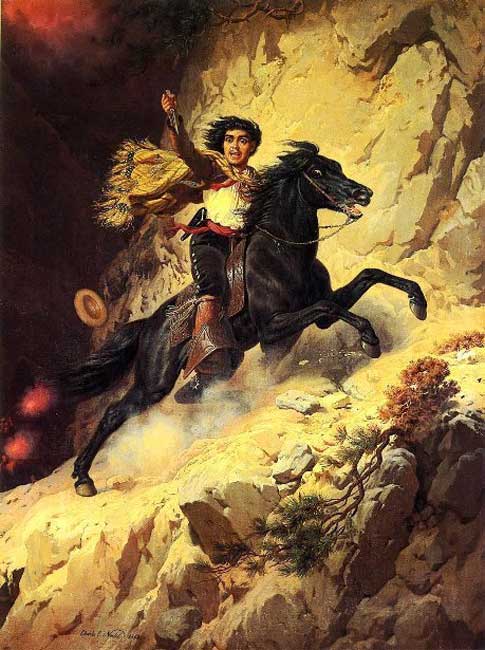

Joaquin Murietta by Charles Christian Nahl.

Depending on a California pioneer’s point of view in the mid-19th century, some described Joaquin Murrieta as a Mexican Patriot. In contrast, others would say he was nothing but a vicious desperado.

Thought to have been born in either Alamos, Sonora, Mexico, or Quillota, Chile, in 1829, Joaquin traveled with his older brother, Carlos, and his wife, Rosita, to California in 1850 to seek his fortune in the goldfields. The three immigrants soon set up a small farm, and the brothers began to work at a claim near Hangtown. However, in the same year as their arrival, a Foreign Miners Tax was imposed in California and their Anglo-Saxon neighbors tried to run them off by telling them that it was illegal for Mexicans to hold a claim. Reportedly, the Murrieta brothers tried to ignore the threats as long as they could until they were finally forced off their claim. Angry and unable to find work, Joaquin turned to a life of crime and other disposed foreign miners, who began to prey upon those who had forced them from their claims.

Murrieta soon became one of the leaders of a band of ruffians called The Five Joaquins, who were said to have been responsible for cattle rustling, robberies, and murders that occurred in the gold rush area of the Sierra Nevadas between 1850 and 1863. Comprised of Joaquin Botellier, Joaquin Carrillo, Joaquin Ocomorenia, and Joaquin Valenzuela, and Murrieta’s right-hand man Manual Garcia, known as “Three-Fingered Jack,” the tales of their crime spree included stealing over 100 horses, making off with more than $100,000 in gold, and killing 19 men.

With posses trailing after them, the bandits were able to avoid the law for several years, killing three lawmen in the process. When travel through the goldfields was made nearly impossible by the Five Joaquins, a bounty was placed on Murrieta’s head for $5,000. Finally, having had enough of the Five Joaquins and the lawlessness in California, Governor John Bigler created the “California Rangers” in May 1853. Former Texas Ranger Harry Love led their first assignment to arrest the Five Joaquins.

On July 25, 1853, the rangers encountered a group of Mexican males near Panoche Pass in San Benito County. In the inevitable gunfight that ensued, two of the Mexicans were killed, one of whom was thought to have been Murrieta, and the other — his right-hand man, Manual Garcia.

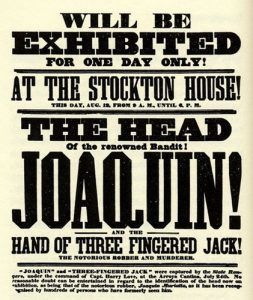

As evidence of the outlaws’ deaths, they cut off Garcia’s hand and Murrieta’s head and preserved them in a jar of brandy. Seventeen people, including a priest, signed affidavits identifying the head as Murrieta’s, and the Rangers involved received the $5,000 reward.

Murrieta’s grisly remains then began to travel throughout California, displayed in Stockton, San Francisco, and the mining camps of Mariposa County, to curious spectators willing to pay $1.00 to see the “sight” of the dead bandit’s head.

But not long after he was killed, speculation began to arise that it had not been Murrieta who had been killed, especially when a young woman, who claimed to be his sister, viewed the head and said that it did not have a characteristic scar that her brother had. Others began to make reports that Marietta was seen in various places in California after his alleged death.

If his legend wasn’t enough during his short lifetime, it would soon grow larger when in 1854, the first “fictionalized” account of his life appeared in a San Francisco newspaper and a book by John Rollin Ridge. In The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murrieta, Ridge portrayed Murrieta as a folk hero who had only turned to a life of crime after a mob of American miners had beaten him severely and left him for dead, hanged his brother, and raped and killed his wife. According to Ridge’s account, Joaquin was a dashing, romantic figure who, swearing to avenge the atrocities committed upon his family, committed his many crimes only to “right” the many injustices against the Mexicans.

According to the tale, Murrieta fled from his claim only to set up a saloon in nearby Hangtown, where miners began to go missing. One by one, the dead bodies of the miners, all who were said to have been part of the killings at the Murrieta claim, turned up with their ears cut off.

After fourteen miners had been found dead or missing, a Hangtown settler identified Murrieta, who fled once again. Before long, he had gathered up his outlaw gang and began to take out his vendetta against the white settlers through robbery and mayhem. However, to his Mexican compatriots, he was generous and kind, giving much of his ill-gotten gains to the poor, who helped shelter him from the law.

There is no evidence that Ridge’s version of the tale is accurate; however, similar atrocities were committed on both Mexicans and Chinese who were living in California at the time.

Over the years, the telling of the tale continued to grow until the dead Mexican outlaw began to be called the Robin Hood of El Dorado and took on a symbolized resistance of the Mexicans to the Anglo-American domination of California. Throughout Gold Country, tales were told of how the outlaw had stayed at this or that hotel, drank in various saloons, and claimed to have met or been robbed by the man.

What happened to Joaquin’s head? It was finally placed behind the bar of the Golden Nugget Saloon in San Francisco until the 1906 earthquake destroyed the building.

The head itself would become part of another legend—the ghost of Joaquin. Even today, the tales continue of Joaquin’s headless ghost riding through the old goldfields, crying like a banshee, “Give me back my head.”

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

Also See:

Outlaw & Scoundrels Photo Gallery

See Sources.