help himself to a few provisions. Often, he was known to burglarize cabins and stores to get what he needed to survive. However, on this occasion, he found more than just flour, salt, and matches, but also a strongbox filled with about $15,000. The grocery also served as the town’s bank.

In no time, Chehalis County offered a $1,000 reward for the return of the stolen money, and despite their fears of the “wild man,” the number of men hunting Tornow dramatically increased. The blasts of gunfire could be heard echoing in the forest, and on February 20, 1912, a gunshot-happy hunter killed a 17-year-old boy, mistaking him for Tornow.

The dense area where Tornow made his home is now part of the Olympic National Forest.

A few weeks later, a traveling prospector reported to Sheriff McKenzie that he had spotted Tornow at a camp in Oxbow. Together with Deputy Game Warden Albert V. Elmer, the pair headed out but found only a cold campfire at the point where Tornow had been spied on. Sure that the money was buried somewhere close, the two began to look around. They were rewarded with two gold coins but didn’t find the strongbox.

Sometime later, Sheriff McKenzie and Warden Elmer went missing, and the reward was increased to $2,000. On March 16, Deputy Sheriff A.L. Fitzgerald gathered another posse to hunt for the “ape-man” in both Oxbow and Chehalis Counties. Though they searched high and low for Tornow, what they found instead were the bodies of Sheriff McKenzie and Albert Elmer. Both had been shot between the eyes and gutted with a knife.

Though the searches continued and Tornow was spied on occasionally, the mountain man continued to elude capture. A month later, on April 16, Deputy Giles Quimby and two other men named Louis Blair and Charlie Lathrop came upon a small shack made of bark. Sure that the crude cabin belonged to Tornow, Quimby wanted to head back for a posse, but the other two balked at having to share the bounty.

So, with guns ready, they approached the shack when a shot rang out, hitting Blair, who fell into the nearby bushes. Lathrop returned fire but was immediately hit in the neck, killing him instantly. Quimby was left alone with the marksman and desperately tried to negotiate with Tornow, telling him that all he wanted was the strongbox and promising to let the wanted man go free.

From his hiding place, Tornow shouted, “It’s buried!”

Quimby continued asserting that he wanted nothing but the return of the money and would leave John alone. Though Tornow was hesitant, unsure that Quimby would keep his word, the deputy assured him he would let him go.

Finally, Tornow answered the deputy by stating, “It’s buried in Oxbow, by the boulder that looks like a fish’s fin. Take it and leave me alone!”

Having retrieved the information from Tornow, Quimby didn’t keep his word, opening fire upon the foliage where John was hiding. Though no return shots were fired, Quimby wasn’t sure if he had hit the man or if Tornow might be just “playing dead.” Stealthily, Quimby scurried away through the woods.

When Quimby returned to Montesano, Sheriff Matthews gathered up another posse, and the men began the trek back to the spot where Quimby had fired on Tornow. A ter cautiously approaching the trees, Tornow was found dead leaning against a tree. e men found $6.65 in silver coins on his body, identifying some of them as those taken from Jackson’s Grocery store.

Before Tornow’s body was even returned to Montesano, word had already reached the town that the “wild man” had been killed, and curious gawkers began lining the street to get a peek at the legendary mountain man.

Deputy Sheriff Giles Quimby told newspaper reporters that John Tornow had “the most horrible face I ever saw. The shaggy beard and long hair, out of which gleamed two shining, murderous eyes, haunts me now. I could only see his face as he uncovered himself to fire a shot, and all the hatred that could fire the soul of a human being was evident.”

This further fueled the curiosity seekers’ desire to see the wildman’s face. In response, his brother Fred, who had traveled up from Portland, tried to prevent the body’s public display. However, when some 250 gawkers stormed the tiny morgue demanding to see the body, the overwhelmed coroner allowed them inside. Before it was said and done, the crowd required dozens of deputy sheriffs to prevent the nearly 700 citizens from tearing off bits of the dead man’s clothing and removing locks of his hair.

Fearing that those who could not view the body at the morgue would appear at the funeral, his service was held at the family’s old homestead. Immediately, postcards featuring a photo of Tornow were printed, along with numerous newspaper articles with screaming headlines calling Tornow “The Great Outlaw of Western Washington.”

Of his brother’s death, Fred Tornow would, when questioned by the press, say: “I am glad John is dead. I was the best way now that it is over, and I would rather see him killed outright than linger in a prison cell.”

The Oregonian newspaper noted that at the time of Tornow’s death, he had $1,700 in deposit in a Montesano bank, owned real estate in Aberdeen, and was a part-owner of a timber claim in Chehalis. G les Quimby was proclaimed a hero for finally killing the feared “Wild Man of the Wynoochee,” so much so that he received offers to appear on stage to tell his gruesome tale. Quimby politely turned down these offers.

When the furor of Tornow’s death had settled, Quimby looked for the boulder that looked like a fish’s fin and was delighted when he found it. However, his happiness was short-lived; as search as he might, he never found the strongbox. Numerous other men followed in his footsteps, looking all over Oxbow, Washington, but the $15,000 treasure was never found.

The money is thought to have been buried on the Wynoochee River, where it turns into a large, horseshoe-shaped creek. However, a dam has since been built upstream, which may have caused a change in the river’s flow. Tornow said that he buried the cache near a fin-like rock. The hiding place is within the Olympic National Forest, which requires hunting permission.

Tornow was buried in Matlock Cemetery in Grays Harbor, Washington, where his tombstone stands today.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2025.

Also See:

The Infamous Victor Smith & a Tale of Three Lost Treasures

More Treasures Just Waiting To Be Found

See Sources.